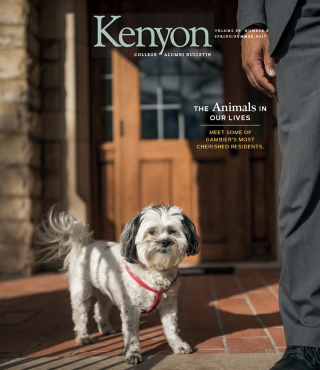

Photo: Julie Barton '95 and her dog, Bunker.

Authors on Animals

A conversation between Laura Hillenbrand '89 H'03 and Julie Barton '95.

Story by Julie Barton '95

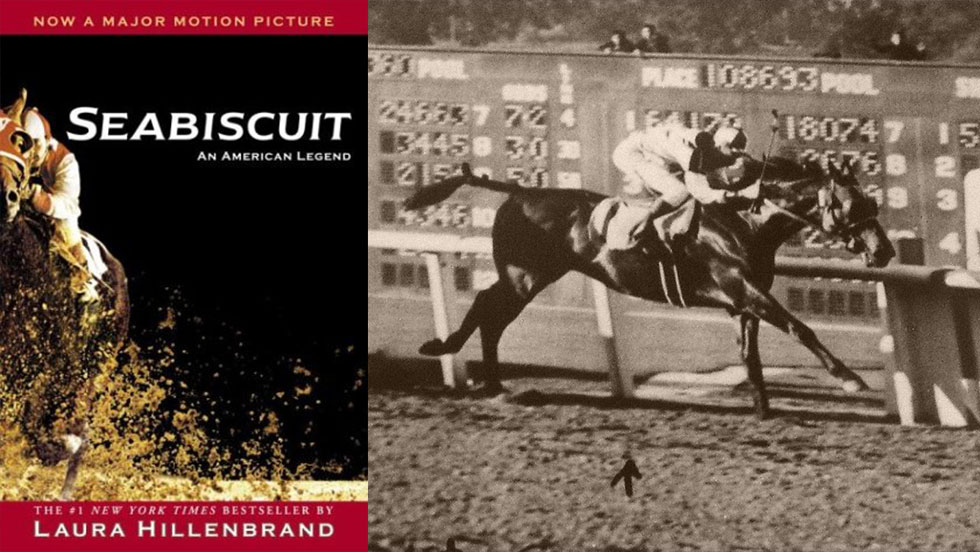

When I think of books about animals, one of the first that comes to mind is “Seabiscuit: An American Legend,” the story of a small, knobby-kneed, nap-loving horse who went on to become a horse-racing phenom. The remarkably written and researched book was a runaway best-seller and a hit movie, and most of us Kenyon grads are quick to claim author Laura Hillenbrand ’89 H'03 as one of our own.

As it turns out, Laura and I have quite a lot in common. We both went to Kenyon. We were both kids who connected deeply with animals. She had horses, dogs, cats, chickens, lizards and more. I was the child whose room reeked of hamsters, guinea pigs, dogs and parakeets.

We both wrote best-selling books about animals. My memoir, “Dog Medicine, How My Dog Saved Me From Myself,” was less a runaway best-seller than a slow-Sunday-jaunt best-seller, but I’ll take it.

We also have both suffered, in different ways, from debilitating illnesses that are invisible to the naked eye. After years of terrible sickness, Laura was finally diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, and she has spent 30 years living with the disease. I was diagnosed at age 22 with major depression. My depression has been chronic and sometimes debilitating, but I do everything I can to stay well, and writing is a big part of my health plan.

So recently, when the Bulletin suggested that I talk with Hillenbrand about animals and writing, I jumped at the opportunity. Here’s a bit of our lovely phone conversation.

JULIE BARTON: So, how do you connect with animals?

LAURA HILLENBRAND: I believe we can have extraordinarily deep connections to animals. Some people just don’t see it. But I do think that they can breathe life into us when nothing else will.

JB: Absolutely. Did you have animals growing up?

LH: Oh, every possible kind. We had a skink. We had a chicken that we raised from an egg. We spent our summers and weekends on my dad’s farm and people from the humane society would leave abused horses there knowing we’d take care of them. Right now, I’m writing my will, and all my benificiaries are animals.

JB: I know you’ve saved several horses from slaughter.

LH: Yes, I once bought five horses in one day that were bound for a slaughterhouse. They all went to good homes.

JB: You mentioned how we both feel deeply connected to animals. When I was a child, I was often told I was too sensitive. No one could prove that our dog was sad — he couldn’t tell us — so how could we know? My depression and your chronic fatigue syndrome are also things that people can’t see. They’re invisible maladies. They’re not broken bones or cancerous tumors. So, some people will say, “Just get out of bed. Why are you so lazy?”

LH: Yeah, they’ll say, “Just cheer up!”

