In Memoriam: The Latin and Greek Inscriptions of Kenyon College

Download the full catalog of inscriptions, compiled by Ellis Copley ’25, Chiara Nevard ’25 and Professor of Classics Adam Serfass.

Discovering Kenyon’s Latin and Greek inscriptions, long hidden in plain sight.

Story by Professor of Classics Adam Serfass

Once you start looking for Latin and Greek inscriptions at Kenyon, you notice them everywhere. Written on wood, stone and metal, these inscriptions aspire to permanency: they are texts from the past oriented toward us, in the future. Many are in public places, inviting us to read them. But Latin and Greek are no longer shared languages of the learned, as they once were, so these inscriptions are now silent.

To enable these inscriptions to speak again and to tell us what they have to say about the College’s 200-year history, two students — Chiara Nevard ’25 and Ellis Copley ’25, both classics majors — and I pursued a research project, funded by a grant from Kenyon’s bicentennial committee. We transcribed, photographed, researched and catalogued the inscriptions in a database, the Catalog of Latin Inscriptions of Kenyon College — in Latin, Corpus Latinarum Inscriptionum Collegii Kenyonensis, or CLICK, for short. (CLICK also includes one Greek inscription, but adding Graecarum would have ruined the acronym.) We published our findings in a 34-page illustrated booklet (PDF), which we distributed to those who joined us on one-hour walking tours of the texts last year on Homecoming, Family Weekend and Founders’ Day. The tours were well-attended — some 100 visitors joined us on Family Weekend alone — and what follows offers a taste of what we shared on our walks through the historical core of campus.

