Five Reasons To Care About Kenyon 2020

The College's strategic plan is more than a play on perfect vision. It's the future. And it starts now.

Read The StoryDuring the golden age of illustration, Coles Phillips, Class of 1905, conjured a vision of American womanhood.

Story by Rose Shilling

Neal Mayer ’63 H’07 and his wife, Jane, are collectors of art — nothing too fancy, just items they enjoy. They’ve filled a curio cabinet with about a hundred decorative turtles and own a lot of pottery, Jane’s medium as an artist.

In the early 1980s, on her regular visits to flea markets and antique fairs, Jane started finding early-1900s Life magazine covers of pretty women whose dresses blended with same-colored backgrounds. Neal, a partner in a Washington, D.C., maritime law firm, searched online for more covers by the artist: Coles Phillips.

The couple framed a dozen favorites and hung them in a bathroom of their Millsboro, Delaware, home.

“We’re fascinated by people’s imaginations, and if we see something we like, we collect it,” Jane Mayer said. Her husband added, “We like to be around things that make us smile.”

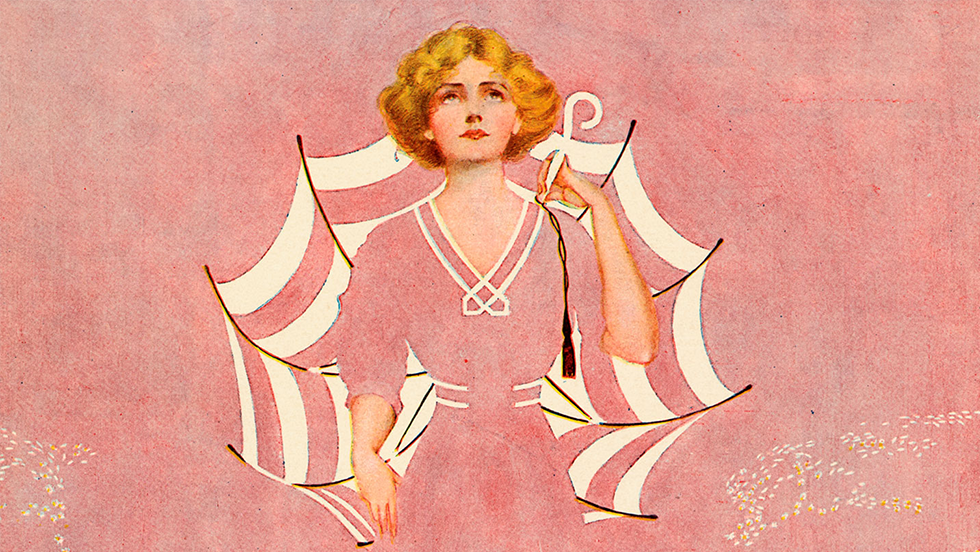

Vintage poster dealer Jack Wood, a member of the Class of 1975 who transferred after a few semesters to Vanderbilt University, similarly started picking up posters and magazine covers by Phillips. The artist illustrated extensively for Good Housekeeping, Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post as well as Life (a humor and entertainment magazine at the time, Life wouldn’t devote itself to photojournalism until the 1930s). He often depicted idealized, sometimes seductive, pink-cheeked women playing traditional roles or trying to choose among suitors.

And he had a distinctive, intriguing style. Despite the fact that he didn’t paint the outline of the woman’s dress against a matching background, viewers could easily make out her form.

The two men don’t remember when exactly they figured out that the illustrator of these female figures —dubbed “fade-away girls”— was also a Kenyon man. Phillips was a member of the Class of 1905.

“I got really interested in him after I knew he was connected to Kenyon because I’m so damn connected to it,” said Neal Mayer, who served on the Kenyon College Board of Trustees for seven years starting in 1995.

The link sent both men hunting for more work by Phillips, whose advertisements and magazine covers became so popular in his time that he often scheduled work a year in advance. When publishers didn’t have a Phillips cover, they would request work with his fade-away style. The women he painted increased sales of cars, silverware, hosiery and bathing suits.

“A lot of the nice double-page ads that he did, they’re almost like centerfolds. They’re beautiful,” Wood said. Young men would swipe his posters from stores or cut pictures from magazines and hang them in their college dorm rooms.

“From the time of his first color covers for Life until his death, Phillips was as well known as any of his contemporary illustrators,” said Norman Platnick, a collector who has cataloged illustrators’ work in 21 guides, including one about Phillips. “His work was hugely sought after, especially for advertising pieces.”

