Linking Arms

An immensely complex transplant operation gives a soldier two new limbs. On the team that made it happen: a husband…

Read The StoryKenyon's first females graduated forty years ago. To mark the occasion, the Bulletin recalls how coeducation came about — from the fiscal crisis, to the clamor, to the uneven welcome on the Hill.

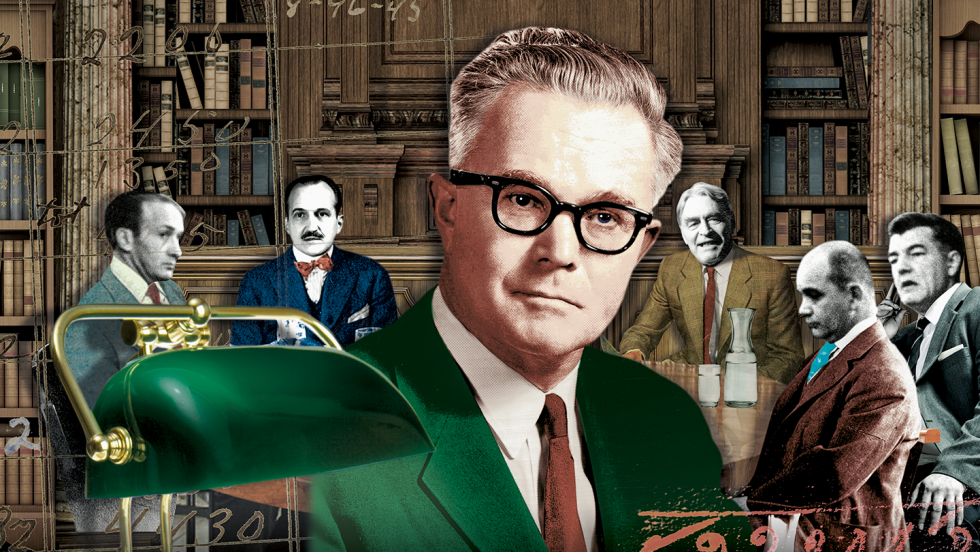

Story by Joel Hoekstra | Illustrations by Matt Herring

Kenyon’s first class of women celebrated their fortieth reunion this year—an anniversary that passed without much notice, because today coeducation feels normal, logical, inevitable. The view in the mid-1960s was very different. The proposal to admit women enraged alumni and upset some students. And when the women finally arrived, the College was not exactly ready for them. Here’s an account of the historical moment that would transform Kenyon—and save it from financial ruin.

That was the question facing the all-male board of the all-male college as President F. Edward Lund convened the trustees’ annual meeting in Gambier on a Saturday morning in early June 1964. Bishop Roger Blanchard opened the proceedings with a prayer, perhaps hoping that God Almighty would spare them the terrible choices before them.

Kenyon was nearing financial ruin. For more than a decade, the College had been operating at a deficit. The revenue generated by an enrollment of roughly 600 students no longer kept up with expenses. Financial support among alumni was tepid, and the school’s endowment was tiny. The College had more than $1 million in unpaid bills.

The future looked bleak indeed. Yet Kenyon’s predicament was hardly unique among small American liberal-arts institutions. In 1963, a report issued by the Ford Foundation warned that no school with fewer than 1,500 students could remain solvent past 1975.

President Lund had read the report and dismissed its conclusions, saying an enrollment of about half that figure—or 750 students—was “really ideal” for Kenyon. He had turned down a grant from the foundation to fund enrollment-expansion plans. Quality schools—no matter the size—would always attract students, he assured the board. Private education had always sold itself.

But Lund’s lieutenants remained alarmed. Treasurer Samuel Lord took one look at the balance sheet and informed the senior staff that “Kenyon cannot survive financially” without a significant increase in revenue. Bruce Haywood, who had recently become provost, pressed for a special committee to study the matter. In March 1964, a group of alumni, administrators, and consultants met to consider the only viable fix: boosting enrollment. Like a covert operation, the deliberations were endowed with a secret-sounding name, “Quo Vadimus” (Latin for “Where Are We Going?”).

The conclusions, Haywood told the trustees assembled that June morning, basically boiled down to two options: adding more men (difficult, according to the Admissions Office), or bringing women to Gambier.

The addition of female students wouldn’t necessarily mean going coed, Haywood quickly added. Rather, a separate institution of sorts would be built: a “coordinate college” that housed hundreds of women. Females would attend classes with males, but live apart. They would generate revenue. They would save Kenyon without diluting what Haywood called Kenyon’s “essential character.”

“I see a great many advantages, and, frankly, very few disadvantages,” the provost told the board. Among Kenyon’s faculty, he claimed, there was “very real enthusiasm for such a college.”