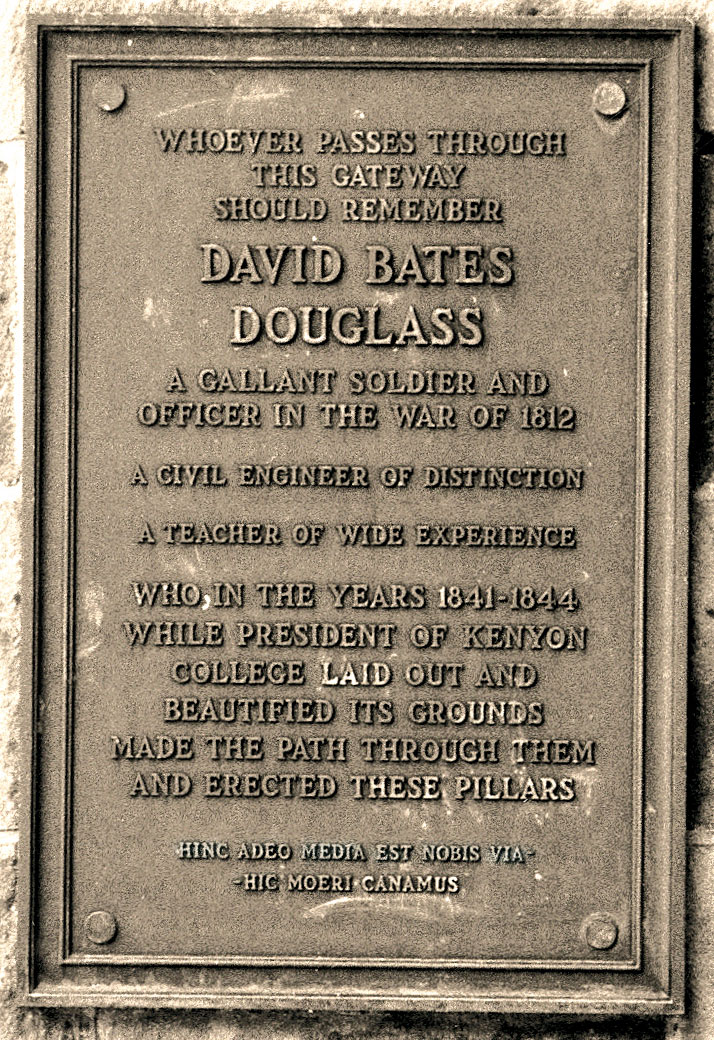

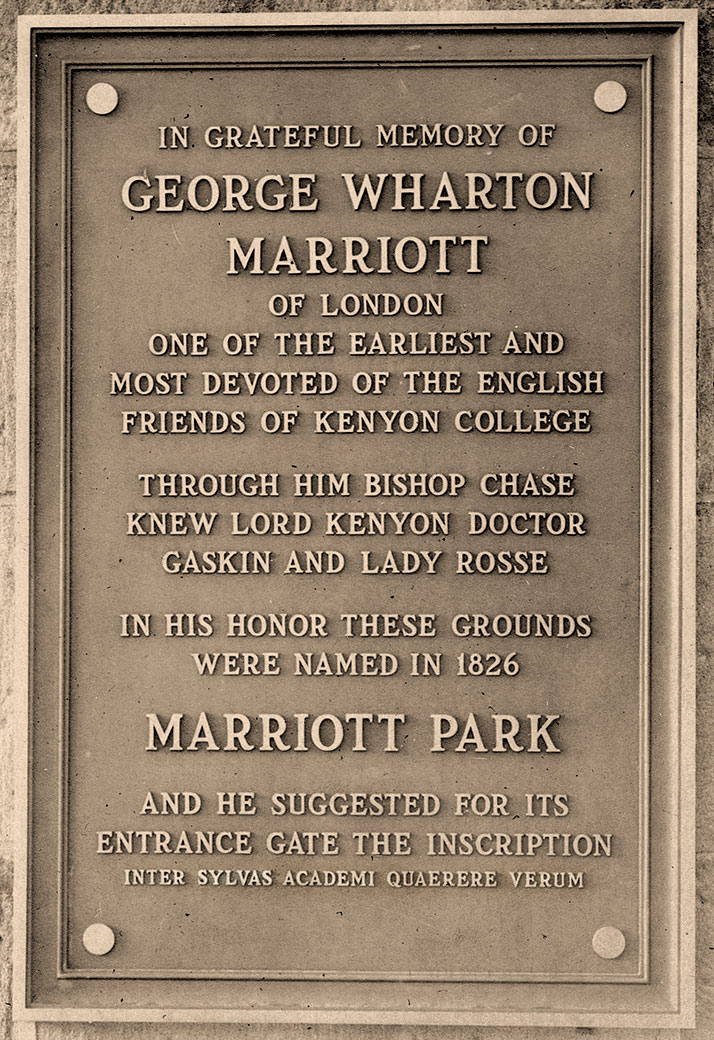

Our tours began at the College Gates, facing the two stone pillars that each bear a bronze tablet. You’ve likely passed through these gates many times, but how often did you pause to read what’s written on them?

The inscription on the east pillar reminds us that these gates and the path running through them — which appear timeless, as old as the College itself — were not, in fact, designed by Philander Chase, the College’s founder and first president, but by David Bates Douglass, Kenyon’s third president. Described as “a civil engineer of distinction,” Douglass helped survey the border between the United States and Canada, oversaw construction of the Morris Canal in New Jersey, and laid out the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. He also transformed Kenyon’s campus.

Upon arrival, he found Old Kenyon in a “dilapidated and filthy state” and the grounds in a “neglected condition.” Kenyon was a mess, for “everywhere there had accumulated through the years all that diversified litter which men living in College know so well how to disseminate about them.” These quotations are taken from the history of the College’s first century written by George Franklin Smythe, who also designed the tablets on the gates. The tablets were dedicated in 1924 during Kenyon’s centennial festivities, so it’s fitting to consider them now, soon after the College’s bicentennial.

