A Lifetime with Bob Dylan

In a freewheelin’ conversation, Jay Cocks ’66 H’04 talks with Chris Eigeman ’87 about his Oscar-nominated…

Read The StoryHow the Philander Chase Conservancy is protecting Kenyon’s rural setting, one farm at a time.

Story by Adam Gilson

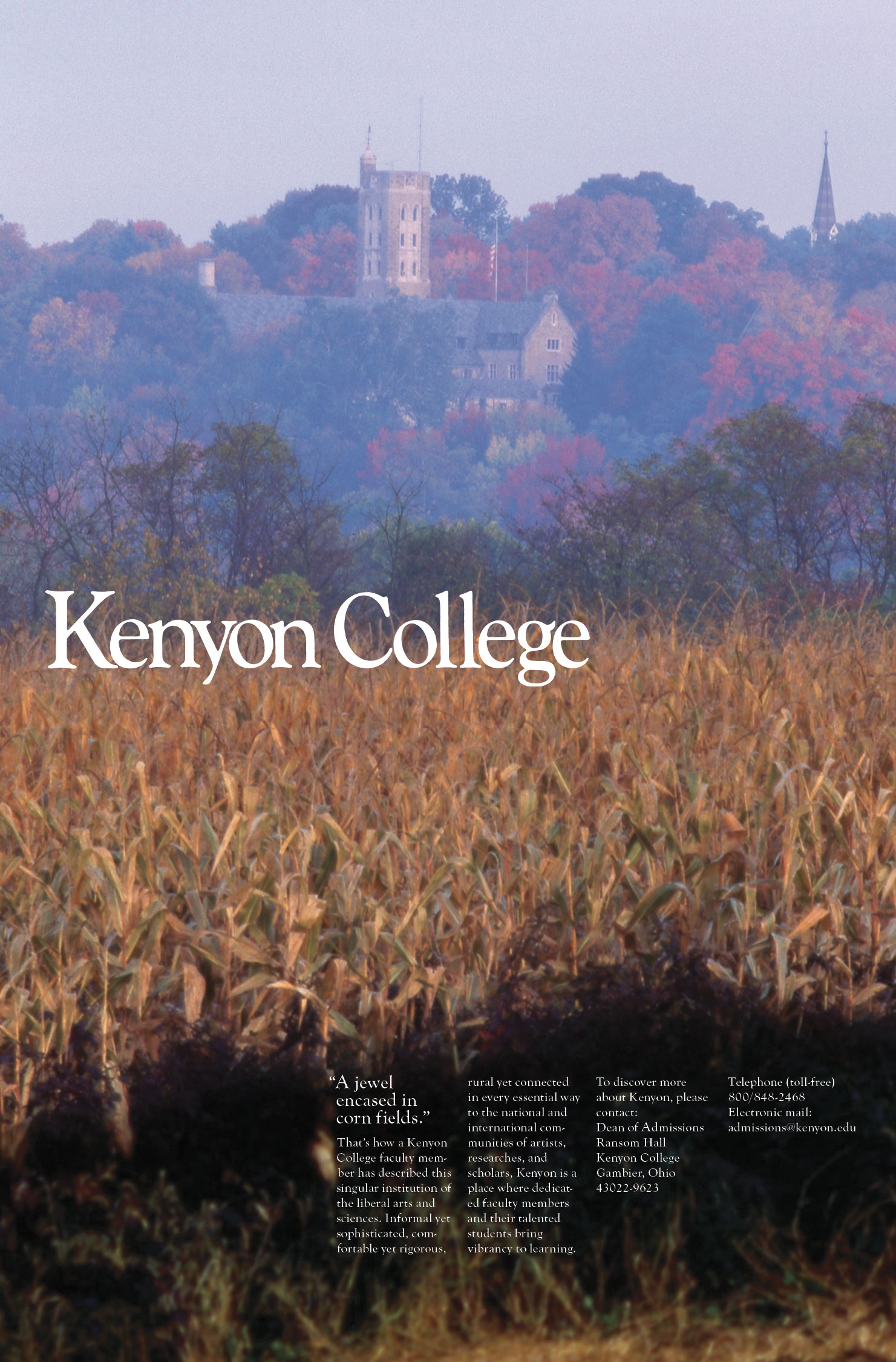

A 1990s recruitment poster shows a distant Peirce Hall, surrounded by a blaze of fall color, with cornstalks in the foreground ready for harvest. A caption calls Kenyon “A jewel encased in cornfields.”

