Quest for Justice

At the pinnacle of a decades-long career in the Foreign Service, Ambassador Bridget Brink ’91 relies on lessons…

Read The StoryA free-flowing conversation between David Lynn ’76 and Marc Millon ’77.

My good friend Marc Millon ’77 and I attended Kenyon at the same time, but somehow our paths never crossed when we were students. My senior year was his junior, and he was a member of the very first group to go on the Kenyon-Exeter Program to Devon, led by Professor Gerald Duff. During that year, he met his wife, Kim, a talented artist and photographer, and he returned to the UK to marry her after graduating. He’s lived in Topsham, Devon, ever since.

Coincidentally, I moved to Exeter on my own in 1976, his senior year, to write and to live near Professors John and Maryanne Ward, who were running the Kenyon program that year. But it wasn’t until 1992, when Wendy Singer and I led the program and were living in Professor Galbraith Crump’s house in Topsham, that Marc and I finally met. More than three decades of friendship — and many shared bottles of wine — later, I called up Marc to reminisce and talk in-depth about his latest book, “Italy in a Wine Glass: The Story of Italy Through Its Wines” (Melville House 2024). What follows is a condensed version of our free-flowing conversation.

MM: By the time you and I finally met, some 15 years after I had graduated, we had each moved in completely different directions to arrive back in the same place. Kim and I had embarked on our career writing and photographing books about wine, food and travel. By 1992, we had already published seven books and had just been commissioned to write and photograph our next two-book project to celebrate the opening of the Channel Tunnel that would link the UK to Europe.

DL: Among those many other projects, you wrote and photographed a series of award-winning books in the 1980s and ’90s, “The Wine Roads of France,” “The Wine Roads of Italy” and “The Wine Roads of Spain.” Not only were these commercially successful, they launched a whole new way of appreciating wine in terms of local foods and traditions, building on the notion of terroir, and going far beyond that.

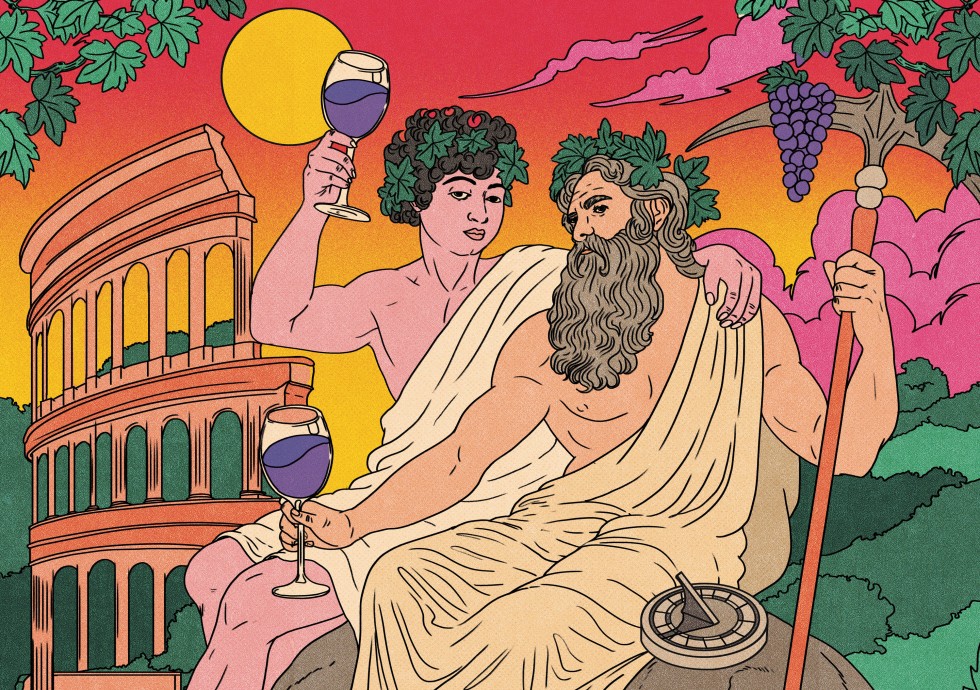

But now you’ve gone in another innovative direction in your new book, “Italy in a Wine Glass: The Story of Italy Through Its Wines.” Rather than seeking a single, coherent narrative, it creates a great quilt of Italian history — and the origin and originality of its wines — through stories that trace back to the Greeks and the Etruscans, their grapes and their methods of winemaking. Many of those methods, you show, are still being employed or have been rediscovered today. And the stories burst with dramatic detail. Can you talk about your love for Italy and its wines, and how you came to structure this book through stories?

