An Abundance of Awesome

With four best-selling novels, a popular YouTube channel and a cult following, John Green '00 H'16 is ready to…

Read The StoryThe songs change, but Kenyon's deeply rooted singing culture continues to thrive and build bonds - voice to voice, generation to generation.

Story by Kevin Joy

Snapping their fingers, swaying to the beat, the singers of Take Five have the crowd in Rosse Hall under their spell. Doo-wops and ba-daahs swirl around the lyrics in hits from artists as diverse as Nina Simone and Wham! The effect is at once choreographed and casual — just the way the 10 members of the jazz-focused a cappella group like it.

And the Kenyon audience clearly likes it that way, too. Cheers greet every number and every soloist; even the rare flubs and giggles earn hoots of approval.

The hour-long performance on this cold Friday night in November culminates with the Cole Porter standard Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye. It’s a Take Five signature: Since its founding in 2003, the group has used Ev’ry Time as its closer, inviting any Take Five alumni in the audience to join in.

At the end, the singers receive a standing ovation. These are everyday faces on Middle Path: Here, onstage, in the spotlight, they’re stars.

“When you see someone on campus and end up seeing them sing months later, it’s like, ‘Wow, I didn’t know this person could do that,’” said Sam Larson ’17, the musical director for Take Five — who, like many of his a cappella peers, arrived at Kenyon with little prior experience in choirs. “I am absolutely blown away by the sheer amount of vocal talent at this school.”

Singing is alive and well at Kenyon. Vocal groups showcasing a wide range of styles draw enthusiastic audiences. It doesn’t hurt that a cappella has surged in pop culture, from the Pitch Perfect movies to the chart-topping group Pentatonix.

But singing has deep historical roots in Gambier. Going back to after-dinner songs and fraternity bonding rituals, the College’s vocal tradition now embraces 11 extracurricular groups, not to mention the two choirs in which students can earn academic credit — the elite Chamber Singers and the inclusive Community Choir.

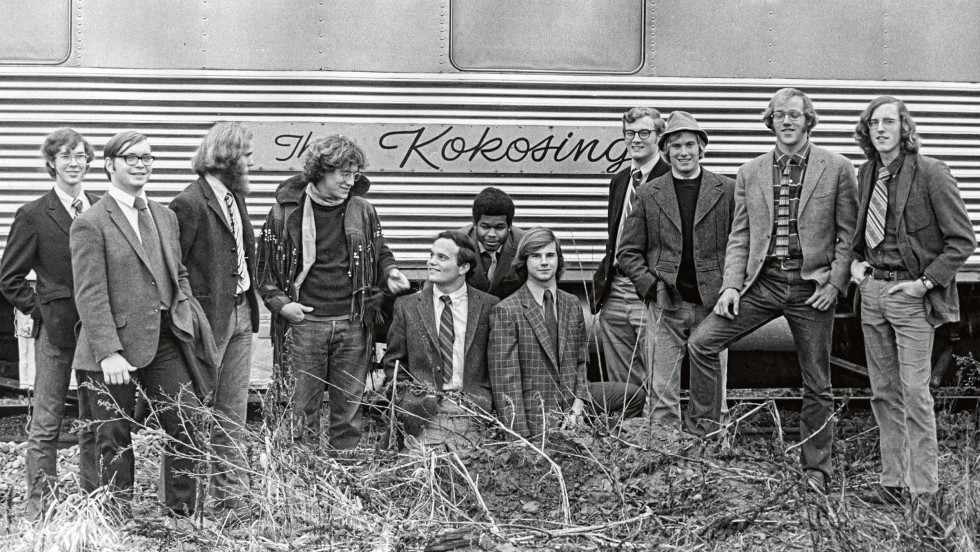

“There’s just something very pleasant about voices singing in harmony,” said Eric Koppert ’74, who organized a 50th-anniversary celebration for the Kokosingers that brought dozens of alumni to Reunion Weekend in May. “The friendships, the joy that you find in working together to achieve something, are at the top of the experience.”

