Piercing Through the Fog of War

Kenyon alumni and faculty share their thoughts about the power — and the limits — of storytelling in the fog…

Read The StoryThe puzzling past and promising future of one of Kenyon’s most storied buildings.

Story by Carolyn Ten Eyck ‘18 | Photography by Dannie Lane ‘22

I broke into Bexley Hall during finals week of my last semester at Kenyon. A few friends and I climbed in through a window, left cracked open to let in the May evening air.

By that point in the year, ending up in places where I oughtn’t be was something of a habit. I’d written an English thesis on hidden (and not-so-hidden) places at Kenyon, and had crawled and climbed my way into multiple closed-off spaces of campus, including the Old Kenyon belltower and the roof of Ascension.

Most of the places I entered without permission wore their neglect loudly, covered in layers of dust or graveyards of dead mice and insects. As I learned stumbling over half a deer carcass while walking behind the unoccupied Psi U lodge at 2 a.m., death and dust were the best indicators that I was in a space not meant for my presence.

Not Bexley, though. Climbing in through the window and creeping into the large open space of the second floor, we were given the unexpected impression of a welcoming waiting room. No beer cans, no mouse skeletons. The space wasn’t derelict or decrepit. We played Go Fish, did cartwheels, crowded together on the lip of the oriel window for pictures. Eventually, we climbed back out through the window, dispersed to find whatever other wonders awaited in the warm night of early summer.

College buildings — especially on a campus like Kenyon — project a dual sense of tradition and modernity. Beautiful gothic exteriors paired with interiors full of clean, filtered air and eco-friendly toilets. Members of the Kenyon community live and work within the architecture created by past generations of Gambier residents: buildings crafted with an eye toward the future.

Predictions can look quaint and limited in retrospect. They leave the generations that follow with a puzzle: how to take those visions and bring them into the context of today’s realities. Bexley Hall is one such puzzle. A relic of a school that no longer exists (at least not here, but more on that later). An antique too beautiful and history-laden to raze, but too specific to be easily repurposed. It sits on the north end of Middle Path, waiting for reinvention. It won’t have to wait much longer.

In any institution that’s been around as long as Kenyon, misremembered facts and stories are woven into the oral history passed down from senior to first-year, preserved from generation to generation of Kenyon students. Example: Middle Path is a mile long. (It’s closer to ³/5 of a mile.)

Another half-truth? Kenyon originally was founded as a seminary. “That’s not true,” said College Historian and Keeper of Kenyoniana Tom Stamp ’73. “From the very beginning, Phi-lander Chase was envisioning three cooperative institutions: the grammar school, the college and then the seminary, for those graduates of the college who wanted to go on to careers in the church. But the seminary really didn’t exist until Charles Pettit McIlvaine, the second president, came in.” One of McIlvaine’s goals, Stamp explained, was to get the seminary up and running, so he solicited the funds from Nicholas Vansittart in England, who was Lord Bexley, the building’s namesake.

“Bexley was still under construction at the point when Middle Path was installed,” said Stamp. “The first part of Middle Path was [built in] 1842 but the later part, the part that connected from the gates up to Bexley, wasn’t until 1860. But from the very beginning, Chase envisioned Old Kenyon being at one end of the campus and the seminary at the other. So it wasn’t an accident that they ended up being the two termini of Middle Path.”

Both buildings served as tent-pole locations for their respective schools. Both have caught fire, housed generations of Gambier students and been covered in, then stripped of, ivy. But while Old Kenyon remains a social hub, with students streaming in and out of its basement and bulls-eye rooms until late in the night, doing laundry in the basement and smoking outside its side doors, Bexley remains quiet.

Old Kenyon, often cited as one of the first examples of collegiate gothic architecture in the United States, retains its original use as a residence hall and social space for students, and as a prominent visual symbol of the College. Despite being gutted by fire in 1949, its purpose as a space remains the same. Not so with Bexley. Like a less popular sibling, it sits patiently on the edge of campus, unsung and left to its own devices.

