Preserving Our Place

How the Philander Chase Conservancy is protecting Kenyon’s rural setting, one farm at a time.

Read The StoryIn a freewheelin’ conversation, Jay Cocks ’66 H’04 talks with Chris Eigeman ’87 about his Oscar-nominated film, “A Complete Unknown.”

Story by Chris Eigeman ’87 | Photography by Benjamin Norman

On Nov. 6, 1964, Jay Cocks ’66 H’04, a Kenyon sophomore, and David F. Banks ’65 H’01 P’96, a junior, drove from Gambier to the Columbus, Ohio, airport to pick up a young folk singer they had booked for a gig at Kenyon. The students were responsible for getting the rising star to and from campus and ensuring that he and his crew had everything they needed during their stay.

“Wearing high-heel boots, a tailored pea-jacket without lapels, pegged dungarees of a kind of buffed azure, large sunglasses with squared edges, his dark, curly hair standing straight up on top and spilling over the upturned collar of his soiled white shirt, … Bob Dylan came into the terminal taking long strides, walking hard on his heels and swaggering just a little,” Cocks later wrote in a sprawling Collegian cover story titled “A Day with Bob Dylan.”

For Cocks, it was an unforgettable first impression of a man who would not only change his life but also reshape the musical landscape. Cocks’ epic day with Dylan — during which he interviewed him over takeout in a Mount Vernon motel, tracked down the best local wine and fended off eager fans after Dylan’s packed concert in Rosse Hall — became so ingrained in Dylan lore that it was reprinted in Jonathan Cott’s 2006 book, “Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews.” A review in The New Yorker described the chapter as “a precociously observant report by Jay Cocks, for a campus publication, on Dylan’s visit to Kenyon.”

After Kenyon, Cocks worked as a film critic for Time and other publications before transitioning into screenwriting. He co-wrote “The Age of Innocence” (1993) with Martin Scorsese, earning an Oscar nomination for best adapted screenplay, and went on to collaborate with Scorsese on “Gangs of New York” (2002), for which he received a second Oscar nomination, and “Silence” (2016).

In a 2003 Kenyon Alumni Magazine interview, Cocks credited Kenyon and his Collegian story with kick-starting his career, noting that Kenyon “would allow you a fair amount of latitude to make your own world, to make your own school. There aren’t enough good movies around? OK, here’s the Kenyon Film Society. No film festivals? Start one. Crummy music? Bring Bob Dylan and Nina Simone to campus.”

At the Dylan concert, he recalled, “You knew you were in the presence of something and someone who changed the definition of special. I wrote it all up in the Collegian, and it was a good calling card. It got me my gig at Time.”

Now 80, Cocks is back in the spotlight — and was nominated for another best adapted screenplay Oscar — for co-writing “A Complete Unknown,” a film about Dylan’s early years, directed by James Mangold. Set in the early 1960s (around the same time that Cocks first met Dylan), the film draws from Elijah Wald’s 2015 book “Dylan Goes Electric!”

Two weeks after the 2025 Oscar nominations were announced, actor and filmmaker Chris Eigeman ’87 joined Cocks for lunch at a cozy Italian restaurant on New York City’s Upper East Side. Eigeman is best known for starring in Whit Stillman’s “Metropolitan” and “The Last Days of Disco,” as well as Noah Baumbach’s “Kicking and Screaming” and “Maid in Manhattan.” He also appeared in television series like “Gilmore Girls,” “Malcolm in the Middle” and “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” and wrote and directed the films “Turn the River” (2007) and “Seven in Heaven” (2018).

