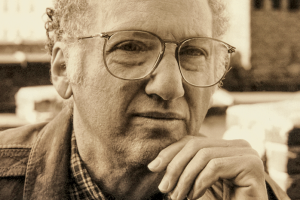

Emily Gould ’03 can’t keep a secret.

“Which is a bummer,” she said. “Like, I really wish that I could.”

Her twenty thousand Twitter followers are not complaining. The thirty-three-year-old author, blogger, and online bookstore owner tweets hourly, divulging her thoughts on everything from the serious (gender inequality; financial struggles) to the not-so-serious (her cat, Swizzle; her obsession with leggings).

Gould’s unapologetic openness about her day-to-day life (sample tweet after sundown: “It’s never too late to leave the house for the first time today”) paired with her sharp-witted observations about pop culture (especially her fondness for Kim Kardashian and Kanye West) have earned her a dedicated following on social media. It’s a responsibility that Gould does not take lightly—most of the time.

“I do violate my cat’s privacy kind of a lot,” she said, mentioning an Instagram photo she recently posted of Swizzle using the litter box. “I think he probably has mixed feelings about that.”

Litter boxes aside, the burgeoning world of social media has become a realm where adept writers can launch careers, mining the raw material of their own lives to attract an audience of readers who identify with them. “Emily’s feed, like most good Twitter feeds, feels like an extension of herself,” said Cooper Fleishman ’09, the New York City bureau chief at the Daily Dot, an online newspaper covering Internet topics. “I’ve always found her writing and tweeting compelling because it feels like a good friend of yours is letting you into her life a little bit, no matter what the topic.”

Gould, who has been letting the public into her life since she started blogging a decade ago, turned her part-time passion into a full-time career when she became a top editor at Gawker in 2006. As the public face for the popular gossip blog, she was accustomed to exposing her personal life and opinions online long before it was commonplace. (At that time, Facebook was still in its infancy, Twitter was just being introduced, and Instagram was nonexistent.)

Eight years later, Gould has parlayed the art of oversharing into an online literary niche, using her influence to support other women writers and earn critical attention for a novel of her own, all while enjoying some celebrity (and notoriety) along the way.

Open for Comment

Gould was twenty-five and working her first desk job as an associate editor at Hyperion Books when she was plucked by Gawker, a blog she had read avidly since its launch just four years earlier. The site revels in celebrity and media-industry gossip along with odd or sensational news tidbits. (Recent headline: “Death, Boobs, and Ice Buckets: What You Googled in 2014.”) During her short but very visible tenure as editor, Gould’s job was to take aggressive, often humorous stabs at the Manhattan media elite. Not surprisingly, her posts drew responses, often nasty ones, from the site’s thousands of daily readers—some directed at what she wrote, others directed at her.

Gould not only read the comments (despite warnings from her predecessors not to), she became addicted to them, craving the instant feedback. In an 8,000-word confessional she later wrote for the New York Times Magazine about the risks of online exposure, she talked about her uneasy relationship with her readers. “They were co-workers, sort of . . . they were fans . . . they were enemies, articulating my worst fears about my limitations. They were the voices in my head. They could be ignored sometimes. Or, if I let them, they could become my whole world.”

The Times Magazine article, titled “Exposed,” sparked what Salon.com called “a firestorm of criticism,” triggering twelve hundred comments—most of them vicious—in less than twenty-four hours, and forcing the comment section to close.

Gould said her decision to leave Gawker—which she fittingly announced in a blog post—was a response not to her critics but to the website’s new business model compensating bloggers based on the number of page views their posts generated. Though her posts already attracted thousands of clicks, sometimes becoming the most-searched Google topics of the day, Gould said she no longer was interested in serving as the public face of an organization that favored sensationalism over quality. She told the New York Times, “You get focused on being sensational and even more brain candyish than Gawker was to start with.”

Today, gossip and news blogs like Gawker scramble to keep up with the rapid-fire pace set by social media platforms like Twitter, which supports 500 million tweets a day. “It felt like things were moving really fast when I blogged professionally, but I can’t even imagine doing it now,” said Gould, who was responsible for twelve daily blog posts at Gawker. “There is so much added pressure to report stories that reflect the enormous pace of things. I mean, I don’t think there’s enough Adderall in the world.”

Metabolism Shift

These days, Gould prefers writing fiction to blogging—calling it a “metabolism shift”—though she occasionally updates her personal blog, Emily Magazine, and chimes in on Salon.com with her takes on feminism, publishing, and pop culture.

“As a writer, Emily’s been trying to experiment with what goes best where—what goes into tweets, what goes into essays, what goes into fiction,” said Keith Gessen, Gould’s husband and co-editor of n+1, a magazine covering literature, politics, and culture. “That’s something writers can and should do, is experiment with all these forms. And across all of them, I think she’s been incredibly brave and very funny.”