No sooner had Haywood finished speaking, however, than a wealthy trustee leaped to his feet and declared, “Women ruined Harvard! They will never ruin Kenyon!”

Cooler heads prevailed. In February 1965, after eight months of further study, the board approved a proposal to build a Coordinate College for Women, which would admit roughly 175 female students in the fall of 1969. As news of the plan leaked out, alumni and students reacted, often vehemently. Opponents of the idea were in the minority, Dean of Students Thomas Edwards later recalled in an interview: “But like any minority, they could be very vocal.” Breaking the news to a roomful of alumni in Cleveland was like “setting off a bomb,” Haywood recollected. Many alumni saw the move as a ruse to somehow transform Kenyon—the only college in Ohio that allowed alcohol—into a dry campus.

“I for one have vowed not to contribute one cent toward what I feel is the destruction of the Kenyon I knew,” Robin F. Goldsmith ’65 wrote in a letter to the Collegian. “Dean Haywood seems convinced that there are lots of girls on the farms of Ohio who are the intellectual equals of Kenyon men but who have no Kenyon of their own . . . Kenyon stands to lose from the full-time presence of girls.”

Students also balked at the plan. A campus poll indicated that more than half of the 644 students opposed entry of women. Steven Silber, chair of the Students’ Committee Against the War in Vietnam, told a journalist: “Women would be in the way. You can get hung up on women.”

“They’ll ruin the school,” David Thomas ’69 told the Mansfield News-Journal, while Walter Butler III ’68 P’01 explained to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “We like women—when we want them. But not cluttering up the Hill all the time!”

Steve Cashell ’71 , however, disagreed. “Having girls on campus will relieve a lot of pressure,” he told a journalist, with a wink.

Meanwhile, Kenyon’s administrators, having committed themselves in theory to welcoming women, focused their attention on the accommodations such a change would require. Plans were drawn up for four new residence halls—today known as McBride, Mather and Caples (the fourth dormitory was never built). The new dorms would cluster women in sixteen-person “social units” (or “nests,” one administrator later recalled) and would feature a curved “feminine” design, according to the architect’s notes. Course offerings in the arts and humanities were beefed up, recalls art professor and former provost Gregory Spaid ’68, based on the assumption that women would prefer those subjects to, say, mathematics or the hard sciences. And the trustees, to their credit, acknowledged that maybe a goose or two would be good for the ganders in their own ranks as well: September 1968, two women were added to Kenyon’s board.

The new Coordinate College would be overseen by a female dean. In December 1968, Kenyon officials selected Doris Crozier, a professor of anthropology and former assistant to the president of Chatham College, to fill the role, extolling her “excellent background in both administration and academics.” An international traveler who had lived and taught in Germany and Cambodia, Crozier knew something about foreign cultures—an understanding that, as the sole female member of an all-male administration, would serve her well.

In hindsight, Kenyon’s preparations were insufficient. No one seemed to have given any thought to women’s athletics. “There was not preparation for women in physical education,” Crozier later remembered. “I guess they felt women wouldn’t be that interested in sports.” Nor was much—if any—consideration given to women’s health. Adele Davidson ’75, who would return to teach English at her alma mater, characterized the campus physician from those days as an “old country doctor.” Elizabeth Forman ’73, later a long-time Kenyon admissions officer, said that women who complained of “feminine problems” were given “a form of speed.”

Only belatedly did the faculty move to add women to its own ranks. Part-time female instructors and even some full-time visiting faculty members had appeared at Kenyon during World War II, but none was hired for tenure-track positions. The first female to hold a tenure-track post was Harlene Marley, who joined the drama department in 1969, just in time to greet the College’s first young women.

“There was no concerted policy not to have women. We just weren’t very effective in hiring them,” Dean Edwards later observed, conceding, “Sensitivity to women’s problems would’ve been heightened if we had more women faculty and administrators early on.”

Instead, while vital basics—like the dearth of women’s restrooms on campus—went unaddressed, administrators and students engaged in fierce debates over things like library hours and parietals. Administrators fretted about the sexes mingling in the stacks of Chalmers Library after dark. Even Haywood, perhaps the strongest advocate for bringing women to campus, told the Collegian in 1966, “Two people who are sexually interested in each other cannot study together well.” He proposed barring women from the stacks in the evening. The Coordinate College campus would be furnished with a small reference library for women’s use.

Kenyon’s men, however, had by now warmed to the notion of sharing the Hill with women, advancing proposals in the Senate that would shrink or abolish parietals—the dusk-till-dawn hours when female visitors were generally barred from Kenyon’s dorms. A poll of 503 Kenyon men indicated that more than 80 percent favored allowing women into rooms around the clock. More than once, President Lund stepped in to veto the Senate’s proposals to expand visiting hours.