Over plates of pizza and chicken parmesan, they talked about Dylan, Kenyon, the making of “A Complete Unknown” and the enduring power of great storytelling. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

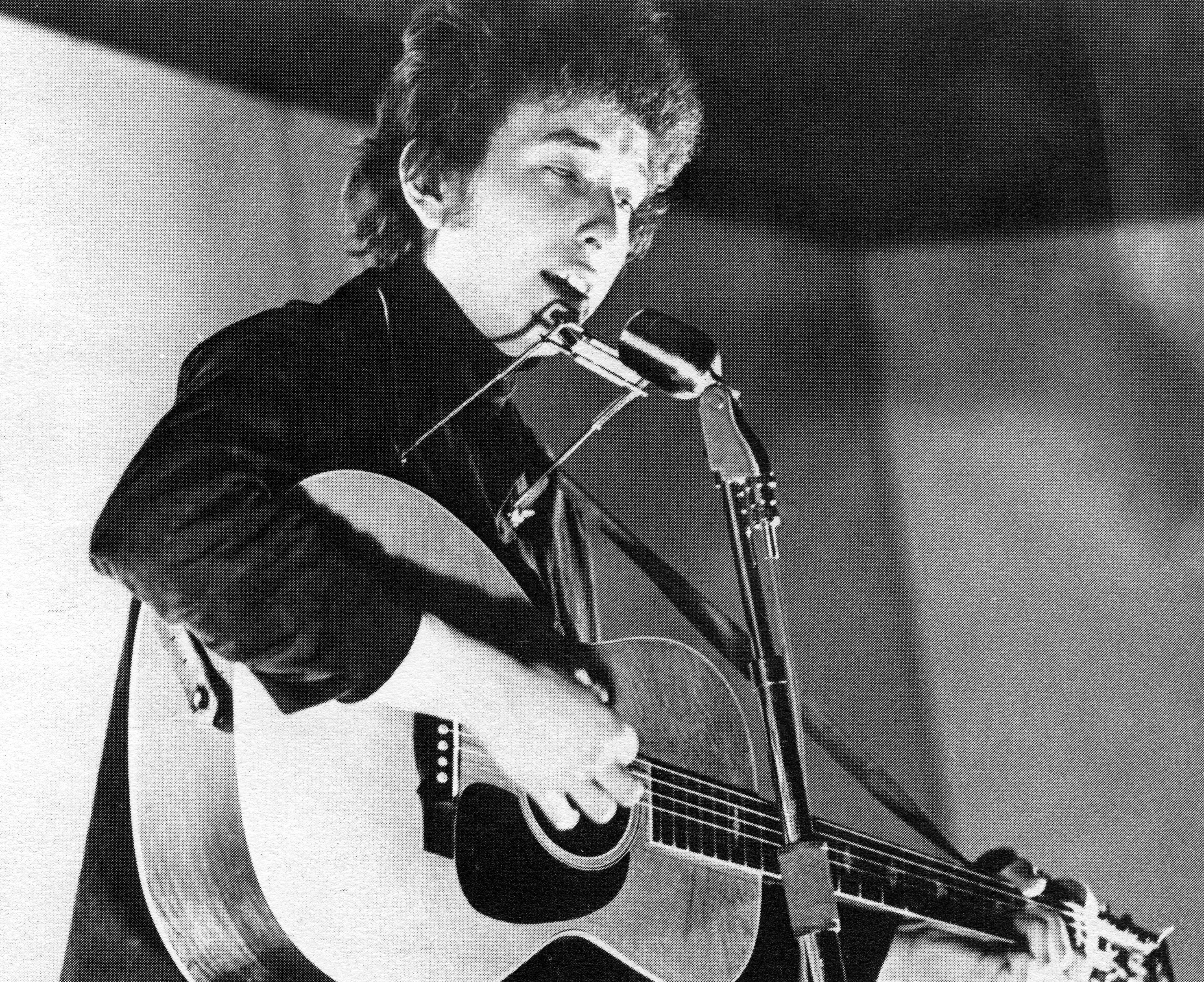

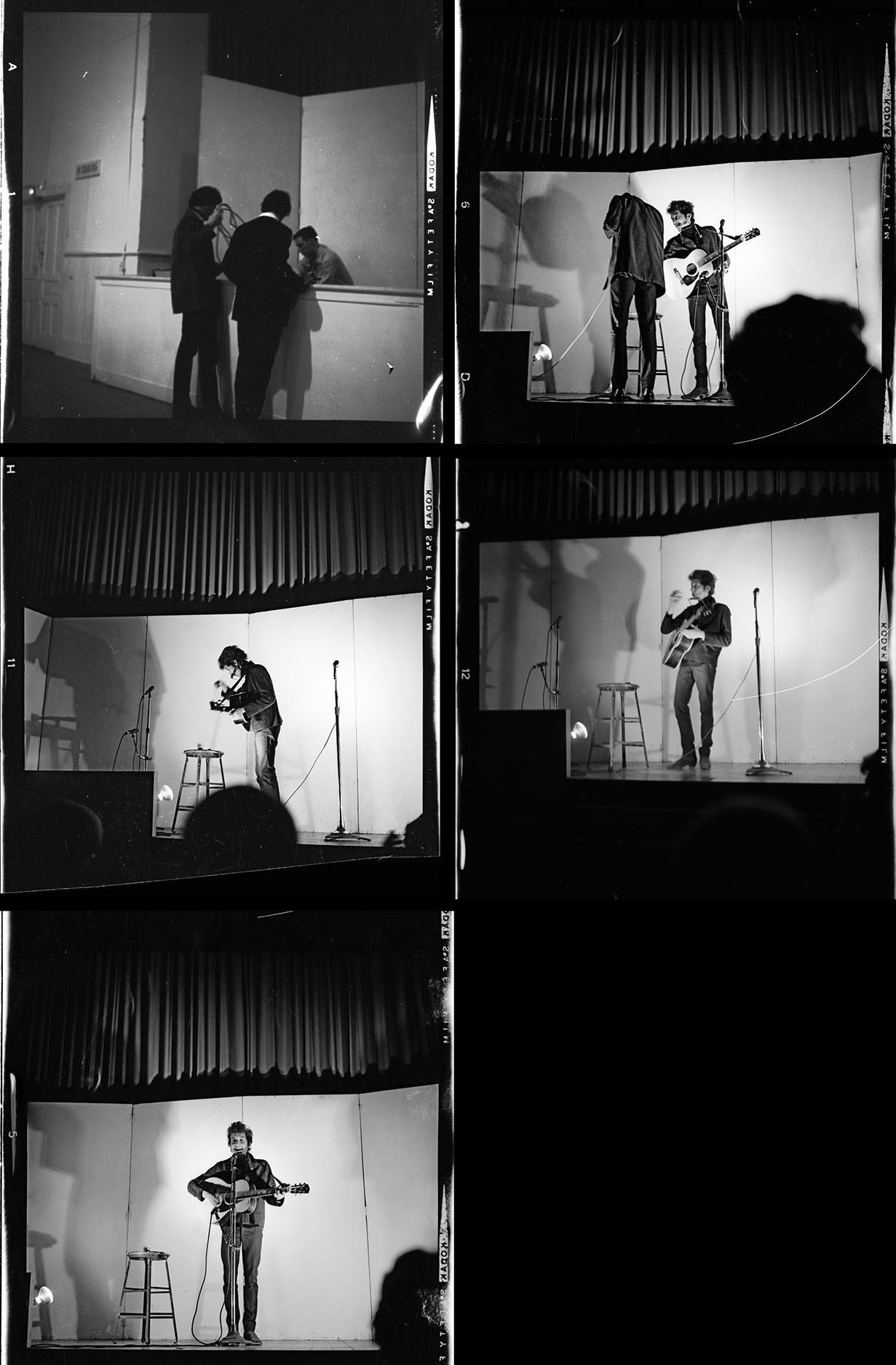

Bob Dylan performing on the Rosse Hall stage in 1964.

Bob thought it was pretty funny that Rosse Hall was next to the graveyard.”

—Jay Cocks ’66 H’04

Chris Eigeman: Let’s start at the beginning, when you picked up Bob Dylan at the Columbus airport in 1964.

Jay Cocks: All right.

CE: How did that come about? I mean, how do you book Bob Dylan into Rosse Hall?

JC: OK, you gotta understand that there was kind of a folk circuit at that time where you could book folk singers, or musicians who would play the college circuit. It was a good way to pick up money — lots of traveling, but it wasn’t clubs. And we had something at Kenyon at the time called the entertainment committee, which was just two people — me and my dear friend David Banks. We booked Josh White, Jesse Fuller, Nina Simone — and Bob.

