The Architect

Looking back at the work and legacy of Graham Gund ’63 H’81, who died in June.

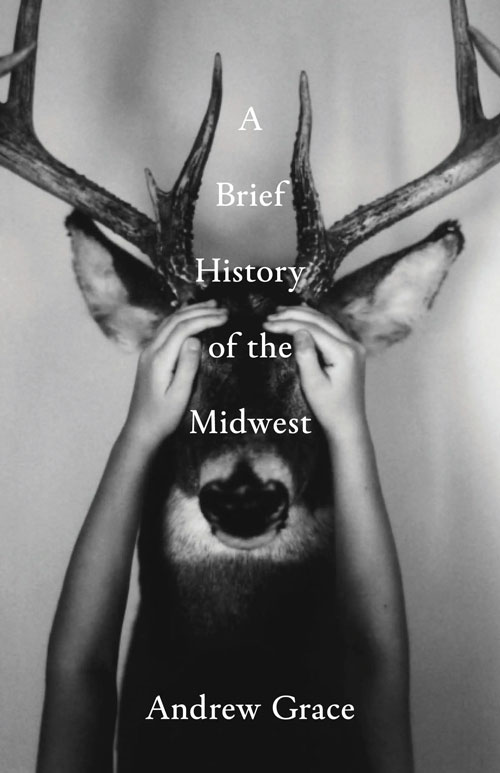

Read The StoryAndrew Grace ’01 reflects on the inspiration behind his new poetry collection.

Thistle grows all over the fields and ditches of Knox County, where I live. Yet it has held cultural and even medicinal significance for centuries, from Pliny to the Vikings to ancient Scottish iconography. Today in agriculture, thistle is categorized as a weed and is sprayed with herbicides in an attempt to eradicate it. But weeds are adaptable and prolific and they find ways to endure and even thrive, outwitting newfangled chemical strategies that have deemed them undesirable. Many human lives are lived this way. In “A Brief History of the Midwest” (Black Lawrence Press, 2025), my hope was that, by making the first line of the first poem — which is also the title poem — give primacy to thistle and argue that one can understand history through its lens, I would be centering something marginalized and showing its power.

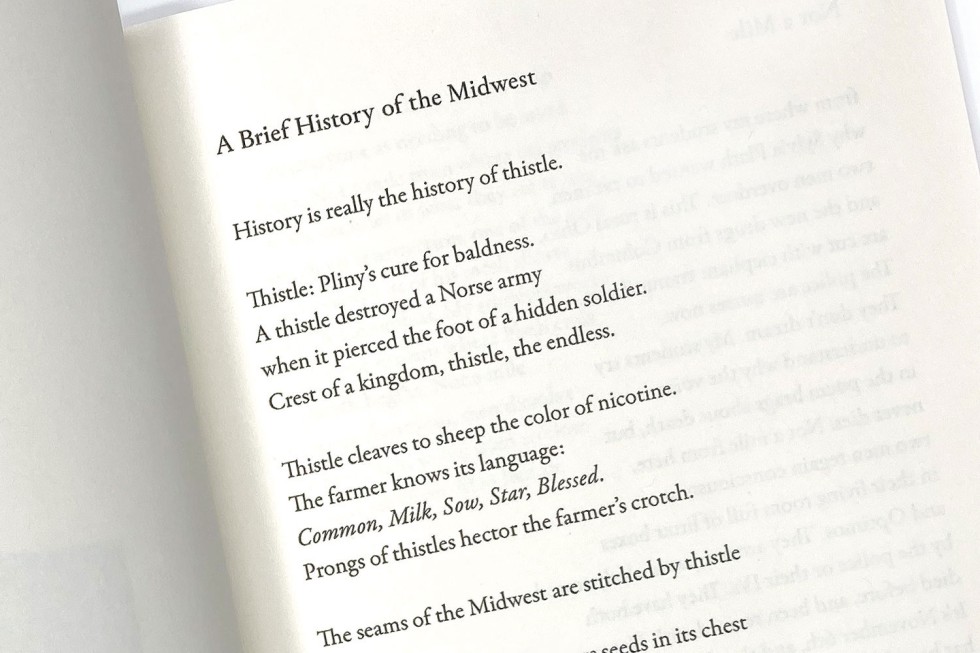

History is really the history of thistle.

This is the first poem in the book. I wanted to start with an emphasis on resilience, which is why I chose thistle — one of my favorite weeds.

Thistle: Pliny’s cure for baldness.

Pliny the Elder was a Roman military leader and author, and his 37-volume “Natural History” is the largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire. Pliny also thought that thistle was a remedy for bad breath and flatulence.

A thistle destroyed a Norse army

when it pierced the foot of a hidden soldier.

Crest of a kingdom, thistle, the endless.

Thistle cleaves to sheep the color of nicotine.

The farmer knows its language:

Common, Milk, Sow, Star, Blessed.

Prongs of thistles hector the farmer’s crotch.

I grew up on Shadeland Farm in east-central Illinois, and one of our summer chores was to “walk beans” — fanning out in the soybean fields to to get ride of weeds. either by pulling them or cutting them with a hook. Thistles were always the worst to deal with because of their sharp thorns and deep roots.

The seams of the Midwest are stitched by thistle

and a field of thistle hoards its seeds in its chest

until thistledown and finch grift its clutch.

Its morning blossoms are pink as raw salt.

They are shorn and gathered into a pile to burn.

Seeds will spread, borne on carbon to new radii.

Thus the next acreage taken by its thorns.

I wanted to give primacy to thistle, centering something that has been marginalized and showing its power.

Thistle and ditch become synonymous.

The hill lay down their shadows like Tarot cards.

I like this line, but I have the feeling that I stole it from someone and have forgotten whom.

The history of the Midwest is written in thorn.

When I first came to Kenyon as a student in 1997, it was the first time I realized that there were different Midwests. Ohio farms were smaller and more ramshackle than Illinois farms, which I liked. And many of my classmates from the coasts found the Midwest exotic! In m y first poetry workshop, I was sheepish to turn in my poems about harvests, grain elevators and anhydrous ammonia because I assumed everyone know about that stuff and would find it boring, but most of my classmates had no idea what I was talking about.

Andrew Grace ’01 is a poet and assistant professor of English at Kenyon. He is the author of three poetry collections, with work appearing in The New Yorker, Poetry and Boston Review. He also serves as a senior editor at the Kenyon Review. Learn more at andrewpgrace.com.

About Annotated: Members of the Kenyon community create books, poems, magazine articles, songs, plays, screenplays and much more. Here, writers annotate their work, line by line.

Looking back at the work and legacy of Graham Gund ’63 H’81, who died in June.

Read The Story24 ways to reconnect, stay engaged and make the most of your Kenyon community.

Read The StoryMeet the alumni entrepreneurs, makers and innovators reshaping the food business.

Read The Story