The fade-away girl did not enjoy the enduring fame of the Gibson Girl or the scenes of everyday life by Phillips’ friend Norman Rockwell. But Phillips’ career lasted only 20 years. He died in 1927 at age 47, when he thought he was just getting started as an artist. In 1993, he was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame.

A biographical sketch in A Young Man’s Fancy, one of two compilations of paintings that he produced, notes the whimsy of his work. “The Coles Phillips Girl typifies the subtle charm of American womanhood. In the drawing-room or in the kitchen, breaking hearts or baking pies, or outdoors, always alluring, always at home, a real woman from the tip of her dainty boot to the soft glory of her hair ...”

Born Clarence Coles Phillips, the artist grew up in Springfield, Ohio. As a boy, he sketched animals and caricatures of friends, according to an out-of-print book about him, All-American Girl. He enrolled at Kenyon after his boss at a radiator company said he wasn’t suited for a job in business.

Phillips attended Kenyon for three years and was a member of Alpha Delta Phi before leaving to seek work in New York City. He contributed illustrations to several editions of Reveille, the yearbook, including a picture — for the fraternities section — showing a dozen dapper men walking in rows of four on Middle Path. In the 1914 Reveille, the “society” section opens with a girl wearing a purple dress that Phillips had sent back to his alma mater.

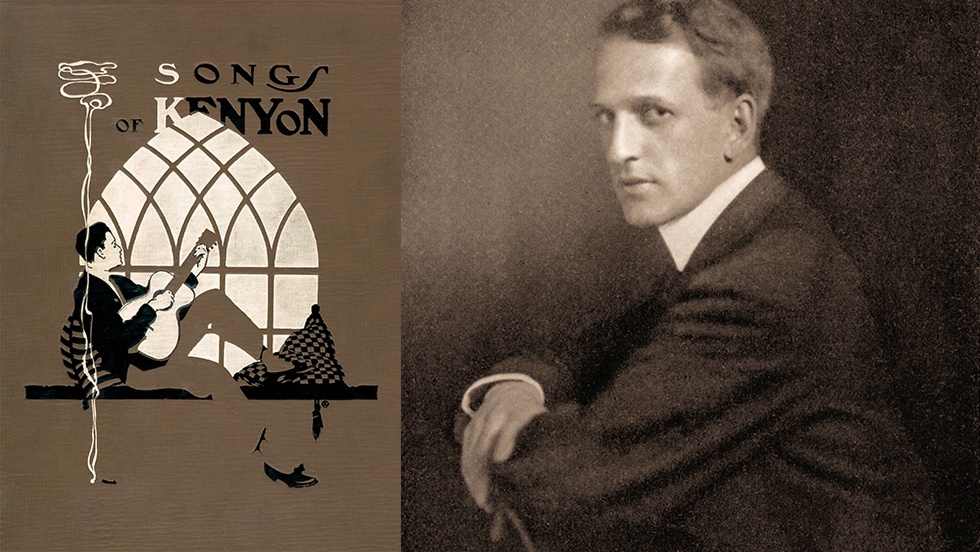

Phillips also did the cover for the 1908 book Songs of Kenyon. The picture, which hints at the fade-away technique, shows a man in a suit gazing out of what appears to be an Old Kenyon window.

After leaving the College, Phillips (called Psi by friends) lived among other former Kenyon students in New Rochelle, outside New York City. The town attracted other illustrators as well, including Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker.

He worked briefly for a studio that created catalog images in assembly-line fashion, with the illustrators sitting at a long table, each drawing a single part of the picture, over and over. Phillips often drew the feet, good practice for an artist who would eventually conjure many a shapely ankle. An art school night class and some watercolor courses during this time were his only formal training.

He went on to work for a large advertising agency and briefly ran his own agency. In 1907, needing a sale to pay his studio rent, Phillips took a cartoon to Life. According to his biographers, he was told the editor was not seeing sketches that day, and the secretary asked if he wanted to leave the carefully wrapped drawing. He did not, but he eventually got a meeting with the editor and left with a check for $150 for the piece. He worked with Life for the remaining 20 years of his career.

That career unfolded during what historians consider the golden age of illustration. Great improvements in printing technology made color illustrations affordable, said Austin Porter, a postdoctoral fellow at Kenyon’s Center for the Study of American Democracy who teaches about the relationships between art, politics and culture.

The stylishness of Phillips’ work reflected the spirit of the dawning Jazz Age, according to Porter. “Whereas someone like Norman Rockwell is much more associated with sentimental scenes, Phillips had a more contemporary look — in the dress and objects his subjects were associated with — that also often featured sexualized female figures.”

