Making Waves

Kenyon’s swimming and diving program is having a ripple effect far beyond Gambier through the swimmers who have…

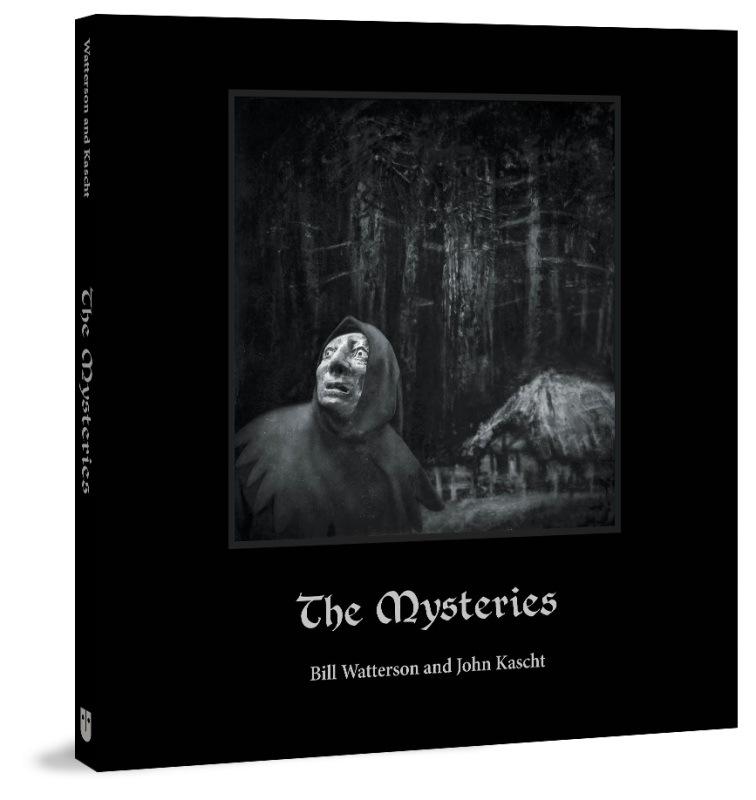

Read The StoryExploring “The Mysteries,” a new, and surprising, book by Bill Watterson ’80.

In 2011, The Onion poked fun at Bill Watterson ’80 in a satiric post that imagined Watterson having drawn a new installment of his wildly popular comic strip, “Calvin and Hobbes,” every day since it ended in December 1995 and subsequently feeding it daily into a paper shredder. “Wow, this might be one of the best yet,” Watterson quips in the piece as he destroys an imagined 5,689th strip.

While amusing, the item was a bittersweet reminder of how beloved “Calvin and Hobbes” remained years after Watterson ended it. It also highlighted Watterson’s disappearance from the public eye afterward as he gave virtually no interviews and didn’t pursue a second professional chapter as an illustrator or painter. (He didn’t respond to this magazine’s requests for comment.)

As a result, news that Watterson was publishing his first non-“Calvin and Hobbes” book immediately ignited interest in and nostalgia for Watterson and his iconic strip. “The Mysteries,” a short fable co-created with illustrator and caricaturist John Kascht, appeared in October 2023 and quickly topped bestseller lists. While its folklorish aura and dark themes may puzzle diehard “Calvin and Hobbes” fans, “The Mysteries” and its unique illustrations reflect an observation that Watterson made in a 2014 interview with Jenny Robb, curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at The Ohio State University, which holds a collection of more than 3,000 original “Calvin and Hobbes” strips and related materials. The interview was conducted for the museum’s catalog of a comprehensive exhibit of “Calvin and Hobbes.”

“Art has to keep moving and discovering to stay alive, and increasingly I felt that the new territory was elsewhere,” Watterson told Robb.

Post-“Calvin and Hobbes,” Watterson delved more deeply into painting, an artistic evolution evident in the moody and layered illustrations in “The Mysteries.” But by his own account, Watterson — a political science major — didn’t take a single painting class at Kenyon. He did enroll in several art classes, however, including drawing, life drawing and printmaking. “I knew they’d be teaching us about color, and the idea of sitting there mixing colors seemed soooo tedious,” he told Robb. “So I skipped that, and had to figure it all out the hard way twenty years later.”

In Watterson’s era, Kenyon’s art department took a traditional, almost classical approach in its instruction that he was able to combine with his background in cartooning, said one of his instructors, Professor Emeritus of Art Martin Garhart, who painted with Watterson in New Mexico.