CE: That’s a kind of a murderer’s row. Interestingly, 1963 and 1964 are right in the crosshairs of your movie, “A Complete Unknown,” in terms of timing. Dylan’s eponymous album was already out. Then “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” came out, and “Another Side of Bob Dylan.”

JC: Yes. So, David and I go in this little Volkswagen Beetle to pick up Bob and his road manager, Victor (Maymudes) from the airport. They’re in the back seat, we’re all squished together, and we’re talking. It took me decades to realize that at that time, Bob was only two or three years older than I was, and he was already Bob Dylan. And I’m this kid in the back. I say to him, “You know, I write for the college newspaper. Is it OK if I write about this?” He says, “Sure.” And he is very friendly but doesn’t give a lot of himself. I’m not expecting him to give away a part of himself, but he is very congenial, and we laugh, more like contemporaries. A non-musician relating to musicians is always a little bit different. You know the vocabulary, but you don’t speak the language.

CE: You can’t get fully behind the curtain.

JC: Right.

CE: You finally get him up to campus, and he looks around and he says, “Wow, great place for a school! Man, if I went here I’d be out in the woods all day gettin’ drunk. Get me a chick and settle down, raise some kids.” I have no idea why Kenyon doesn’t emboss that on every letterhead.

JC: Bob thought it was pretty funny that Rosse Hall was next to the graveyard.

CE: I’m picturing him having to scamper through the graveyard to avoid fans.

JC: I had another friend from Kenyon, Terry Robbins (’68). He founded the Ohio Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) on campus, and I believe he was the only member. He would sit in the middle of Middle Path, protesting on behalf of Martin Luther King Jr., and people laughed at him. He was a great guy but he got too radical for the SDS and helped form the Weathermen, and he named them. “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

CE: They got their name from the Dylan song.

JC: Right. Several years later, Terry was in New York, in the Village. This would’ve been after Bob’s 1966 motorcycle accident. He saw Bob on the street, went up to him, and Bob was OK about it. And Terry said, uh, “Excuse me, uh, I just wanna say, you know, I saw you at Kenyon College.” And Bob went, “Oh, you mean that place with the graveyard?” (laughter)

I was lucky to see Bob close up in Rosse Hall. He had his two friends come through for the concert: John Byrne Cooke and Bobby Neuwirth, who’s played by Will Harrison in the movie. Anyway, Bob comes on stage; everybody loves him. It’s standing room only, so I’m standing over on the side with Bob Neuwirth and John Byrne Cook. And Bobby (Dylan) gestures to me, and he says, “Listen to these, these songs haven’t come out yet.” And in succession, Bob sings “Gates of Eden,” “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” and “Mr. Tambourine Man.” One. Two. Three. Who could forget that?

CE: Did you stay in touch with Dylan?

JC: I’ve seen him over the years a number of times. But we mostly stay in touch through Jeff Rosen, my great friend, who’s his manager.

CE: One of my favorite moments in the film is right at the jump. I don’t think we’re five minutes into it when he finds his way to Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, and he wants to play for Woody, and sort of struggles with his guitar. And Pete Seeger says, “What, are you shy?” And then Bob says, almost to himself, “Not usually.” (laughter)

The best thing about it to me was, first of all, this notion that Bob Dylan is an absolute cipher and nobody can figure him out is completely taken off the table. Bob Dylan knows who he is, and then you will figure that out by watching him. And he has a sense of humor even about himself.

JC: Incredible. Are you familiar with Native American art? You know the Northwest Coast masks?

CE: Yeah. I know the totems a little bit.

JC: So, you open up the mask, and there’s another mask inside.

CE: Right.

JC: That’s Bob. And the title of the movie, (director and co-writer) James Mangold changed it. My title was “Going Electric.” His title turns out to be maybe not quite as poetic, but more apropos.

CE: It’s a good title.

JC: Yeah.

CE: In many of your scripts, I find there are little pieces of, like, metaphorical knitting that are revelatory. I remember when Dylan and Sylvie are having essentially their first fight when she’s going to leave for Europe, and Dylan is sitting on the bed, noodling around with like the first eight bars of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” and the music is saying — “pay attention.”