Organized singing at Kenyon took hold early on. After the construction of a common dining hall in 1912, students quickly took up the practice of singing after dinner, especially after the Sunday-afternoon meal. Favorite numbers included “The Weaver’s Song” and “That Old Time Religion” — in the latter, students would insert professors’ names in the lyrics.

Kenyon songbooks already were in existence, having been published in 1859, 1866 and 1908. In the foreword to the 1908 edition, President William Foster Peirce wrote: “Nowhere is singing a more distinctive feature of academic life.”

“This was, for many years, a fairly isolated place where you made your own entertainment,” said Kenyon College historian Tom Stamp ’73. He noted that founder Philander Chase pushed for the purchase of an organ when the fledgling institution “had very little else” to its name.

Older alumni will remember “singing down the Path,” a cordially competitive Tuesday-night ritual in which fraternity brothers would parade from their lodges down Middle Path to the south end of campus, singing as they marched. Greek chapters relied on their own songbooks, supplied by national chapters and often including four-part harmonies. The ritual reached a peak in the 1950s. Although sororities have existed at Kenyon since 1987, the practice never crossed over into sorority life.

Despite singing’s popularity, the College didn’t have a full-time music faculty member until hiring Paul Schwartz in 1947. He established the Music Department and assumed directorship of an existing student choir that recently had gone dormant. Frank Lendrim took over the choir upon his arrival in 1961. The group expanded to include women when Kenyon went co-ed in 1969 and twice traveled to perform in England.

Lendrim’s departure in 1974 led to a series of interim directors and a period of instability. The vocal program fell into disarray, with “many of the best singers giving up on the choir and going to the student groups underground,” according to Professor of Music Benjamin R. Locke, who joined the faculty in 1984.

Locke inherited both the Community Choir — which welcomes faculty and staff singers as well as students, plus community members from outside the College — and the Chamber Singers. He threw himself into reinvigorating the culture of singing at Kenyon. “I did a lot of recruiting,” he said. “That started paying off.”

“Doc” Locke has built the Chamber Singers into a highly accomplished ensemble that tackles an ambitious classical repertoire while embracing various folk traditions — jubilant South African songs are a specialty — and challenging contemporary works. The group rehearses every weekday, and singers memorize their parts. Competition to join the group is stiff: Last year, about 100 students auditioned for 54 spots, and several veterans didn’t make the cut.

Chamber Singers traditions promote camaraderie. Every year begins with Sunday-night lasagna dinners in small groups at Doc’s home. And throughout the year, choir members dress up for “formal Fridays.” A highlight is the annual spring-break tour, a hectic schedule of performances, often in churches in communities with Kenyon connections, with the singers staying in alumni or church-member homes. Back on campus after break, the group reprises its touring concert in a packed Rosse Hall performance.

Web extra: Watch the Chamber Singers perform "The Thrill" in the tower of Peirce Hall.

The Community Choir, numbering 130, sings from sheet music, learning a repertoire that balances ambition with accessibility. Members span a wide range of ages and musical abilities. Some, Locke said, “have never been in a choir before; they don’t need to be scared out of their wits.”

The group gives one concert in the fall, usually joining forces with the Chamber Singers for some works, and one in the spring, when they perform with the Knox County Symphony. They, too, pack Rosse Hall, as the members’ friends, families and colleagues turn out to enjoy the concerts.

The a cappella scene has never been more vibrant.

“Whatever your background, you can find a group,” said Reagan Neviska ’17, a three-year member of the Kenyon College Gospel Choir, whose repertoire ranges from spiritual fare to the Nick Jonas pop hit “Jealous.” She joked that some a cappella acts, depending on their exclusivity and skill level, enjoy “almost a celebrity status” on campus.