Bexley’s building plans came from Henry Roberts, an English architect whose Evangelical leanings often inspired him to design buildings with a philanthropic focus. Bexley Hall is his only building in the United States, and he provided the plans free of charge.

“The instruction is Churchly and conservative, but does not shrink from discussion of those critical questions of the day,” notes the 1910-1911 course catalog from the seminary, which goes on to highlight the area of study:

“Bexley Hall, the home of the Divinity School stands in its own park of several acres. It is a three-story building of pure Elizabethan architecture, erected in 1839, and contains a chapel and recitation rooms, and partly furnished suites of rooms for twenty-four students.”

Not yet a century into its life, Bexley was starting to show its age. A 1913 Collegian article titled “Bexley Hall Scene of Desolate Ruins” paints the familiar picture of the cycle of repair on campus: “The effect of seventy-four years of constant use had been to wear out the interior of the building.”

Years later, another Collegian article reflected on the building’s first major renovation: “The cost has been about $80,000 and the renovated building is stronger, better and more beautiful than the original structure. While only the walls and roof timbers have been retained, the beautiful exterior ... is quite unchanged.”

During the renovations, the seminary students moved temporarily to the middle of Hanna Hall, cohabitating and mingling with Kenyon students. This makeshift move brought new intimacy between the students of both schools, foreshadowing the closeness to come. Together, they played bridge and basketball against Kenyon teams in intramural tournaments, went to parties and attended proms at Gambier’s Harcourt Place boarding school for girls. Once the renovations were complete, the seminary students went back to the new, modernized Bexley.

In 1968, the seminary disassociated with Kenyon and moved to Rochester, New York. There, it affiliated with Colgate Rochester Divinity School (now Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School). Thirty years later, in 1999, Bexley re-established an Ohio campus, partnering with Trinity Lutheran Seminary of Columbus, in the city’s suburb named (what else?) Bexley.

There were several reasons for the move.

As Kenyon’s president at the time, F. Edward Lund, put it, the future of “a little seminary in the woods of Ohio looked pretty bleak.” The rural area did not provide a reasonable training ground for priests who would likely work in suburbs or cities, he noted, and the lack of ecumenism at the Episcopalian seminary was out of step with the “modern church.”

“It is a mark of changing times,” noted a 1967 Collegian article, “that Bexley has taken theological education to the thriving city and left Kenyon behind to carry on its secular education in Gambier’s wooded retreat.”

Space being one of the most highly coveted resources of a college campus, discussion quickly turned toward the future of the building the seminary left behind. It was a period of transition at Kenyon: The women’s college was freshly established, and the selection of a new Kenyon president was underway.

An editor’s note titled, “A Time of Crisis,” from a May 1968 Collegian emphasized the turmoil. “Much must be done to ensure the survival and success of an outstanding college community in Gambier,” wrote the editor. “The vacating of the ample rooms at Bexley Hall provides an opportunity for vast improvement in office space for all organizations.”

And various offices did fill the space, for the next few years. “I remember going to pay my tuition bill at Bexley Hall,” said Stamp. “So the finance offices were there for a couple years.”

Meanwhile, the art department was looking for a new home. Originally, classes in what is now known as the Department of Studio Art were taught in Chase tower of Peirce Hall for extra credit or no credit at all, according to Professor Emeritus of Art Greg Spaid ’69. Once Joe Slate, the founder of the department, arrived, classes moved to the basement of Rosse Hall.

“That’s where I took my first course,” said Spaid. “There was a painting room, and there was a drawing room. They were very small.” The buildings across from the Kenyon College Bookstore on Chase Avenue were also used as art spaces for a few years. But before art students and faculty could move into Bexley in 1972, more renovations had to be made.

“One of the magnificent things about Bexley was this grand staircase that went up the building and that had to be torn out when they had to renovate for the art department to move into it,” said Spaid. “According to code, you couldn’t have wooden stairs.” The ornate wooden pews, ascending in elevation in the tiny Bexley chapel, were also removed to create the photography classroom where Spaid taught.