This setting, deep in the Knox County countryside, feels eternal. But just a few decades ago, the community watched Columbus spread northeastward, turning thousands of acres of farmland into new suburbs. Soon, many feared, the farms and fields that had defined Kenyon since its founding might be lost forever.

But these fears never came to pass. Greater Gambier remains green today, thanks to the efforts of the Philander Chase Conservancy. In 2025, this Kenyon-affiliated land trust celebrates two milestones — 25 years of operation and 6,000 acres of preserved land.

Kenyon’s land preservation efforts began in 1987 as a response to two development proposals along Route 229 adjacent to the College’s main entrance — an RV park and a district zoned for business. By the end of the year, both proposals had been defeated, and Kenyon had acquired 267 acres of farmland as protection from development.

In 1995, the College purchased a farm across the Kokosing River to establish the Brown Family Environmental Center (BFEC). Kenyon raised $3 million from donors for land preservation efforts in the Claiming Our Place campaign (1998-2001) and ultimately established the conservancy, originally named the Philander Chase Corporation, in 2000.

Since then, with support from dedicated fundraising efforts and private donations, the conservancy has worked to preserve land in a five-mile radius around the College. The conservancy continues to purchase land outright, but the bulk of its efforts involve facilitating easements with landowners — both agricultural easements, which require land to be farmed in perpetuity, and conservation easements, which keep land open by restricting the types of development that can occur there.

The conservancy’s work does more than keep land free from development. Since its founding 25 years ago, the conservancy has made land available for recreation and research, and it’s helped preserve area farms at a time when agricultural economics have made farming increasingly challenging.

A field of sunflowers at Laneview Farm frames the long view to Gambier Hill.

Lee McPhail has lived most of his 85 years within view of Peirce Hall. He and his wife, Mary Ann, are the fifth-generation owners of Laneview Farm, which has overlooked the Kokosing River valley since 1827, the same year Philander Chase laid the cornerstone of Old Kenyon. Twenty years retired as head veterinarian for the Ohio Department of Agriculture, Lee lives at the end of a third-of-a-mile-long driveway that meets Route 229 east of Kenyon’s campus.

In one recent summer, the fields at Laneview Farm’s entrance were planted with five acres of sunflowers, with passers-by invited to cut some flowers for themselves and drop a few dollars into an honor-system cash box. The remaining tillable land of his 250-acre farm is planted in either corn or soybeans. Lee works in cooperation with Tim Norris, whose nearby farm is also protected by agricultural and conservation easements, to work the land. They split their proceeds during harvest season.

The land must be farmed, in accordance with the terms of an agricultural easement the McPhails sold in 2006, with partial funding from the conservancy and Knox County government. “The money’s very nice, a real good payday,” Lee said about the easement. The income helped buttress a farming operation that’s dependent on the ups and downs of the commodities market. But Lee was also motivated to work with the conservancy because of a shared desire to keep his land free from development, long after ownership passes to others.

Directly across 229 from his driveway is a row of houses on five-acre lots, built on land that was once part of an 80-acre farm. The subdivision was born of a similar desire for funds in a tough industry. “A lot of farms sell their frontage off,” Lee said. “That’s the way they make their retirement income.”

Thanks to the partnership between the McPhails and the conservancy, the rolling acres of Laneview Farm will remain in agriculture in perpetuity — and will never be broken into individual homesites.

The Hall Family Farm on New Gambier Road boasts an iconic red barn.

New Gambier Road, the back road from Mount Vernon to Kenyon, dips and wends through fields and forests on its journey to campus. Less than two miles from Bexley Hall, the road enters a wide-open bowl of land, with pastures on both sides. Two bright red barns and a red brick house are situated so close to the road that it feels like a private driveway.

This is the Hall Family Farm, and it’s been a gateway to Gambier for almost as long as Kenyon has existed.

