The Art (and Industry) of Oversharing

Emily Gould '03 has blogged and tweeted her way to a literary career that reflects the allure and perils of sharing…

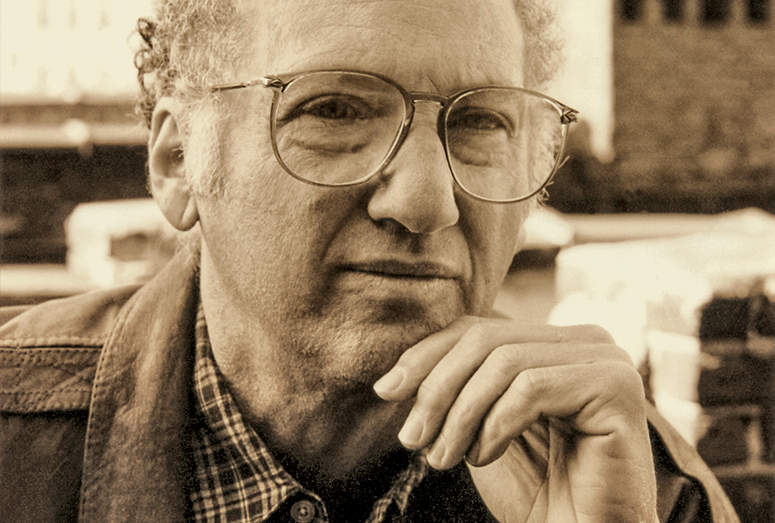

Read The StoryWith the release of his first novel, longtime writer Fred Waitzkin '66 crosses into storied world of fiction.

Despite nearly four decades at the top of his profession, New York City author and journalist Fred Waitzkin ’66 felt something was missing from his resume until the 2014 publication of his first novel, The Dream Merchant (St. Martin’s Press). “From an early age, I thought that the novel is the big-time for a writer. I didn’t feel like I’d be fulfilled until I wrote one,” Waitzkin said.

His novel tells the tale of a morally ambiguous super salesman who, after a series of financial scams, flees to Brazil, where he heads a shady gold-mining operation and falls in love with a younger woman. Waitzkin spent ten years writing the novel, but the wait was worth it: sensational reviews greeted its release. The Dream Merchant followed three nonfiction books and numerous magazine articles in publications such as the New York Times Magazine, Esquire, Forbes, and Sports Illustrated.

Waitzkin is best known for his best-selling 1988 book Searching for Bobby Fischer (Penguin Books), about three years in the life of his chess prodigy son Joshua, an eight-time national chess champion. Five years later, the book became a popular Hollywood film of the same title. “A lot of people might not have heard of me, but they have heard of ‘Searching for Bobby Fischer.’ Saturday Night Live even did a skit about it with Will Ferrell.”

He carved out a chunk of his career in feature journalism by taking readers inside the world of international chess competition. “I knew all the luminaries,” he said. He parlayed his access and insight into Mortal Games (1993, G.P. Putnam’s Sons), a biography of former world chess champion Garry Kasparov, who was played to a draw by Waitzkin’s twelve-year-old son in 1988. “I traveled with Garry for three years. He was a fascinating man and a complete genius, and the time I spent with him was a very rich experience in my life. He lives in New York, and we’re still friendly today,” Waitzkin said.

His other book, The Last Marlin (2000, Viking), a critically acclaimed memoir, recalls his unconventional childhood on Long Island in the ’50s as the son of parents in a loveless marriage. His father Abe was a world-class lighting fixture salesman — “the Beethoven of fluorescents,” Waitzkin says — and his mother Stella was an abstract painter and sculptor totally devoted to her work. “They hated each other,” Waitzkin said. “Somehow I came out in the middle, and both of their impulses are in me.”

Waitzkin knew from an early age that he wanted to be a writer. He planned to enroll at Columbia University until his prep school headmaster steered the English major to Kenyon and its rich literary tradition. His headmaster happened to be a Kenyon graduate. “When I first got to Gambier, I felt isolated, lost, confused, and unhappy. In the final analysis, there was a lot of intellectual intensity at Kenyon that was amplified by so much emptiness all around,” he said.

The young writer earned a master’s degree from New York University and toyed with teaching. As the rejection slips for his short stories piled up, Waitzkin turned to magazine journalism to help support his wife and the couple’s children. “I started doing serious journalism when my son was born thirty-seven years ago,” he said. “I needed to make some money and not be a failed writer. While I was having a difficult time as a young fiction writer, the world opened up to me as a nonfiction writer.”

His work in the nonfiction arena proved to be a great training ground for his first novel because he learned the importance of “plot and place” in order to tell a good story, he says. It is no coincidence that Waitzkin admired the work of “nonfiction novelists” such as Truman Capote and Normal Mailer. Personal experience informs The Dream Merchant. The protagonist, for example, was inspired by his father, and Waitzkin spent a month in the Brazilian Amazon, the setting for the last third of the novel. “If I had not been there and felt it, I could not have made it come alive. I believe all great fiction is rooted in reality,” he said.

Waitzkin lives in Manhattan with his wife, Bonnie, a chess teacher, but when he’s not writing, Waitzkin often can be found in his thirty-seven-year-old boat, deep-sea fishing, a passion he inherited as a youngster from his father and from reading Hemingway. Big-game fishing has been another favorite topic of his writing.

“As I grew older and more mature and settled into my life as a writer, I found that escape to the water was profound and healing. When fishing, I leave behind the ambitions of the city. I don’t worry about the sales of my last book or the essay I have been working on. It just doesn’t matter anymore. I’m watching the birds and feeling the breeze and movement of the water.”

Emily Gould '03 has blogged and tweeted her way to a literary career that reflects the allure and perils of sharing…

Read The StoryGood food on the Hill? Some say it's hard to find — but one writer says there's plenty to love.

Read The StoryWhen Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo López '93 H'07 was imprisoned, a group of media-savvy Kenyon alumni…

Read The Story