As we know from a 1922 letter he wrote to William Foster Peirce, then Kenyon’s president, Smythe himself chose the Latin inscription at the bottom of the tablet on the east pillar: HINC ADEO MEDIA EST NOBIS VIA — / — HIC MOERI CANAMUS, “We have just half our way before us … here, Moeris, let us sing.” Smythe excerpted two partial lines of verse — the dashes in the inscription serve as ellipses — from the “Eclogues” of Vergil, the most celebrated poet of ancient Rome. In these lines, one shepherd-poet urges the other, named Moeris, to take a break, near the middle of their journey, in order to sing.

Out of the vast treasure-house of Latin verse, why did Smythe select these particular lines? To answer this question, it helps to know a bit more about the “Eclogues.” They are a collection of 10 pastoral poems set in an idyllic sylvan landscape populated by sophisticated rustics whose lives are spent not just in toil but in pursuit of wine, love and song. The world of Vergil’s “Eclogues,” then, is not entirely dissimilar to that of Kenyon undergraduates.

The verses allude to fundamental facets of the College’s identity. MEDIA NOBIS VIA, “half our way,” could also be rendered as “our Middle Path.” Smythe admits to this wordplay in an article he wrote about Douglass for the 1929 Yale Alumni Weekly. Note, too, that Vergil’s shepherds are toward the midpoint of their journey, just as this inscription stands near the midpoint of Middle Path. MEDIA VIA also evokes Anglicanism, the Christian tradition with which the College has been associated since its founding. Anglicans have often argued that they walk on a “media via,” a path midway between different theological traditions, such as those of Catholicism and Protestantism. Smythe himself was a clergyman in the Episcopal Church, a branch of the worldwide Anglican Communion.

No less suggestive is the phrase HIC CANAMUS, “here let us sing.” In ancient Rome, “here let us sing” means “here let us sing poetry.” Installed before Robert Lowell and John Crowe Ransom came to campus, the inscription exhorts those who read it to dedicate themselves to the literary arts. Kenyon has long been a singing college, where students mark milestones like Convocation and Commencement through communal singing. “Here let us sing” may even evoke a tradition that lasted till the mid-20th century: On Tuesday evenings, fraternity brothers strode down Middle Path from their lodges in the north to their dorms in the south, singing all the way. En route, each fraternity apparently sang a four-song set, a tradition so popular that it became a local tourist attraction. This tradition is not entirely moribund, for if you were standing before the gates on a given midnight, you might hear a similar sort of singing as students return home from their nocturnal adventures.

The inscription on the west pillar was also composed by Smythe. George Wharton Marriott was an English lawyer who corresponded with Philander Chase. As the text indicates, Marriott played a crucial role in Kenyon’s early history, for he introduced Chase to many of the notables who funded its foundation, among them Lord Kenyon, George Gaskin and Lady Rosse.

The tablet’s Latin inscription comes from the “Epistles” of the Roman poet Horace: INTER SYLVAS ACADEMI QUAERERE VERUM, “To seek truth among the groves of the Academy.”

The “groves of the Academy” refers to the school established by the philosopher Plato outside Athens’ walls, in a leafy locale not unlike Kenyon’s. Like the inscription on the east pillar, which recalls Middle Path, it ties Kenyon’s mission to its wooded, rural setting.

I recently served on the committee that revised Kenyon’s mission statement. Yet this quotation of Horace articulates the College’s mission far more succinctly and eloquently than we did: QUAERERE VERUM, “to seek truth.” The verb QUAERERE, to seek, is important, for it indicates that the College’s raison d’etre is the quest for truth, not necessarily its discovery. The word VERUM, “truth,” is ambiguous. Latin lacks articles, so QUAERERE VERUM could also be translated as “to seek a truth,” or “to seek the truth.” These small variations have big implications, and the Latin gives you room as a reader to decide for yourself which translation you prefer.

One final observation about the inscriptions found on the College Gates: the poets Horace and Vergil were near-contemporaries from the Golden Age of Latin literature. In this period, Rome was emerging from decades of near-constant war, political dysfunction and socio-economic devastation, into what many, including the poets on the pillars, celebrated as a new era of peace, prosperity and rebirth. Recall that these tablets were dedicated in 1924, just six years after the end of World War I, when the College was celebrating its centennial. Horace and Vergil may have seemed to Smythe the perfect poets to capture the hope and promise of postbellum Kenyon on the cusp of its second century.