“You look at the way he develops the landscape, he had a really good sense of how you develop an image traditionally,” said Garhart, who now works out of a studio in Powell, Wyoming.

Over the years, Watterson pursued fine arts painting on his own, including en plein air or outdoor painting during the time he lived in New Mexico before returning to Ohio. He continued to paint after ending the strip, exploring the medium but with no plans to exhibit. “Well, never say never, but I don’t currently paint with that kind of ambition,” he told Robb in 2014.

It was around the same time that Watterson decided to give himself a painting subject by writing a story. The result, “The Mysteries,” wasn’t what he expected, nor did he have any idea what the illustrations should be.

“So the story sat in my desk drawer for years,” Watterson said in an official Andrews McMeel video interview released in conjunction with the publication of “The Mysteries.” “I made periodic attempts at it, but I could not figure out what this thing wanted to be.” (Andrews McMeel also published a second and more familiar Watterson title this year, “The Calvin and Hobbes Portable Compendium Set 1,” featuring strips from 1985 to 1987, the first in a planned seven-volume series.)

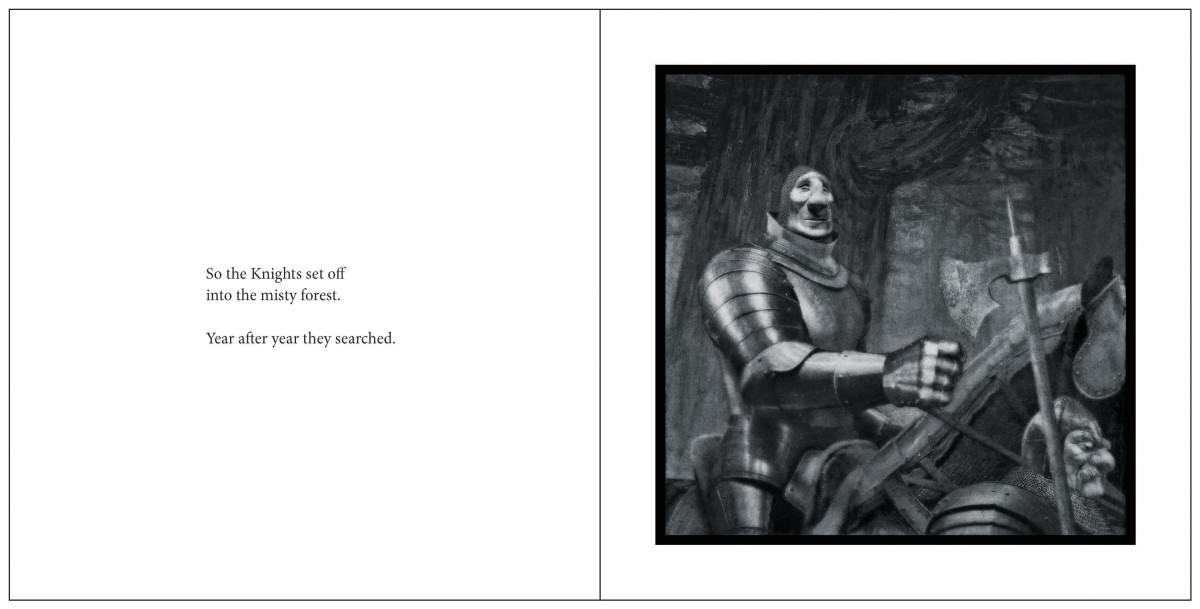

Eventually, Watterson and Kascht talked about collaborating on something related to Watterson’s story. One of their hard and fast rules would come back to haunt them, but ultimately in a positive way: neither had final say and either could veto anything or simply pull the plug on the project. Soon they were exchanging ideas and trying different approaches, but neither man was satisfied. So back to the drawing board they would go.

“Our process was appallingly inefficient and wasteful,” Watterson said in his Andrews McMeel interview. “We were basically drawing the map as we wandered around lost. But when you’re lost, pretty much everything is surprising.”

For example, Watterson was more interested in capturing the nuances of a subject, whereas Kascht wanted something more realistic. As Kascht told Andrews McMeel, “It would be hard to overstate the incompatibility of our creative approach.”

Watterson’s description of their process struck a familiar chord, said Professor Emeritus of Art Gregory Spaid, a painter in Gambier who also taught Watterson at Kenyon. Wandering around lost “is kind of a description of making art, especially at the beginning stages of working your way into a project or a series,” Spaid said.