Today, Phillips’ work can be found in collections both public and private. The National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island, has eight of his pieces. Kenyon’s holdings in the Greenslade Special Collections and Archives of the library include a portfolio of 25 advertisements, among them ads for Holeproof Hosiery and L’Aiglon Daytime Frocks & Slipovers.

The Mayers own about 35 magazine covers, several rare books of Phillips’ work and a postage stamp of one of his hosiery advertisements, part of a set dedicated to American illustrators. They never paid more than $35 for a magazine cover.

Prices can go much higher. Wood, who left his career as a stockbroker to pursue a passion for vintage posters, sells Phillips pieces in the Jack Wood Gallery, located in a trendy neighborhood in downtown Cincinnati. There, mounted magazine covers by Phillips typically cost $100. On the other hand, a poster-size ad for Luxite Hosiery is priced at $2,400.

Phillips also has a place in Wood’s impressive personal collection, which includes pieces by masters Alphonse Mucha and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Wood displays a copy of Songs of Kenyon on his piano. He also owns a remarkable Phillips poster showing a bare light bulb with a floral motif in the background — it was done for the government during World War I, as part of a campaign urging people to save coal by conserving light.

“It’s a striking image, and it’s somewhat rare,” Wood said. “For World War I poster collectors, that’s a very desirable image.” He once sold a different copy of the light-bulb poster for more than $8,000 through a New York City auction house.

Original watercolors by Phillips have gone for $5,000 to $20,000, with some bringing in more, according to Platnick, the catalog author. Platnick has a large collection of Phillips’ work.

Originals are rare. Many artists did not care about keeping originals once they were paid, according to historians. Some originals likely were given away as gifts, taken during office moves, lost or stored in archives.

Phillips will be remembered for his artistry, but he devoted himself to another unusual pursuit: racing carrier pigeons. For his eighth birthday he requested the birds, and he was allowed to buy three, for ten cents apiece. “No possession I have ever had since has given me so much pleasure,” he wrote in an article for the Saturday Evening Post, published days before his death.

Two babies hatched, one pure white, one blue. “You fellows who have sold your first painting or story, or bought your first car, don’t know what a real thrill is,” he wrote.

The “athletes of the bird world” could fly 500 to 600 miles per day in daylight, if properly trained, he said. Later, his pigeon farm had a yearly output of 30,000 birds, some of which aided soldiers in World War I.

Phillips, who also sang in a glee club and in quartets as an adult, met his wife, Teresa, one of his most frequent models, by approaching her outside the hospital where she was a nurse to ask her to pose for a picture. They had four children.

During his working years, he judged college beauty contests from photographs mailed to him, but his wife said the frequent requests became a nuisance and he had to turn them down. He did choose Kenyon’s homecoming queen for years, according to his biographer.

With tuberculosis bacteria infecting his kidneys, he was ill in the last years of his life and told his wife that he would start a new phase of his career when he recovered. In an article published after his death, she wrote: “He had definitely finished with drawing pretty girls.”

How does a Phillips girl fade away?

When you look at a Phillips fade-away girl, your mind has to fill in the outlines of her form, because the color of the clothing matches the background.

Phillips, who worked in gouache opaque watercolors, did not paint all the edges of a woman’s dress. But the viewer easily can discern her shape with the help of other details, such as her hands, a row of buttons or a line of lace trim.

The idea for the fade-away technique came to Phillips one evening when he watched a friend, who was dressed in black, play violin in dim light. The musician’s figure was suggested only by highlights on the instrument, patent-leather shoes, white shirt front and cuffs, according to an article by the artist’s wife, Teresa Hyde Phillips.

She said the technique took careful planning. “If the anatomy was not practically perfect, the illusion was destroyed,” she wrote.

Phillips apparently dabbled with the technique early in his career. In the cover illustration for the 1908 book Songs of Kenyon, for example, the pant leg of the guitarist disappears into the brown background

and is distinguishable because of shadowing around the ankle.

The striking effect of the technique is what attracted collector Jane Mayer when she saw her first Phillips’ magazine cover. “I looked at it, and I was totally, totally intrigued about how he did it. You can see the outlines of his art, but they’re not there,” she said. Her husband, Neal Mayer ’63 H’07, was equally impressed: “What he did was incredibly ingenious, the idea that the picture and background are connected in a way that you have to figure out where the borders are.”

The College's strategic plan is more than a play on perfect vision. It's the future. And it starts now.

Read The StoryCity papers are dying and you can't always trust the Internet, but Kenyon journalists embrace the challenge of…

Read The StoryPatti Paige '74 turns sweets into artwork - including a miniature version of Rosse Hall in gingerbread.

Read The Story