The bronze tablets affixed to the College Gates are just over 100 years old. An invoice in the college archives indicates that the tablets cost $291 — the total includes bolts, screws and disks for mounting — and together weigh 207 pounds.

By Ellis Copley ’25 and Chiara Nevard ’25

After stepping inside the Church of the Holy Spirit to hear about the World War I and II memorials, and then visiting Ransom Hall to learn about the College seal and shield, the tours moved on to Ascension Hall and the tragic story of J.E. Campbell Meeker.

James Edwin Campbell Meeker came from a prominent Columbus family. Although he had long expected to attend Yale, upon meeting a couple of Kenyon students after graduating from high school and learning from them of Kenyon’s storied history and reputation, he changed his plans and matriculated at Kenyon in fall 1913.

When World War I broke out during his junior year, Meeker wanted to enlist right away but was persuaded to stay at Kenyon to finish his degree. He completed his course of study in 3 1/2 years, enlisting in the Army in the spring of his senior year. Given leave to return for Commencement, he received his B.Litt. with honors and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

After the war, he returned to Columbus and worked in his father’s company for a few years. He had just settled upon his dream of founding a newspaper when, at the end of May 1924, he died suddenly of a heart attack at age 29, a complication of influenza he had suffered during the war.

After their son’s death, Claude and Elizabeth Meeker donated $10,000 — equivalent to about $180,000 today — to fund the construction of a suite of rooms originally used as the College president’s office in his memory in Ascension Hall.

In memory of

J.E. Campbell Meeker

Bachelor of Letters 1917

A young man distinguished in beauty. How much majesty in him!

But now black night enshrouds his head in gloomy shadow.

O sweet devotion! Give lilies with a generous hand!

The inscription commemorating Campbell Meeker features a cento, a pastiche of phrases, from the sixth book of Vergil’s epic poem, the “Aeneid”; the cento incorporates phrases that memorialize a father’s grief for his young son.

The line O PIETAS DULCIS (“O sweet devotion”) does not appear in the “Aeneid.” However, it is necessary to complete the meter of the lines. It is likely that the whole cento was taken from an anthology of Latin verse, which would have been available to the Meekers as they were planning the memorial to their son.

In these lines, the hero Aeneas, a Trojan who travels to Italy and whose descendants eventually found the city of Rome, is in the underworld, speaking with his late father, Anchises. There, Anchises prophesies the future glory of Rome. He foresees the tragic demise, at the age of 19, of Marcellus, nephew, son-in-law and potential heir of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus. The parallel between Marcellus and Meeker is apparent: both are young men with promising futures whose lives are unexpectedly cut short.