Indeed, President Lund seemed increasingly weary of the whole mess. Prior to leading Kenyon, he’d overseen the arrival of male students at Alabama College, a women’s school in the South, and he’d once gone on record as saying “an exclusively male (or female) college is an anachronism in today’s world,” but many at Kenyon privately questioned his commitment to the concept of coeducation. French professor Edward Harvey recalled in a letter after Lund’s death that the president “was not keen on the idea.” In his book The Essential College, Haywood claims Lund threatened to block the change at the last minute, inveighing, “I am not going to let that happen.”

Whatever the truth, Lund never got the chance to encounter any young women on Middle Path. In April 1968, exhausted by illness and the fight that led to the closing of Kenyon’s seminary, he announced his intentions to retire that summer.

The women arrived on September 8, 1969. Construction on most of the new dorms was incomplete, so Watson Hall was cleared of men, and many women were lodged with families in Gambier. One young man (an outsider, Crozier alleged) dumped flour on the carpets of the entryway in one new dorm, but otherwise the men were well behaved, according to local media reports on “the Kenyon invasion.”

Ben Gray, a freshman, assured the Painesville Telegraph that the women were “pretty much in demand.” The Columbus Dispatch noted, “Acceptance of the change was very much in evidence Thursday when the girls began arriving.” Scores of men were on hand to greet the “mini-skirted lasses,” carry their trunks, park their cars, and escort them to their rooms.

The women were equally enthusiastic. “I thought it would be exciting to be in the first class of girls at a formerly all-male college,” Lynne Wise of Akron, Ohio, told a reporter. Stephanie Bowman, since deceased, of Silver Spring, Maryland, echoed such sentiments: “I wanted to be in on the ground floor of this new venture and maybe help establish policy.”

One student came from Holland, another from Japan. Others hailed from Texas, Colorado, Louisiana, and Minnesota. But mostly the women in the Class of 1973 were from Ohio, New York, and New England. And like their male counterparts, they were accomplished. Kenyon officials stressed in the Mount Vernon News that the female students “have about the same academic ability as the male students.”

“An awful lot of women were attracted to the idea of establishing traditions and a college,” John Kushan, the head of admissions, later recalled. “We sold the pioneer opportunities very much . . . the first group of women were unusually determined. They had strong feelings of what they wanted from a college.”

Crozier was eager to capitalize on those strong feelings. In an article under the headline, “Crozier Insists on Self-Determination,” the Collegian wrote: “The first class of 175 girls will be pioneers, Miss Crozier noted. She believes the coordinate structure will permit them to establish a separate identity within and in addition to the Kenyon traditions. The emphasis is on independence, not absorption. But Kenyon is to be one community. She plans to stress to the first girls that they can set the life style for the college.”

“It is not my province,” she told the student newspaper, “to be a mother” or to act “in loco parentis.”

Still, Crozier, who never married and had no children of her own, seemed to relish her role as mother hen. She worried about her girls. She looked after them. When necessary, she loaned them her car. “She was gracious and warm,” recalls Tom Edwards. “She loved those women and would’ve done anything in the world for them.” Crozier hosted sherry parties at her home, seeking perhaps not only to entertain but also encourage. “At night,” she later confessed, “I would get in my little Opel to drive around to check on the students at each location.”

She was gracious and warm. She loved those women and would’ve done anything in the world for them."

Tom EdwardsDean of Students, 1957-199

Like all pioneers, the first women faced numerous trials and tests. Predictably, there was harassment by the men—the panty raid on the women’s dorm, the heckling as women navigated the tables in the dining hall (a problem that would persist well beyond the early years of coeducation).

But the women plunged into campus life. They joined their male peers at the Collegian. They sang Palestrina, Schubert, and Britten alongside the men at a concert that first fall. And the winter production of Lysistrata—Aristophanes’ take on the battle of the sexes—benefited considerably from having female talent to draw on. Where traditions and culture didn’t exist at Kenyon, women created their own. A women’s swim team was established in 1970, and the first female lacrosse players trod McBride Field in their first intercollegiate match in May 1971. For a brief while, women ran their own student government apart from the Senate and Student Council.

“I think the women established their identity by proving individual excellence,” Crozier observed. “The men gradually began to accept them.”

I think the women established their identity by proving individual excellence. The men gradually began to accept them."

Doris CrozierDean of the Coordinate College for Women

Not all Kenyon men, of course. Among the most intransigent were some Kenyon faculty members. “There was a great deal of skepticism and condescension that we had to put up with at first,” Caroline Nesbitt ’73 recalled of her professors, answering a questionnaire a decade after graduation. Professors could be openly discriminatory or, just as bad, lowered their expectations.