“My great-grandfather and mother came from England (in 1850) and settled here,” said Alva Hall in a 1995 interview with Mara Bell Mancini ’95, as part of the Family Farm Project spearheaded by Professor Emeritus of Sociology Howard Sacks. “They made the bricks here on the farm … and built the house and raised their children.”

Six generations of Halls called the 150-acre farm home. And with Kenyon just down the road, the College was always part of their lives. “Kenyon’s always been pretty good to us,” said Hall. In the 1930s, he played with his Gambier High School basketball team at the former Rosse Hall gymnasium, the school and College teams alternating nights on the court. Later, Kenyon became a literal next-door neighbor; Brookdale Farm, part of the 267 acres the College purchased in 1987, bordered Hall’s acreage.

The Ohio Department of Agriculture’s Historic Family Farms Program named the property a Sesquicentennial Farm in 2016, in recognition of its 150 years in the Hall family. Mary Hall, Alva’s widow, continued to live in the farmhouse, renting her pastures to another farmer to raise cattle. By then, the rolling acreage was guaranteed to remain undeveloped in perpetuity. The conservancy had purchased a conservation easement from the family the year before.

Mary Hall died in 2020 at the age of 99. The following year, her son, Richard Hall, worked with the conservancy to sell the farm to Kenyon. Cattle still roam the hillsides under a lease agreement with an area farmer, who also leases the red-brick farmhouse.

Noelle Jordan, the director of the BFEC, has worked to build a network of hiking trails on the property, connected to the existing trail system on the center’s adjacent lands. Jordan is still formulating long-term plans for the property within the terms of the conservation easement originally negotiated by the Hall family. “It is highly restrictive,” she said. “The BFEC is working closely with the conservancy to ensure that future restoration efforts honor the spirit of the agreement.”

However the BFEC uses the property in the future, one thing is certain: the rolling lands framing New Gambier Road on this gateway to campus will forever resemble the landscape known to several generations of Halls and Kenyon alumni alike.

Completing a 1,100-acre ribbon: The conservancy’s purchase of 124 acres on Yauger Road (1), spearheaded and funded by longtime benefactor John Woollam ’62, connects Wolf Run Regional Park (2) with the Hall Farm (3), and Kenyon’s campus beyond (4). Mount Vernon (5) lies in the distance. View larger image.

Yauger Road begins at a Y-intersection with busy Coshocton Avenue, near Kroger, Chipotle and a combination laundry/tanning business. On the way to Gambier, it passes housing developments and the back sides of shopping centers. But at Upper Gilchrist Road, within view of two hotels, the landscape shifts back in time to acres of rolling hills covered with forests and restored prairie.

Mount Vernon’s eastward march stopped here as the 1990s ended, and there it will stay.

On the north side of Yauger Road is Wolf Run Regional Park, 260 acres with 10 miles of hiking trails. Known at one time as Prescott Farm, this tract once seemed destined to become more housing.

The preservation of this land was an early project for Douglas Givens H’10, the founding managing director of the conservancy who shepherded its work until his retirement in 2011. “A development company from Pennsylvania had already purchased land across the road from the Prescott Farm and planned to build 225 homes there,” wrote Givens in a 2013 Land Lines Magazine article. “Before the developer could purchase the farm as well, (the conservancy) bought it.”

The conservancy sold the land to the Knox County Park District the following year in order to establish Wolf Run Regional Park, but the developer continued with its plans to build on the south side of Yauger Road. It secured approval in 2005 to build houses on those 124 acres. Construction never began, although it remained a possibility. Instead, the land was leased to a large farming company that used it to grow corn and soybeans.

In 2023, the conservancy acquired the land in a deal spearheaded by John Woollam ’62 H’08, an educator, research physicist, electrical engineer and former Philander Chase Conservancy board member. Since the conservancy began, Woollam has directly funded half of its 6,000 preserved acres, including the land that is now Wolf Run Regional Park.

“That land has been farmed hard,” said Amy Henricksen, who began working with the conservancy in 2013 and now serves as its managing director. “There is significant erosion and loss of topsoil on the property, and the land needs time to recover.”