JC: Yeah. I love laying music into stuff. I’m always laying music into stuff that I write. Meeting Bob and spending time with Bob was a life-changer, but you don’t have to know him personally to get that same effect because his music is so intimate. He’s not, but the songs are. They seem to be mysterious. They can be abstruse. Sometimes you don’t know where they’re coming from or what they’re about, but you kind of do.

Here’s what I tell people: There are no inaccuracies in this movie. There are only choices.”

—Jay Cocks ’66 H’04, on “A Complete Unknown”

CE: There’s this heart punch in the movie where Bob’s in the elevator and he’s talking to his then-date, and he says, “They all ask me where these songs come from. And that’s not what they’re asking. They’re asking, ‘Why didn’t those songs come to me?’ ”

JC: It sounds pretentious trying to define Bob’s place and influence and it’s just out of sight. He deserves his (2016 Nobel Prize in Literature). He deserves everything, as far as I’m concerned. Nobody could write like him or sing like him. And when you turned on the radio, it was like hearing William Blake sing to you. You know? What he did was unprecedented.

CE: The casting of the movie is also amazing. I mean, obviously Timothée Chalamet is remarkable. And Monica Barbaro as Baez is fantastic. I love watching them sing together because they are so locked into each other. And Chalamet’s singing is damn good.

JC: He was amazing, right?

CE: They both were, I mean, stunning. And (the music) was all live.

JC: Yeah, no playback.

CE: I don’t know whether you ever caught grief for this, but in writing the screenplay, you obviously had to compress time for some scenes to work in the narrative.

JC: Here’s what I tell people: There are no inaccuracies in this movie. There are only choices.

CE: I think you can say that about every movie. Or at least maybe every good movie.

JC: Most of the time the research done for a movie is mind-bendingly thorough. You get volumes of information from researchers or associate producers — really heavyweight stuff. You take what you can use and put it where you want.

CE: I remember watching “The Age of Innocence” in the theater and thinking at the time that it’s a very interior movie. And then I went back and re-watched it, and it is not. It is absolutely exterior. It lays it all out for you. And it’s heartbreaking.

JC: The groundwork for that movie actually happened in college, when P.F. Kluge (’64 H’20) came up to me one day and he said, “You gotta read this book. It’s got the greatest last line of dialogue in American fiction.” He had me at that. And of course it was “The Age of Innocence.”

The great thing about Kenyon, at least at that time, was that it allowed you to identify yourself without struggling too much.

CE: I think you get to pick who you want to be, and Kenyon was very embracing.

JC: In a way, “A Complete Unknown” wouldn’t have happened without that sort of attitude at Kenyon. And it wouldn’t have happened without David Banks.

CE: That’s interesting. I think that movie, I’ve seen it now a couple of times, works on me like crazy. And my wife (Linda Djerejian Eigeman ’87) loved it, but it also worked on our kid. He was like, oh, this is what it is to be a creative person; this is how you live that way. Watching him watch this movie kind of broke my heart in the best way.

JC: Well, that’s one of the things that astonished all of us, was the emotional reaction that people have to this film. People singing along, people crying. There’s a lot of crying.

CE: There’s a lot of reasons to cry.

JC: I think that’s because this country is entering a long dark tunnel. To be able to look back and see there was light where you came from, when people weren’t sentimental and dismissive about hope — they weren’t cynical when they were truly idealistic. Bob could write and sing a song called “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ” and it was not about changes like this.

CE: Thank you very much for doing this. You know, I will hold onto “A Complete Unknown” and all of your other movies, but I will also hold onto the image of Bob Dylan scampering through the graveyard to Rosse Hall.

JC: And his Cuban-heel boots, as I recall.

CE: Yeah. Thank you again.

JC: My pleasure. Go Kenyon.

How the Philander Chase Conservancy is protecting Kenyon’s rural setting, one farm at a time.

Read The StoryDiscovering Kenyon’s Latin and Greek inscriptions, long hidden in plain sight.

Read The Story