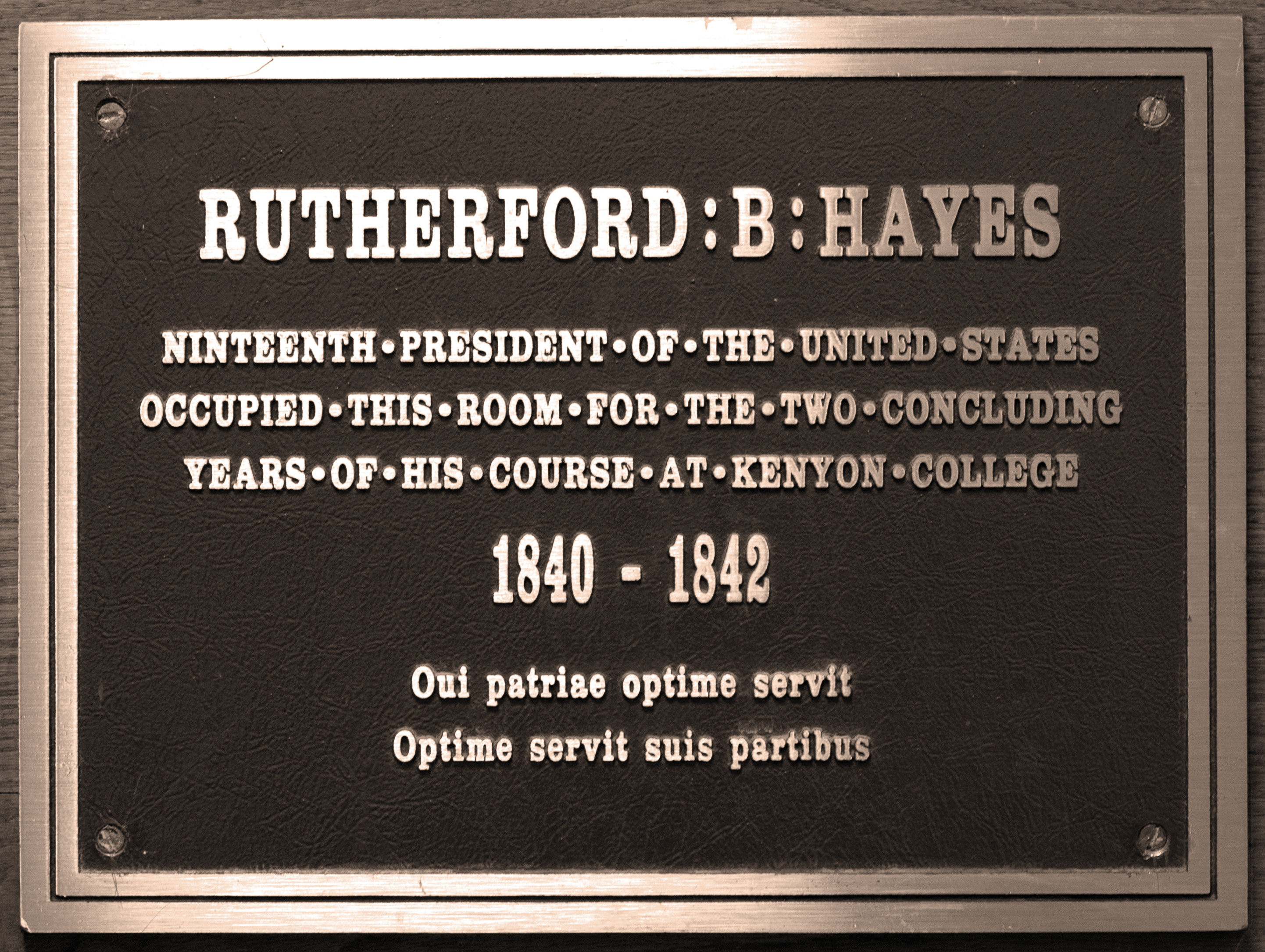

The final stop on the tours explored three lost, missing or now-inaccessible inscriptions. The most mysterious of these was a text from a bronze plaque mounted in Old Kenyon; we knew of its existence from a photo taken by a student in 2014.

Ten years later, Ellis searched the building for the inscription, but her hunt turned up nothing. So I tried — still nothing. But some of the custodians and campus safety officers I encountered while sleuthing recalled the inscription, so I decided to post the photo to social media, asking for leads. A graduate responded, saying he had seen the plaque being removed from the wall during the 2021-2022 academic year. Based on this tip, I had a hunch about where it might be. Last September, with the aid of a safety officer I’d met during my search of Old Kenyon, I was able, for the first time, to view the inscription. It was in good shape but now secreted in a remote and inaccessible corner of campus. Miraculously, in just a few weeks, the plaque was restored to its original location inside the east entrance of Old Kenyon.

This plaque is a reproduction of an earlier one that hung in the room once occupied by Rutherford B. Hayes, Class of 1842, whence, it is said, he frequently regaled passers-by with impromptu recitals on the ukulele. Its Latin inscription bears a welcome message: Qui patriae optime servit / Optime servit suis partibus, “He who serves his country best / best serves his party.”