“The attitude of the professors was sexist and I took advantage of it,” Liesel Friedrich ’73 wrote in the same survey. “‘I didn’t feel well’ or ‘I was too busy with other work to complete an assigned paper’ was easily accepted as an excuse.” There were some unpleasant faculty members, Katherine Dawson ’74 recalled, but their targets were not solely women: men were criticized, too. And professors like Gerrit Roelofs of the English faculty—who, Kenyon historian Tom Stamp ’73 remembers, initially told bawdy jokes in class—eventually grew to respect and appreciate their female students.

Indeed, Kenyon’s “essential culture” changed quickly between 1969 and 1972. “I do think we were a wonderful social education for the men at Kenyon,” Forman says. Male students like Stamp found that interactions with women made them think differently—a transformation that would have been unlikely during Kenyon’s all-male era. Conversations with female friends, for example, ultimately led Stamp to think of himself as “a feminist” and to write his senior thesis on Edith Wharton—a first in an English Department that had never before had a student focus on a female author.

But for many women, such changes were too slow in coming. A good number of the pioneers grew frustrated and left; in fact, less than half of the women who entered Kenyon in 1969 stayed four years. Susan Givens, dean of freshmen in the mid-seventies, encouraged the development of the Hannah More Society to boost retention of female students: female upperclassmen wrote letters to women who had been admitted to the College, urging them to accept, and served as informal mentors to the younger women once they arrived on campus. The idea slowed attrition, and gradually the proportion of women in the student body increased—by 1990, women outnumbered men. (In recent years, the gender breakdown has been about 54 percent women, 46 percent men.)

The first women were also frustrated to discover that many of the College’s traditions remained closed to them. They were barred from signing the Matriculation Book, for example, until 1972. (Since 1983, the book has been available at Reunion Weekend for any women, or men, to sign if they missed the chance earlier.) That same year, female students issued an “Open Letter to the Kenyon College Community” arguing that “a gynecologist . . . should be on campus for at least one day a week.” Women faculty came and went, unable to secure tenure or find comfort in the culture. In 1983, a full decade after Kenyon’s first female students had graduated, an Ad Hoc Committee on Coeducation recommended, among other things, a substantial increase in the number of women trustees and the hiring of at least one woman to a senior administrative post. (Today, fourteen of the College’s forty-two trustees are women, and nearly half of the faculty and staff are female.)

Gender imbalances surely remain. But the original separate-but-equal concept has long since vanished. The Coordinate College was abolished in 1972, under President William G. Caples, with the blessing of the very men who had initially endorsed the concept. In 1971, Haywood lobbied the trustees to officially admit women to Kenyon. “A form which has worked beautifully to accomplish our larger aims is now working against the interests of individual women,” he argued. “We can proudly say that women have a permanent place in this community . . . yet all this will be as naught, if the form that made these possible becomes the source of women’s alienation.”

Caples, who succeeded Lund as president in 1968, was more blunt: “It didn’t take us very long in that first year to find out that the Coordinate College was a gross error,” he said shortly after his retirement. “The women did not feel they were being treated equally. They felt they were second-class citizens. I think to a degree they were correct.”

Oddly, among the last advocates for separation was Crozier, who saw in the Coordinate College a chance for individualism, a new culture on the Hill. The coordinate concept was “an extremely good idea to me instead of mainstreaming girls into a men’s environment,” she argued to the last. The coordinate cocoon had given women a chance to prove themselves at Kenyon—just as it gave Crozier a sense of purpose that vanished when the coordinate school itself did. “The Coordinate College died a natural death,” she recalled in 1979, seven years after she left Gambier. “Thereafter there wasn’t a real role for me here.”

Edwards, who served as dean of students for both men and women at Kenyon after Crozier’s departure, would later view the decision to bring female students to Kenyon as both prescient and short-sighted. “People got swayed into thinking that by building some buildings they were building a new college,” he recalled. But in reality, everything was shared. By the end of 1969, it was clear the Coordinate College idea was “absurd.” Admitting women without diluting the culture was not only impossible, it was undesirable.

“Kenyon wanted to have its cake and eat it too,” Edwards says now. “But bringing women to the College changed the College. Academically, pedagogically, socially, financially—I think Kenyon improved almost any way you measure it.”

Joel Hoekstra is a writer based in Minneapolis.

Top illustration: Doris Crozier, dean of the Coordinate College, is pictured, with a glass of sherry, in this collage with some of the women of the Class of 1973.

An immensely complex transplant operation gives a soldier two new limbs. On the team that made it happen: a husband…

Read The StoryBiochemist and Beatles aficionado, Kenyon's new president grew up with the lessons of learning.

Read The StoryDiscovering Danville's famous raccoon dinner, a Kenyon student muses on socio-culinary boundaries and the people…

Read The Story