Well-established groups include the all-female Owl Creek Singers and the mixed-gender Chasers. Then there are relative newcomers, like the jazz group Take Five, the pop-loving Ransom Notes and the classical female ensemble, Colla Voce.

A more casual group called the Stairwells features acoustic guitar and dancing. The Cornerstones, a Christian group, is believed to have introduced “beat-boxing” to campus in the late 1990s. And the classically focused Männerchor, founded just in 2014, arose spontaneously as a men’s group of “fan boys” to entertain before a Colla Voce show.

Although it has been a point of contention, the Chasers is technically the oldest such group, founded by Lendrim in 1964. Formerly all-male, it went coed shortly after women arrived.

The most recent entrant: the Broken Legs, which first came together last spring, specializing in a cappella renditions of musical-theater selections.

[A cappella groups are] sprouting up like mushrooms on a muggy day in August."

Benjamin Locke, Professor of Music

The boom has left participants struggling to secure stage time. But that’s a good problem to have, maintained Locke. “They’re sprouting up like mushrooms on a muggy day in August,” he said. “And I don’t see it as a competition. The more people sing, the better it is.”

It wasn’t always that way.

Jim Hecox ’69 recalls arriving on the Kenyon campus in 1965 with no options beyond the chamber choir and the Chasers (which included guitar players at the time). He wanted the same kind of experience and aesthetic that he’d enjoyed in an ensemble at the Pingry School in New Jersey, where he had gone to high school.

So, as a first-year, together with several classmates, he founded the Kokosingers — named, of course, for the Kokosing River. The blazer-clad boys sang barbershop standards and dipped into the Yale songbook. Multipart interpretations of Beatles and jazz melodies followed suit.

Still, “there was no venue for a big concert with screaming fans; we sort of informally got together and sang,” Hecox said. “I think people appreciated us.”

The Kokes thrived, soon moving their periodic shows from Peirce Lounge to the main dining hall. By 1973, overflow crowds prompted them to hold their concerts in Rosse Hall.

Even during the counterculture years, marked by anti-war activism, protest songs and anti-establishment styles, the Kokosingers kept their clean-cut looks and sporty blazers while offering up barbershop tunes like Coney Island Baby, recalled reunion organizer Koppert.

“Here were these guys putting on neckties on a campus that didn’t favor ties,” said Koppert, “guys willing to dress up and get up to sing these close harmonies.” He recalled with a chuckle the rare times when he and his fellow Kokosingers would unplug the jukebox in a “rowdy” bar and start singing (usually to favorable reviews from patrons).

Today’s Kokes are as likely to sing fresh hits by Adele and Drake as Kenyon classics like Kokosing Farewell and The Thrill. But the bonds uniting Kokes transcend generational differences. The recent 50th anniversary celebration was just one of many reunions — the group has gathered every four years since 1980. Members past and present often connect during a wintertime East Coast singing tour. Alumni are known for supplying a signature serenade at one another’s weddings.

“It’s a very different bond than you’re used to making,” said Noah Weinman ’16, one of the group’s musical directors. “These will be the people that you love but also get super-annoyed and upset with. It’s more like a team than anything else.”

It’s much the same with the women of the Owl Creek Singers, a group founded in 1975 that now tackles songs by such artists as Tune-Yards and Beyoncé. To build rapport, the group has for years auditioned new members by having them learn by ear the lush song Where Ever You Are (originally sung by R&B artist Terry Ellis of En Vogue). The tune also serves as a closer for their concerts.

As a result, newcomers “just sort of immediately feel like you get to be part of something right away,” said Clara Mooney ’17, vice president of the Owl Creeks. “You’re now connected to tens or hundreds of people who had done this the exact same way for years.”

Web extra: Watch the Owl Creeks perform their traditional closing song, "Where Ever You Are," at their spring 2016 concert.