Gould’s first novel, Friendship, was the subject of much media fanfare when it was released last summer, garnering press from every major U.S. newspaper and landing Gould in the pages of Elle magazine and on the front of the New York Times Sunday Styles section.

Described by the Times as “sharply observed,” the book (published by Farrar Straus and Giroux) chronicles the longtime friendship between Amy and Bev, thirty-year-old New York City transplants who find themselves at a professional and personal crossroads. Social media also plays a role, both in the characters’ relationship (Gchatting is their communication method of choice) and in their work lives (Amy quits her cushy blogging gig after refusing to star in an online video series that might impede her journalism career).

Incorporating social media was not Gould’s attempt at making a generational statement. “This is just what the characters do,” she said. “It’s how they live their lives, and it would have been weird not to include those details, because that’s how people their age experience the world.” That’s a “really good and awesome thing,” as Gould sees it. “Social media has the power to make it easier for young people to find a community,” she said. “It’s easier to not feel like you’re sitting alone with stuff, to not feel like something happening to you is the first time it’s happened to anyone.”

Gould is especially impressed by young women who have grown up with more access to information that shapes their values, giving them a sense of “real confidence” that she feels she lacked when she was younger. “When I was in middle school, the only way I had any knowledge of feminist pop culture, like Riot Grrrl, or stuff that was really important to me was through the issues of Sassy magazine that I read in the library after school every day,” she said.

Finding Her Platform

As someone who came of age without the influence of social media—Facebook was founded shortly after she graduated from college—Gould does not wish for a return to the days when she was less connected. “It’s easy for me to get nostalgic about stuff like the notebook that my friends and I passed around in high school because I still have it, and I can see our handwriting and I can see how much we’ve changed, and how little we’ve changed,” she said. “But I think everything we’re doing now is such a natural continuation of that.”

Gould spent only two years at Kenyon, but in that time she established herself as an outspoken personality, even without the aid of social media. “From the get-go, it seemed like the entire school was aware of Emily and everyone had strong opinions about her,” said her close friend and roommate Valerie Temple ’03, who met Gould in an introductory art class and was taken by her “wry wit, intelligence, and incredible confidence.” She remembers Gould lighting up allstu, the campus email distribution list then more commonly used for club announcements, with commentary that was only tangentially school-related. “One rant she sent about not getting into a writing seminar was particularly legendary,” Temple said. “As a writer, Emily always has been completely unafraid to put it all out there, and I think she thrives on the feedback she receives, be it praise or criticism.”

Gould left Gambier for New York City the first semester of her junior year to enroll in a Kenyon-approved internship program. She never returned to Kenyon, choosing to stay in the city to earn her creative writing degree at the New School. Her decision to transfer was based in part on her distaste for Kenyon’s social culture, which she stingingly criticized in a memoir, And the Heart Says Whatever, published in 2010. Yet she credits the College with giving her a solid academic foundation and friends, like Temple, whom she still talks to today. “I’m really glad I had both experiences,” she said. “I don’t think I would have wanted to go to New York City when I was seventeen.”

Hitting Refresh

Today, Gould has set her ambitions on promoting the work of other writers through Emily Books, an independent online bookstore she founded with best friend and fellow writer Ruth Curry. Each month, Gould and Curry select a book they feel strongly about from a lesser-known female author and digitally distribute it to their two hundred subscribers. “Emily Books definitely exists to celebrate people’s work that was published a long time ago or maybe even just a couple years ago and didn’t get a fair shake,” she said.

Instead of competing with bookstores that sell large volumes of inventory, the business partners aim to provide a service as “expert curators and trustworthy recommenders.” Their model was commended by the Times for cutting through “the cascade of stories, tweets, links, and other media that flow across our screens every day” to “serve up something reliably good.”

The endeavor is a natural fit for Gould, who often treats her favorite finds like juicy secrets, just waiting to be shared with her online friends and followers. “She’s often the first person to mention books and writers that later become my favorites,” said Rachel Fershleiser, who is responsible for literary outreach at Tumblr.

While Gould is passionate about promoting the careers of fellow authors, she would like to keep writing her own books, particularly in the nonfiction genre. But if Gould’s fans are expecting her next memoir to reveal regrets about the very public path her career has taken, then they don’t understand the writer’s brand of outspoken honesty. “I actually feel like everything that’s ever happened to me has been a result of being truthful about my life, so I’ll probably keep doing it,” she said. “Obviously, there’s been some collateral damage, which is just inevitable, but I’m pretty committed to continuing on this path.”

She did, however, promise to improve her secret-keeping skills. “When I make a Jewish New Year’s resolution, I always resolve not to gossip. Always,” she said. “Who knows? Maybe this is the year.”