Associate Professor of Art Read Baldwin ’84 took classes as a student in Bexley Hall

and later, taught there. “I will always feel more attachment to that building than any other on campus. I suppose that speaks to the influence of architecture on youth,” he said. “Everything about the building made housing and creating art a challenge,” he added, citing the unpredictable heating system and tiny classrooms.

When it came to breaking down canvases to relocate them, the small rooms and narrow hallways of Bexley proved slightly less arduous than the staircases of Peirce tower, but they still presented a challenge to the studio art department staff. Thanks in large part to the activism of then-Assistant Professor Terry Schupbach, a lift was installed to make the building marginally more accessible.

“On average, I had twice the number of students than we would currently have in the studio art class,” Spaid said of teaching in the chapel-turned-photography classroom. “I mean, people had to sit on the floor. They had to sit in the windowsills whenever we had a critique, but somehow it worked.”

Many of the professors’ offices were on the first floor of the building. “The darkroom was next door to where my office was. I would get people bringing in their wet, dripping trays with photographs from the darkroom, asking for advice,” Spaid said. “But the proximity worked really well. I could just run in there if anybody had a question.”

Colburn Hall, the old seminary library attached to the back of Bexley by a Tudor arch, became the art gallery, the high ceilings and open space making it the logical place to display the art harbored by the connecting building. However, the lack of accessibility remained an issue. So too did the fact that, simply by virtue of its location, fewer people were likely to stumble in to enjoy the art.

The art department’s new home, Horvitz Hall, was designed by Graham Gund ’63 in collaboration with the art faculty. State-of-the-art ventilation and large, bright classrooms proved a big contrast from the cramped halls and antiquated heating of Bexley Hall. And so, in 2012, studio arts packed up and headed south, to their new building behind Storer Hall. Freshly vacated, Bexley remained on the far north edge of campus, its future once again uncertain.

On a campus always negotiating its real estate, Bexley offered space: A building in search of its purpose, auditioning for different roles. Non-academic offices slowly populated the empty rooms, on and off.

The building was quiet, save for the antiquated HVAC systems struggling to keep pace with the changing seasons.

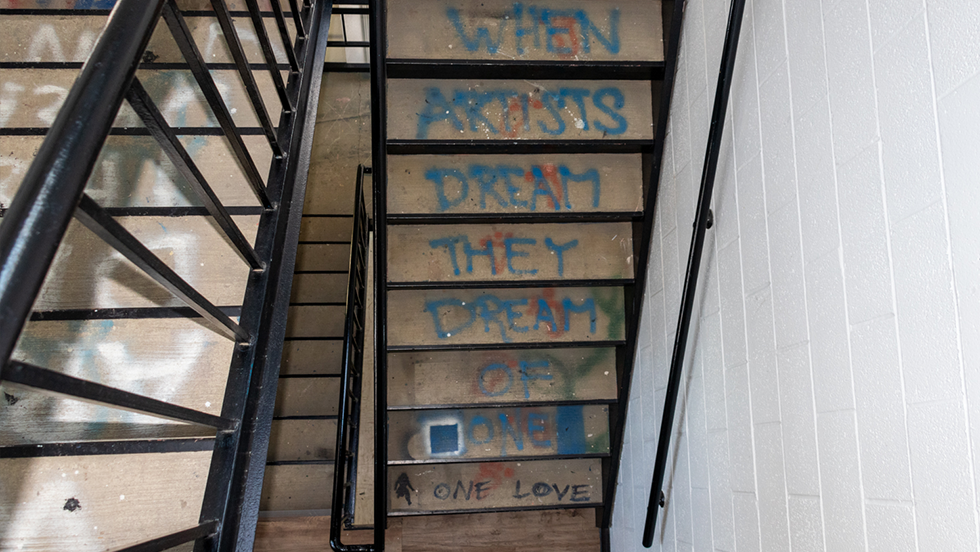

“If you would talk to most students, they’d say that it was spooky,” said retired Instructor of Art Ellen Sheffield. “Because it was this big hulking building with nobody else in it.” After the depart-mental move to Horvitz, she brought her classes to Bexley to use the letterpresses that remained in the lower levels, the walls spray-painted with messages vaunting the power of art.