Kenyon’s 11 a cappella groups make its singing culture arguably more pervasive and intense than elsewhere. There are six a cappella groups at Oberlin College. Brown University, whose undergraduate student body is roughly four times greater than Kenyon’s, has 13.

Gabe Brison-Trezise ’16, a four-year member of the Chasers, said: “I don’t think it’s like this at other schools — here, a cappella concerts outdraw sporting events for the most part.”

“The most important tradition is getting together as a group of friends that can share a love of singing,” said Erich Kurschat ’99, a veteran of both the Chasers and Chamber Singers, who has since provided live backup vocals for A-list artists such as Josh Groban and Usher. “I can’t imagine my life without it.”

There’s a serious side to the a cappella scene.

Gaining entrance to most of the vocal groups has long been fiercely competitive. For any group in a given year, dozens of hopefuls may audition for just one or two open spots.

Ensembles, though, have more recently teamed up to help place hopeful singers with the best fit, noted Jonathan Tazewell ’84 H’15, the Thomas S. Turgeon Professor of Drama and a former Koke.

“In my era, there was a little more competition between those groups; now they seem, at least on the surface, very supportive of each other,” said Tazewell. “They come to each other’s concerts and rehearsals and critique each other to make each other better. I think it’s a much more positive environment.”

The singing is no casual commitment. Most groups practice five days a week, typically after 10 p.m. The demanding schedule ensures not only that members have enough time to learn and perfect complex material but also that they get to know one another on a level that feels more like family.

That makes the artistry far more than a technical endeavor, said Stephen Dowling ’08, who sang with both the Kokosingers and the Chamber Singers. “The goal,” he said, “isn’t to get it right 100 percent of the time; the goal is to mean it 100 percent.”

The music connects, and the connections endure. During the Kokosingers’ January tour, the group performed in the Boston home of a Kenyon alumnus. Several dozen former Kokes were there, and it didn’t take much to get them singing.

“They all got together and started singing songs from their days,” said Weinman. “We really saw ourselves in that — like, maybe that could be us in 20 years, still remembering and reminiscing as a group.”

The Kokosingers perform Drake's "Hotline Bling" at a spring 2016 concert.

From the moment they set foot on campus, Kenyon first-year students are initiated into the culture of song. The gateway: a 60-year tradition known as First-Year Sing.

The rite of passage can be daunting, said Professor of Music Benjamin R. Locke, who joined the faculty in 1984 and took on the job of directing the sing a year later. Still nervous about fitting in, finding friends and choosing classes, the first-years mount the steps of Rosse Hall, face the crowd and sing the songs “Philander Chase,” “Ninety-Nine,” “The Thrill” and “Kokosing Farewell.”

“I remember being terrified… standing in a mass of strangers I had met maybe 16 hours before,” recalled Stephen Dowling ’08. “Thinking about it now, there’s almost a sense that you have to earn a right to sing these songs.”

Making matters worse, at some point upperclassmen turned the performance into a kind of hazing ritual, jeering at the shaky singers and doing their best to drown them out. In a talk about the history of the sing that he gave a few years ago, Locke recalled his first experience with the event. “When we made the trek over to the steps, I felt as though I was leading 400 hobbits to the gates of Mordor. The second I turned my back on the crowd… I was hit by a beer can thrown from somewhere in the middle of the mob.”

By 1989, the boorishness had gotten so bad that administrators decided to cancel the public part of the tradition. The Class of 1993 got wind of the decision and, at their opening dinner in Peirce Hall – when Locke rehearsed them for a non-public sing – they took a stand. Literally: Kelley Wilder ’93 stood up on a table and led her classmates in protesting the cancellation. Locke “joined the revolution” and marched with the class across Ransom Lawn to lead the sing on the Rosse Hall steps.

First-Year Sing has a counter-part – less tumultuous, more poignant – in Senior Sing. As part of Commencement observances, the new graduates climb the Rosse steps again and sing the old songs.