JB: But they can’t see the depths of my sorrow, and they can’t know the extent of your pain or vertigo, for example. I wonder if we feel connected to animals who have no verbal language because we understand what it feels like to not be able to explain or prove something that’s a huge part of ourselves.

LH: That’s a very interesting idea. I’ve never thought of it that way, but I think you’re probably right. Animals address the inarticulate parts of our soul that lie very deep. Animals struggle to communicate with us, and we struggle to communicate with each other. Somehow you can bridge that communication divide with a pet.

JB: I think it’s partly about really slowing down and paying attention to someone else. It’s about listening. Understanding what an animal is communicating can be a revelatory experience.

LH: That is the essential word here: Listening. Everyone who has a beloved pet learns how their pet studies them and understands them. Animals are attentive to us the way very few people are. They read us. They know our moods. It’s one of the reasons we bond to animals so deeply.

Animals are attentive to us the way very few people are. They read us. They know our moods. It’s one of the reasons we bond to animals so deeply."

Laura Hillenbrand '89

JB: Do you find any challenges in writing about animals?

LH: I try to write about animals the way you would write about people, because I think there’s not a lot of difference in the emotional template of animals versus people. To my surprise, when I was promoting “Seabiscuit,” people said, “I never knew animals had personalities until I read your book.” I was astonished. How could they not see it? Animals have perceptions that we’re not capable of. And they’re just so generous. That’s what I always come back to, and it’s probably the deepest motivation I have in saving animals in need. They give us so much and they trust so much. A horse will willingly walk into a slaughterhouse not knowing what you’re going to do to him. That struck me — that you can lead him and you’re betraying him. They are the ones doing the most bending to try to communicate with us. They’re willing to do that. And sometimes they have the capacity to give to us solace when nothing else will.

JB: Do you have any pets now?

LH: Yes, we have two beautiful cats. And I’m considering adopting a horse to bring up here. I went down to Santa Anita for the first time this fall and visited Seabiscuit’s stall. It’s still the double stall where he lived with Pumpkin. I went to see the stall, but I met the horse in it, and it seemed as if Seabiscuit was channeling himself into this horse. This horse was so affectionate to me — and not to anyone else. He was rubbing his lips all over my neck and arm and he wanted to be hugged. I felt this communion with him. I felt responsible for him. It looks like the owner will be willing to give him to me, if I can somehow get him up to Oregon. I am still in not great health and I can’t down-train him from racing. But I’m seriously considering it. Listening to your story makes me want to take him even though it’s kind of a crazy thing for me to do.

JB: That story gives me chills!

LH: So, you think I should do it?

JB: Yes, I absolutely do! It sounds a lot like when I met my dog Bunker. He came up to me, sat down and stared straight into my eyes. He knew he wanted to be with me. I think that horse is waiting for you.

LH: A horse-training friend of mine says that she often sees the horse pick their adopter. This horse’s name is All Around Brown. He’s the son of Kentucky Derby winner Big Brown.

JB: How do you think having a horse would affect your health?

LH: I think it’d be great. I don’t even need to ride him. I could just find a big pasture for him. He could just be somebody’s buddy, and I could go see him every day. It would make me so happy. It’s been 30 years since I got sick. I haven’t had a horse in my life in a long time!

JB: Indeed. I know you’ve said this too, but when I was writing “Dog Medicine,” I thought, “Why am I doing this? This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.” But I remember thinking if I could reach one person, it will have been worth it. Now I get daily emails from readers saying, “Thank you. You gave me hope.”

LH: I get that all the time. I wrote a New Yorker piece (“A Sudden Illness”) 14 years ago and I still get a message or two a week from readers. It took me a year to write. It was awful. I hated doing it. I could hardly write what the vertigo was like. But the piece was distributed to every member of Congress. I think it made a difference. If it does reach somebody or give them a new way to think about their illness, it’s so powerful as a writer.

JB: Tell me about your experience at Kenyon.

LH: Kenyon is a very treasured memory. I came into my own there. I was lost in high school. I was found at Kenyon, and I was sent in the right direction. It shaped me profoundly. I carry Kenyon with me every day of my life.

JB: So do I. Kenyon was like a lighthouse for me. For four wonderful years, I felt nurtured and challenged. I learned to be independent, how to work hard and take my own intellect seriously, and, most importantly, to follow my passion and write.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Also In This Edition

Wild at Heart

Six alumni who work with animals share their favorite tips, tales and tricks of the trade.

Read The StoryPets of Gambier: A Photo Essay

Drama cats. Presidential dogs. A flock of peacocks. Meet some of Kenyon's most beloved residents.

Read The StoryAt the Species Boundary

English professor (and dog lover) Jim Carson probes the significance of animals in literature, drawing on insights…

Read The Story