MM: “Italy in a Wine Glass” had a very long gestation, maybe around 30 years or so, while Kim and I were researching, writing and photographing “The Wine Roads of Italy.” We kept coming across wines that had such compelling stories linked to history, from antiquity to yesterday, today and tomorrow: a wine from a vineyard replanted in Pompeii following the exact Roman training system that had been in place until that fateful day in 79 CE when life was obliterated; a villa and wine estate given by Italy’s first king Vittorio Emanuele II to his mistress Rosa Vercellana, still producing great wines today; wines from cooperative wineries founded more than a century ago on social ideals that are still strongly adhered to today; wines made from vineyards grown on lands confiscated from convicted Mafiosi; a wine from grapes grown on Europe’s only remaining island penitentiary, Gorgona, the production of which serves to assist in the rehabilitation of some of the country’s most hardened criminals; and many more such instances that you’ll find in the book.

History has always been a love and fascination of mine. In fact, I started at Kenyon with the intention of being a history major, and one of the most rewarding classes I took (it must have been my sophomore year) was Medieval History with Professor Robert Baker. We were both there in something of a golden age, or so it felt to me, with giants in the English department such as Galbraith Crump, Perry Lentz, Fred Turner, Gerald Duff, Gerrit Roelofs, John Ward. They were all brilliant in their own ways and fields and, thinking back on it, they all must have been quite young, maybe just in their 30s, and they all loved literature and above all teaching literature. Robert Daniel was older, something of the father of the department, and it was he who especially encouraged me to write. So I decided to major in English instead of history, and that allowed me to participate on the inaugural year of the Kenyon-Exeter program. It was at Exeter that I met Kim, a first-year student at the university, who was reading English and fine art. Together we soon discovered our shared interest and love for wine.

DL: I’m particularly fond, naturally, of your description in “Dante Alighieri,” Chapter 12 of “Italy in a Wine Glass,” of the evening of outstanding food and wine we shared with the Kenyon travel group we were leading in the Foresteria of the Villa Serègo Alighieri outside of Verona. This estate was bought by the son of the great Italian poet in the 14th century, and remains in the family, producing some of the great wines of Valpolicella. The dinner was long, elegant and joyful, and we chanced upon the current Conte Pieralvise Serègo Alighieri standing in the shadows, elegantly suited, and ensuring that every detail of the meal was seen to. At our behest, he repaired with us to the library, with its high bookshelves and sconces in the walls, each of us with a glass of incredible wine in hand. To the astonishment of his own staff — they swore he never did such a thing — he bowed and recited the opening 50 lines or so of his ancestor’s masterpiece. I still get chills thinking about it.

MM: Yeah, me too! That was a moment that I will never forget, an extraordinary occurrence when literature, history and wine all came together through the beauty and power of that very special Casal dei Ronchi Recioto.

Perhaps it was my liberal arts education at Kenyon that has led me to approach wine — and especially Italian wine — as I do, for it is an infinitely fascinating subject that can bring together literature, art, religion, sociology, economics and political science, all topics covered in my book in one way or another. Chapter 1 begins with Homer’s “Odyssey;” Roman poets praise and extol famous wines such as Falernum; Dante of course and Boccaccio, too. Wine was a subject of classical and Renaissance art. Wine played an important part and continues to have a role in religion, the triumph of Christianity, the monastic tradition, pilgrims and wine along the Via Francigena.

Wine is a reflection of society, too, with systems of land tenure not only shaping the landscape itself but reflecting the styles and types of wines produced. The cooperative movement is another important example. Italy’s economic miracle led to the industrialization of Italian wine, but real quality and economic as well as critical value was only achieved when wine producers reclaimed that ancient patrimony of greatness with the rise of the so-called designer and Super Tuscan wines. And political events are reflected as well, with the influences from foreign occupiers such as the Austrians in Northeast Italy and the Spanish in the South, Sicily and Sardinia all had a profound influence on styles and types of wines produced, such as Gewürztraminer and Kerner from Sudtirol to Tintilia in Molise and Vernaccia di Oristano (a unique sherry-type wine) from Sardinia.

DL: So many wines to taste, so many stories to tell. I look forward to sitting over a bottle of something lovely with you, perhaps Mario’s Barbera D’Alba, which is in the book, of course!

At the pinnacle of a decades-long career in the Foreign Service, Ambassador Bridget Brink ’91 relies on lessons…

Read The StoryExamining the impact — and work left to do — after the record-breaking Our Path Forward to the Bicentennial…

Read The StoryA front-row seat to learn from fellow alumni what it was like to be in their shoes for some unforgettable experiences…

Read The Story