But in reproducing the Latin text of the original plaque, this new one makes an unfortunate error. Look closely at the image of the Latin inscription, at its first word. For the inscription to make sense, that word should be Q-U-I, “he who,” but is in fact O-U-I, “yes!” A French exclamation intrudes on the Latin couplet. This is an unfortunate typo, one immortalized in bronze. (The plaque also misspells the word “nineteenth.”) When I mentioned these errors to a member of the bicentennial committee that funded our project, she suggested that perhaps we should have the errors fixed. But I said no, on pedagogical grounds, because the inscription offers an object lesson in the importance of proofreading.

Professor of Classics Adam Serfass, who joined the Kenyon faculty in 2002, teaches a wide range of courses in Greek, Latin, ancient history and rhetoric. For his work in the classroom, Serfass has received a teaching fellowship from the Whiting Foundation and Kenyon’s Trustee Teaching Excellence Award.

Download the full catalog of inscriptions, compiled by Ellis Copley ’25, Chiara Nevard ’25 and Professor of Classics Adam Serfass.

As a senior at Kenyon, I find myself often reminiscing about my time here. The memories come sporadically. I’ll be walking along Middle Path, on a particularly crisp morning, and suddenly I’ll remember how it felt to first watch the leaves change, to have my first class in Ascension, to avoid the College’s seal in Peirce for the first time.

I then think about all the other students who have come before me, who have experienced the same or similar moments. Most colleges boast a rich and deep history. However, maybe it’s Kenyon’s historic buildings, or the matriculation book, or the community built on this isolated hill, but I feel that Kenyon’s history is less that of an institution and more that of a familial line. At Kenyon, you walk the same path that many have walked before you. You create your own path in this world, while following the example and tradition of those who walked before you. Through this project, I hoped to learn more about the history of Kenyon, to shed light on the forgotten inscriptions, and, maybe a little selfishly, to leave a legacy of my own at the institution that truly shaped me into the person I am.