“It really is a flashback moment to where they were four years ago,” Locke said. “Even the most cynical of seniors can be seen wiping tears from their eyes.”

When my wife Jane took me for better or worse, she knew that camp songs were part of the bargain. On long drives, steering with one hand while flamboyantly conducting with the other, I might launch into “I Love to Lie Awake in Bed” (“. . . right after Taps and pull the flaps above my head . . .”) or “Down at the Lake” (“. . . get your little suntan brown at the lake”). Once I got started, I’d run through the whole songbook — for better or worse.

It got to the point where she knew most of the words, and sometimes she’d sing along for a few bars, albeit in a way that struck me as insufficiently enthusiastic. Or, in the middle of a color-war medley or bungalow ballad, she’d stop me with a wince and ask, “You realize that you just changed keys, don’t you?”

I would pretend to take this as a compliment — yes, madame, I can sing in two keys at once — just as I pretended to believe that nobody could resist the joy of this eternally echoing sound track from my boyhood.

I embraced her songs as well, doing my best to learn the two interlacing parts of “Singing Along the Open Road,” from her Girl Scout days, and belting out “En Nacional,” from her year as an exchange student in Argentina. “En Nacional, colegio de mujeres, en Nacional, es lo mejor que hay . . .” I have minimal Spanish, but I loved to wrap my tongue around this school ditty — yes, partly because the lyrics took a naughty turn, but also because of the inherent playfulness of the song, of all song, really, music caressing or cavorting with its perfect partner, language.

From lullabies to TV jingles, songs latch onto us, and hold on. I found myself thinking about this uncanny power when I read “Sing Along,” our story about the tradition and culture of singing at Kenyon. The old fraternity marching songs, the modern proliferation of a cappella groups, ageless “Doc” Locke and his Chamber Singers and Community Choir, First-Year Sing and Senior Sing as bonding rituals and rites of passage: The story makes it clear that, on this campus, song is a way to belong.

In song, we’re all obedient to some strange spell. We evolved into singing — the tuneful ape, who turned hoots and huffs into 32-bar standards. Whales may vocalize, but I doubt that golden oldies get stuck in their heads.

Jane and I came to Gambier in 1989, when she got a job teaching French. I was the trailing spouse, alone in a draughty rental house at the bottom of the Hill, without work, office, colleagues, niche. But, Kenyon being Kenyon, I heard about the Community Choir, and I sought out Ben Locke to see if I could join.

“What part do you sing?” he asked me.

I had no idea.

“Based on the timbre of your voice, I’d say you were a tenor.”

I was pleased to learn that my voice had a timbre, and a little puffed up about the fact that I shared a range with Pavarotti. In rehearsals, however, I soon discovered that my best hope of avoiding chromatic drift as we struggled through the Mozart Requiem was to stand close to English professor John Ward and try to match his pitch.

Around the house, the Requiem’s “Confutatis” replaced “Down at the Lake.” But if the lyrics carried more weight (Confutatis maledictis … “when the accursed are confounded”), the personal meaning was much the same. Song initiated me into a place, drew me into a kind of family.

I eventually found a fuller and more suitable niche, with a job writing and editing in the Communications Office and a chair in the trumpet section of the Symphonic Wind Ensemble; later, the Jazz Ensemble as well. In short, my life at Kenyon has been a good marriage of words and music.

I don’t sing as much as I used to, but the trumpet — transmuting air into melody — has its own uncanny power, and its own capacity to annoy. When I’m practicing, Jane will sometimes glance up from her work and give me a look. I’m all too familiar with that . . . let’s see . . . indulgent smile? Affectionate grimace?

I’ll stop and turn to her hopefully.

She’ll say: “That’s loud.”

— Dan Laskin

With four best-selling novels, a popular YouTube channel and a cult following, John Green '00 H'16 is ready to…

Read The StoryAs record numbers of students seek psychological help, Kenyon's counseling center expands its reach.

Read The Story