The abandoned feel of Bexley after dark provoked mixed reactions from Sheffield’s students. “Some of them wanted to explore the building and others were literally shaking, going, ‘No,

I can’t go. Don’t leave me here alone,’” she said. Having inhabited a basement office in the space for years, Sheffield did not share in their hesitation. “The building is filled with good vibes and good spirits, in my opinion.”

Jim Steen, the head swim coach at Kenyon for years, moved into an office in Bexley after he retired from coaching in 2012 but continued his work with the College through public relations and development.

Steen worked in Spaid’s old office, on the ground floor. “I really loved my office in Bexley,” Steen said. “It was quiet and comfortable and somewhat off the grid — perfect for a retired guy who was in the ‘thick of things’ over the previous 36 years.” Until 2017, he used the office sporadically. “There were a few other people with temporary offices in Bexley,” he remembered. “Faculty on sabbatical, various administrators … the building had a nice feel to it, with a small selection of people quietly going about their business.”

All this is not to say that there weren’t plans in the works for the building’s future. A 2004 trustee-approved master plan, helmed by Gund, proposed Bexley’s transition into housing. It also proposed the demolition of Caples Residence Hall, which almost 20 years later still stands proudly above all other buildings in Gambier. Change is slow, until it isn’t.

A housing study completed in 2020 proposed renovations and new builds, including three South Campus residences currently under construction that were funded by a $100 million gift. When a larger-than-expected class led to a housing crunch, Bexley was moved up in the renovation sequence plans after an anonymous donor agreed to pay half the construction costs. Bexley will return to a suite-style living space by August 2023. More inclusive, accessible and eco-friendly housing — no small endeavor.

“It’s a major undertaking,” said Stamp, “but the envelope of the building is in good shape.”

Ceilings lowered in the mid-20th century are being removed, as are the false walls in Colburn. The hope is that the original architectural paneling is still there underneath, in restorable condition. A lot of materials are unusable and will need to be torn out or modernized. But the final look, according to Stamp, will honor the look of the original Bexley Hall.

There’ll be no grand old wooden staircase that defies every fire code ever written, no beautiful-but-inaccessible chapel on the east side, where morning sun must have bathed the tiny pews in gold. But there will be people there, living and working. Students crowding together for pictures and sitting on the floor. Students reading texts both similar and wildly different from the ones studied by seminarians decades earlier. It won’t be quiet anymore.

Before renovations began this spring, the building retained an air of artful neglect. The essentials had been packed up and moved, while the everyday, mundane objects remained. Desk chairs, name badges, loose bags of English breakfast tea. Relics from the studio art department: drop cloths, drawers of letterpress type blocks and graffiti everywhere. In the stairwell: “All Art, No Matter What.” On the stairs to the basement: “When Artists Dream They Dream In Color.” On the basement walls, painted faces, anarchy symbols and crescent moons.

Touring the space years after my late-spring senior escapade, I thought of all the words

I’d seen etched, penned, printed and painted around campus. Names and years scratched into the wood of the Old Kenyon belltower, proof of a successful break-in. Evidence of late-night capers and the desire to prove you were there. These things fade, as they always do: Painted over, knocked down and reimagined anew. But their stories remain just beneath the surface, taking up new residence as half-truths in the grand tradition of Kenyon lore.

Kenyon alumni and faculty share their thoughts about the power — and the limits — of storytelling in the fog…

Read The StoryDavid Bukszpan ’02 talks writing, puzzling and his published New York Times crossword.

Read The Story