Watterson and Kascht broke their amicable deadlock when Watterson suggested that Kascht sculpt a series of heads that could audition as characters. In due time, a box of clay heads arrived at Watterson’s studio and he began seeing possibilities. “Choosing a head almost randomly would bring new interpretations to the figures,” Watterson said. “They were constantly surprising. They started shaping the pictures by themselves.”

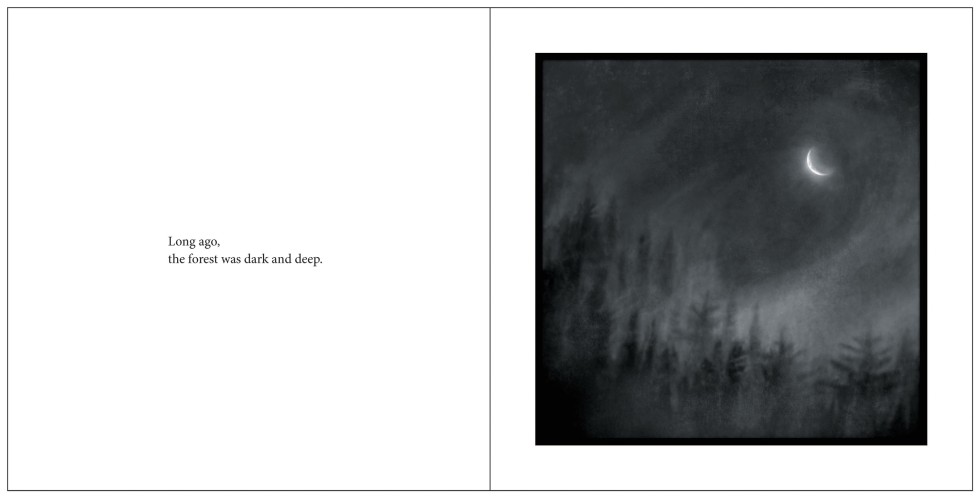

So what is “The Mysteries” about? Well, it’s a little hard to say. At first blush, it recalls journalist and author G.K. Chesterton and one of his most frequently quoted lines, about the precautions people should take when removing fences whose purpose they no longer understand. In that vein, it’s easy to interpret “The Mysteries” as a climate change parable: as people in a medieval-like kingdom overcome their fear of unknown entities called the Mysteries with their “bizarre and terrifying powers.”

Eventually, when a Mystery is captured (it’s never described or portrayed), people lose their fear of them, chop down the forest where the Mysteries dwell, and tear down “enormous walls” erected to protect the kingdom.

But as modern life intrudes in the form of mass media, highway congestion and urban overdevelopment, the sky turns “a slightly weird color,” acrid smells drift in from across the sea, animals migrate to far corners of the earth and things begin to disappear.

Although not the last line in the book, the most telling might be this sentence, appearing opposite what appears to be a thick mist or smog partly obscuring the moon: “Rather late, the people grew alarmed.”

Among those not surprised by the book’s dramatic departure from Watterson’s comic strip days was his biographer, Nevin Martell.

“He was never going to be the guy that came back with ‘Calvin and Hobbes 2.0,’ or even another comic strip,” said Martell, author of “Looking for Calvin and Hobbes: The Unconventional Story of Bill Watterson and His Revolutionary Comic Strip.” “He clearly felt like he did all he could have done with that medium and he wanted to move on.”

In Watterson’s 2014 interview with Jenny Robb, he cited painters he admires including late Titian, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Vermeer and, in particular, Lucian Freud. He described Freud as having “a cold eye, but great sense of physicality and weight,” a description that could also be true of some of the illustrations in “The Mysteries.”

“Collaboration generates friction, but also energy,” Watterson said in the Andrews McMeel video. “And sometimes the combination of talents is greater than the sum of the parts. We set off looking for surprises, and we got them every day. So be careful what you ask for.”

Collaborating on The Mysteries - Bill Watterson and John Kascht

(2023 video interview with Andrews McMeel Publishing)

The Kenyon Cartoon Connection

(1988 issue of the Kenyon Alumni Magazine)

Kenyon’s swimming and diving program is having a ripple effect far beyond Gambier through the swimmers who have…

Read The StoryAs college admissions adapts to an ever-shifting and increasingly competitive landscape, we break down what has…

Read The StoryCraftsmanship and entrepreneurial acumen collide in the buzzworthy food prints of Anastasia Inciardi ’19.

Read The Story