See Inciardi's Mini Print Vending Machines in action through her TikTok account.

Art In Season

Craftsmanship and entrepreneurial acumen collide in the buzzworthy food prints of Anastasia Inciardi ’19.

Story by Carolyn Ten Eyck ‘18

Put four quarters into the machine, and a surprise 2.5 x 3.5” linocut print comes out. Whether you’ll get a print of a single olive, a Cheez-It or a piece of farfalle, it’s luck of the draw — and part of the fun. The Mini Print Vending Machines constructed by artist Anastasia Inciardi ’19 have become something of a sensation. Take it from the New York Times Magazine, where the machines were featured: “Anastasia Inciardi has found a new way to connect with collectors.”

The idea was born in the summer of 2020, when the U.S. Mint shutdown and mandates on businesses led to a nationwide coin shortage. Quarters were temporarily hard to come by, so Inciardi found an innovative way to acquire some by selling prints for quarters in a mechanized fashion. (“I needed quarters to do my laundry,” Inciardi said. “So I got a machine made.”)

Inspired by Art-o-mats — repurposed cigarette vending machines that dispense cigarette- pack- sized art — and the temporary tattoo and sticker machines often found at supermarkets, Inciardi’s vision became a reality last year, when the first Mini Print Vending Machine was temporarily installed at Soleil, a shop down the street from her studio in Portland, Maine, where Inciardi lives with her fiancée, Addison Wagner ’18, a farmer and artist.

An Instagram reel showcasing the machine went mega-viral in June, gaining over 18 million views and nearing a million likes. Inciardi won’t reveal how she sources the vending machines — there already have been some copycats — but she sees the project expanding in the future. The vending machines have a waiting list of hundreds (including a Kenyon art professor who submitted a request for one on campus). “I’m putting a few in New York and London, and hopefully some in Edinburgh and Amsterdam,” said Inciardi. Most recently, one was installed in the Whitney Museum of American Art. The whimsy and public-facing nature of the project garnered a huge positive response, a big leap for someone whose entrepreneurial acumen and eye for audience engagement have brought her business steadily increasing returns for years. Her growing number of followers even offer print ideas (she keeps a running list of audience-generated suggestions).

For Inciardi, art has always been a central force.

She began interning and working in museums in her hometown of New York City at the age of 14, and came to Kenyon wanting to study and create art. But, as a studio art major, finding the right channel for her creative aspirations proved to be tricky. Then, in a “History of Printmaking” class sophomore year, Visiting Assistant Professor of Art History Jill Greenwood handed out pieces of linoleum and carving tools with simple instructions: carve a print.

“From then on, I was obsessed with print-making,” said Inciardi. She began carving out of rubber in her Mather dorm room, making new prints every day. That semester, she started selling her works for the first time, printing and advertising T-shirts on Instagram and donating the proceeds to Planned Parenthood in the wake of the 2016 presidential election, when reproductive rights were front-of-mind for many.

In her senior year, she took the studio art printmaking course with Associate Professor of Art Craig Hill, along with her sister, Alex Inciardi ’21. Though she’d been making prints out of her residence halls the past few years, this was the first official training she’d had in the art form.

Over the course of the semester, she experimented with multi-color prints and different techniques. “In the beginning, her prints were really quite simple,” remembered Hill. “Every-thing was blue, and she would have string or stencils to block out designs. And she would make a hundred of them a week, you know, and they’re all slightly different.”

She and Hill bonded over their shared passion for collecting small toys and objects. “She started doing these gorgeous linoleum cuts of these objects, like a can of sardines,” said Hill. “That’s when her work became really personal, because it was about the things that she collected and found interesting.” For her senior exhibition, Inciardi asked people to send in photos of their own objects and used those images as the basis for a series of prints — an object portrait project, of a kind — from the hundred or so pictures she’d received.”

Hill remembers an open studio night during Inciardi’s senior year as a turning point for her burgeoning print business. “She put out her prints and sold them for around $5 apiece, and she made like $500 in a night.” From there, she knew she had something.

The ability to produce a lot of prints at once appealed to Inciardi’s artistic sensibilities.

Creating multiples for each print helps keep her prices low and her art accessible to a broad audience. “I’m using my hands and a machine to make multiples of a certain work of art, and it’s still unique,” she said.

There’s a business savvy to this practice, too. The quantity of prints she’s able to generate and sell in a short time is large in comparison to the output of artists in different fields. Hundreds of people can purchase an iteration of one print and receive a handcrafted product. “Ana’s getting a good return on the amount of time that she spends on it, which is tricky for artists,” said Wagner.

After Kenyon, Inciardi anticipated a career in the museum world and interned at the Metropolitan Museum of Art following her graduation, focusing on exhibit design. But the COVID pandemic brought about a moment of reckoning. “I had to make a decision about what I wanted to do with my life, and that was this,” she said. Moving with Wagner to Portland, Maine, in June 2020 was a big leap. Both had been planning on finding food service jobs, which were hard to come by in a city dependent on tourism revenue during a pandemic. Instead, Wagner found farm work, and Inciardi went all-in on her print business.