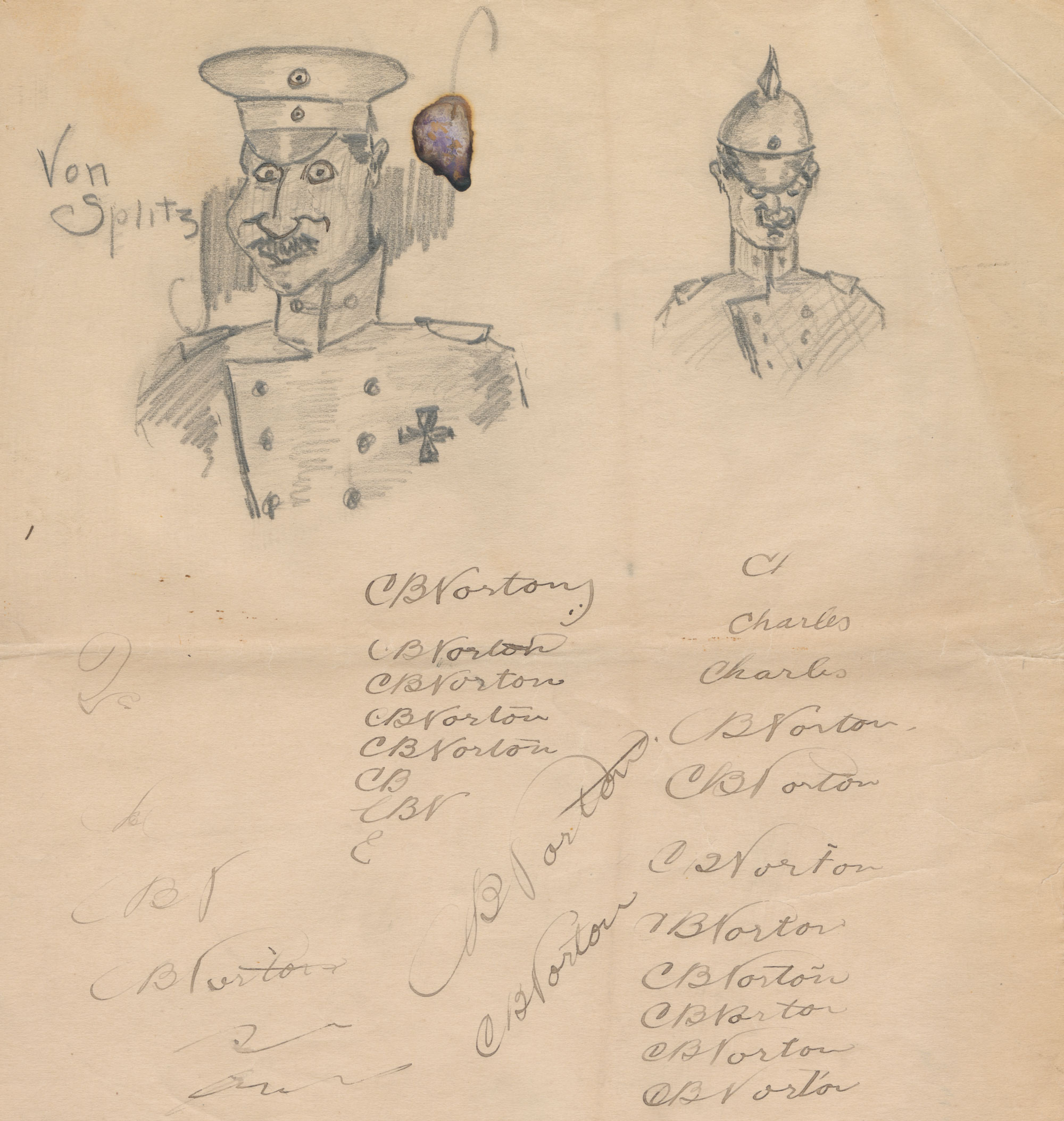

One day, I was digging through the archives to find more information about Kenyon’s involvement in World War I. I was on my third or fourth manila envelope of files, and feeling a little exasperated, when I came across a sketch drawn by a soldier. It was a rough little drawing, of no strategic significance, with no information about the facts of the war, more humorous than anything else, but it gave me pause. I took a picture of it and sent it to my brother. He is a pilot in the Air Force, and that sketch reminded me of him because, well, it was exactly something he would draw. I was first interested in this project because I love the human side of history. The preserved details of lives that demonstrate the continuity of human nature. And this sketch, drawn by a young man over 100 years ago, reminded me of my brother. I wish I could properly convey that feeling in words, but maybe we aren’t supposed to be able to write about everything. There are some sensations that can only be felt.

A personal connection

A soldier’s sketch caught Copley’s attention during a research trip to the College’s Special Collections and Archives.

During my time on the Hill, I have seen Latin inscriptions like those on the Gates of Hell and in the Campbell-Meeker Room and have always wondered about their origins and significance.

We were surprised at how many Latin and Greek inscriptions we found around campus. For example, in the archives I found a letter dating to 1983 from Lord Kenyon, the 5th Baron of Gredington, to a student writing an article in the Collegian. Lord Kenyon discussed the history of the Kenyon seal, which was adapted from his family’s coat of arms, in use since the 16th century.

As a classics major and Latinist, I appreciated learning more about the College’s history. I am grateful that we were able to rediscover these neglected inscriptions, and, through this project, I hope the broader community has a better understanding of the College’s history as well as a greater appreciation for classics.

In a freewheelin’ conversation, Jay Cocks ’66 H’04 talks with Chris Eigeman ’87 about his Oscar-nominated…

Read The StoryHow the Philander Chase Conservancy is protecting Kenyon’s rural setting, one farm at a time.

Read The Story