The first step in that recovery is a transition to natural prairie, work that Noelle Jordan and her BFEC team are leading. That work will rebuild the soil in preparation for the re-establishment of a forest of native tree species — including oaks, maples and hickories — on the entire tract. That work, which will help the College meet its own carbon-capture goals, will be multi-generational. “Centuries from now, the forest will look like it’s always been there,” said Jordan.

As the prairie and forest grow, the land will be available for research and recreation. During summer 2024, BFEC student researchers collected soil samples from the fields. Kenyon environmental studies faculty members Lauren Schmitt and Ruth Heindel will lead a long-term study, using future soil samples to track changes in soil composition as the prairie develops. And the BFEC staff is preparing a system of hiking trails that will be available to the public following a ribbon-cutting in June 2025.

Hikers will begin their journey on Schott Circle, a hiking trail named in honor of Lisa Schott ’80 H’22, who served as the conservancy’s second managing director until her retirement in 2022. They will continue on Woollam Way, into the Hall Farm property, through Givens’ Grove, and, eventually, into Kenyon’s campus. The Yauger Road property provides the final link in a continuous, 1,100-acre green ribbon running from Mount Vernon to Gambier.

For many years, Lisa Schott ’80 H’22 and Amy Henricksen have offered guided tours of the conservancy’s protected land during Reunion Weekend and other events. The current route is a 20-mile loop passing properties all around Kenyon. There’s Nancy and Spence Badet’s 50-acre woodlot on Canada Road north of campus. The Kokosing Nature Preserve on Quarry Chapel Road, a green burial cemetery founded by the conservancy in 2015, on land that was once known as the Tomahawk golf course. The Clutter Family Farm bordering the Kokosing River on Killduff Road, featuring an eagle’s nest and heron rookery. The 187-acre farm owned by Chrissie Laymon ’01 and her husband, Jay, at the intersection of Jacobs and Hopewell roads, with its red brick, Italianate farmhouse.

Distant view of Peirce Dining Hall.

As these 6,000 conserved acres pass outside the window, they show the struggle for local policymakers: how to accommodate the needs of a growing population while retaining the agricultural backbone of the community. Over the conservancy’s lifetime, Knox County’s population has increased by 19% to the current estimate of 63,320. And in that time, 25,000 acres of county farmland were converted to other uses, representing a 12% loss, according to an Ohio State University study.

The conservancy “has been one of the major players in farmland preservation in the county,” said Darrel Severns, the planning director for the Knox County Regional Planning Commission. “Anything that is kept in agriculture or conservation ground is a good thing. Of course, there are competing interests in the county of economic development and farmland preservation.”

Severns oversaw the writing of the Knox County Comprehensive Plan, released in January 2025. In its preamble, the plan describes these competing interests: “Knox County stands at a pivotal moment, facing significant decisions about growth and development. There has been and will continue to be pressure on the county and its jurisdictions for growth and development. At the same time, agriculture and rural landscape remain a cornerstone of Knox County, with a substantial portion of land dedicated to farming.”

This plan, a blueprint for government and civic leaders that will guide policymaking for the next decade, shows that concerns about the spread of suburban Columbus haven’t gone away. Stopping development is not the goal, but managing and directing that development is the challenge.

After 25 years and with 6,000 preserved acres, the conservancy has a seat at the table as these tough decisions are made. In the coming years, the conservancy will continue identifying new opportunities for purchases and easements, and raising the funds necessary to make them happen. And it will keep stewarding the landscape that it’s helped make eternal.

As the protected lands tour returns to Kenyon on 229, it passes Lee and Mary Ann McPhail’s Laneview Farm. It’s here, at the top of a long hill, that Kenyon is in full view, before the road descends into the Kokosing River valley. Rising above the valley, off in the distance, is Gambier Hill, with Peirce Hall’s iconic Philander Chase Memorial Tower overlooking it all.

In a freewheelin’ conversation, Jay Cocks ’66 H’04 talks with Chris Eigeman ’87 about his Oscar-nominated…

Read The StoryDiscovering Kenyon’s Latin and Greek inscriptions, long hidden in plain sight.

Read The Story