With no shortage of gifted artists showcasing their work on social media, it can take more than craftsmanship and talent to stand out.

For Inciardi, who’s been sharing and selling her art for nearly as long as she’s been making it, finding her creative niche was the best entrepreneurial decision she made.

“I looked at my work and I thought about what brings me the most joy,” said Inciardi. “My family is in love with food — we’re Italian Americans. What we’re eating and what we’re making and cooking are the things that connect me the most to my family. My grandmother calls me all the time and asks, ‘What are you cooking right now?’ And Addy’s a farmer. So it couldn’t have made more sense.”

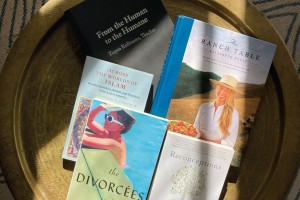

The produce Wagner brought home from her work proved to be great inspiration. Garlic scapes, red cabbage and rainbow chard all have a place on Inciardi’s online storefront. Her art celebrates, too, the processed joys of the culinary world. Jars of Maraschino cherries and jams, boxes of Annie’s mac and cheese and cones of sprinkle-encrusted soft-serve ice cream are well-represented. “Food is nostalgic and brings people joy,” said Inciardi. “I got into this niche that just opened up the whole world for me.”

Now, Inciardi is collaborating with the likes of tinned seafood company Fishwife and fashion designer Rachel Antonoff.

Fishwife was named one of Ad Age’s Hottest Brands in 2023, and Antonoff is known for her social-media-friendly statement pieces.

Working with brands and food companies generally involves sending scans of prints, but occasionally the collaborations get hands-on. “There’s a restaurant in Copenhagen called Noma, and their co-founder is opening a restaurant in Brooklyn, named Ilis, and I’m doing their menu for them. I’ve made like 60 prints. It’s not like a traditional menu — every single ingredient has its own card, in the shape of a tarot card. So when the diner sits down, the ingredients are put in front of them (in print form). I’ve been working on this project for months.”

Inciardi has a knack for hopping on pop culture trends early — last summer, she made a negroni sbagliato print (for the chronically online: if you know, you know) — and often returns to familiar pantry staples for inspiration. After making a print of a carton of Miller High-life Pony, she worried she’d get a cease-and-desist letter in the mail from the company. Instead, they sent her a box of merch. For Inciardi, the beauty of focusing on food is the breadth of specific references to pull from. “I’ve probably carved 500 foods already, but there are so many more to do,” she said.

Recently, Inciardi’s work led to a surprising family discovery. One of her first popular prints was of a tomato, carved at the request of classmate Eve Bromberg ’19. While checking out her website’s visibility by entering various word combinations into Google’s search bar, “Inciardi tomato” brought her some unexpected results.

The Inciardi tomato was more than one of her prints — it was also a variety of paste tomato named for her family. In 1898, her great-great-uncle Enrico Inciardi emigrated to the United States from Sicily, arriving at Ellis Island with heirloom seeds stitched into his clothing. Enrico eventually settled in Chicago. Anastasia’s side of the family, based in Brooklyn, had no idea about the tomato variety, which was lapsing into obscurity at the time she found out about its existence online.

One of the last farmers growing the Inciardi tomato is based in Ravenna, Ohio — around a two-hour drive from Kenyon. Inciardi got in touch, and the farmer sent over some seeds, which Wagner propagated at the organic farm. After successfully soliciting grant funding, the pair are working together on a zine-type art book about the tomato and other seed stories. A bonus? “The tomatoes are delicious.”

This book marks the couple’s first artistic collaboration. “She’s meticulous and likes to work on something for a very long time, and I like to work at the very last second, and I’m really fast,” said Inciardi of Wagner. “It’s been fun to work on something that involves both of our interests,” said Wagner. “It’s very meaningful because the (Inciardi) tomatoes were about to enter oblivion, and now a lot of people are interested in growing them in their home gardens.”

They’re also wearing them. On Rachel Antonoff’s website, a trapeze-style dress is patterned with Inciardi’s tomatoes on the vine, and her green tomatoes bedeck a cotton- and-cashmere cardigan.

“I love working with Ana so much,” said Antonoff. “She is such a gifted artist, and her process is endlessly fascinating and cool to me.” Becca Millstein, the co-founder and CEO of Fishwife, echoed the sentiment: “She’s an absolutely brilliant artist and businesswoman, and that is a rare breed in this world.”

In a way, Inciardi’s tomato prints are a micro-cosm of the formula that makes her work so suc-cessful: vibrant visuals that evoke strong sensory reactions. You want to eat her work, or inhale it. Steeped in cultural history and personal taste, the details that inspire Inciardi also resonate widely across audiences.

Also In This Edition

Making Waves

Kenyon’s swimming and diving program is having a ripple effect far beyond Gambier through the swimmers who have…

Read The StoryThe Ins and Outs of Getting In

As college admissions adapts to an ever-shifting and increasingly competitive landscape, we break down what has…

Read The Story