They were pioneers. They were intrepid explorers in a strange, new world. And, sometimes, they were Amazons. At least that's how it seemed to me when I looked up to them, the first students to enroll at the Coordinate College for Women at Kenyon College. But talking a quarter-century later to women who entered Kenyon in 1969, I realized they had no hidden agendas, no special coping skills (or mythic proportions); they were just seeking a good education at a small Midwestern liberal-arts college. As freshman, they didn't march up the Hill, fiery-eyed, to take things over. To hear them tell it, they arrived quietly, in station wagons, just like the men, just as nervous, more concerned with grades and roommates than with power.

In 1995, they don't seem to want to cast themselves as heroes, but, no matter what they say, it took a hell of a nerve to gatecrash "The Kenyon Experience" in 1969. Their courage changed this place and made it a lot easier — and more bountiful — for those of us who followed, women and men.

In the intervening twenty-five years, the alumnae collectively known as the Women's Class of 1973 have pursued diverse career and life choices, in law and art, medicine and education, rearing children and living lives of quiet inspiration.

It's difficult now to categorize them as a homogeneous group; it's far more interesting to know them as individual women.

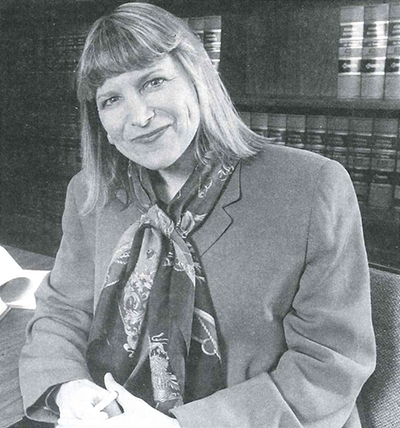

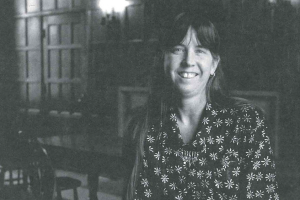

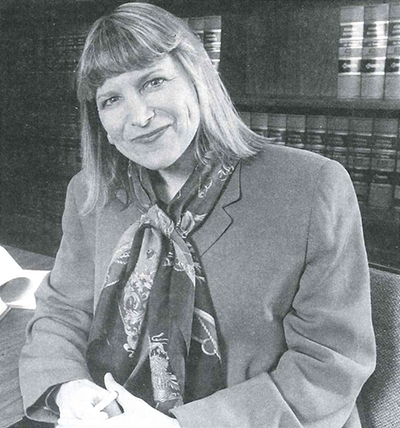

Patti Eanet Dratch

When Patricia Eanet Dratch was considering college, she looked at several large, urban institutions but found she was drawn to the smaller, "idyllic" setting of Kenyon. So the Washington, D.C., native found herself in Gambier in September 1969 with the 174 other women who were about to begin the adventure of creating the Coordinate College.

While studying in the political science department, from which she went on to graduate cum laude, Dratch engaged in philosophical debates with Harry Clor, who encouraged her to think of fa.w school. She continued her studies at the Columbus School of Law at Catholic University, where she was most intrigued by her criminal and labor law classes. Following those interests, Dratch spent her second and third years of law school clerking for the United Mine Workers Pension Fund and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). When she graduated in 1976, she took a position on the staff of an NLRB judge, writing judicial opinions for the board. But Dratch says she preferred using the law as a way of interacting with people and effecting changes, not as a theoretical exercise.

Dratch then moved to the Federal Home Loan Bank Board for a brief period before landing a long-term position with the Federal Labor Relations Authority, where her responsibilities were the investigation and litigation of statute violations. She says she enjoyed investigation, meeting the people involved and exploring all sides of their disputes, attempting to settle cases rather than bring them to arbitration or trial.

In 1989, Dratch joined the Office of Chief Counsel of the Internal Revenue Service, part of the Treasury Department. She laughingly admits that she always has to explain that she doesn't have anything to do with taxes; rather, she is an attorney for the federal government, working primarily in discrimination suits at the national level. She represents the government in cases in which federal employees bring charges of discrimination against their agencies.

It is Dratch's sense that very few of these complaints cannot be settled by impartial examination of the situations, so her investigations focus on whether discrimination exists or if there is justifiable cause for the action, e.g., whether an individual has been passed over for promotion because she is a member of a minority or because she has a less-than-exemplary work record. Dratch believes she has been particularly successful in the position because of her prior experience with, and consequent understanding of, labor unions.

In addition to her progress in labor-relations law, Dratch has negotiated the complex task of raising a family. Already a single parent to her twelve-year-old son, Sam, for the past seven years, she is anticipating an expanded family when she remarries in May.

When Sam was young and suffering from several health problems, Dratch says she was fortunate to have the independent responsibilities of her job at the Federal Labor Relations Authority — and the seniority — to allow for a flexible work schedule. She could arrange her investigation schedule and office time so that they didn't conflict with Sam's needs, and her extended family network in Washington could help out when necessary.

But taking time out for a child meant that Dratch missed some of the coveted overseas assignments available to lawyers investigating cases on military bases around the world. As someone who had spent a high-school summer on a kibbutz in Israel and who had taken a junior year in England, she recalls that this was something of a sacrifice. But now that Sam is healthy and well-adjusted and she is pleased with her situation at the IRS, Dratch says it has all worked out for the best.

So, while Dratch says she didn't consider herself a pioneer at Kenyon, in many ways she has been in the vanguard of women who have successfully managed to combine a career with a family, without losing perspective — or a sense of humor.

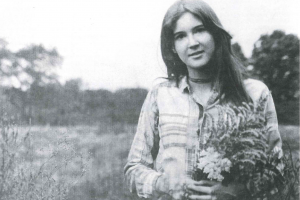

Barbara Lee Johnson

When the distaff members of the Class of 1973 arrived on campus, the dormitory in which they would reside wasn't yet ready. So some of the took up lodgings in Alumni House, where many forged close bonds amid the homey atmosphere and cranky plumbing. Patty Eanet's roommate was one Barbara Lee, a particular standout because there were only size students of color in the entire class.

Barbara Lee, now Barbara Lee Johnson, arrived at the College from Gary, Indiana, expecting to be "the great American actress." But, while that didn't happen, she says she was glad to have "the good fortune to go through the Kenyon experience, learning to think and learning to view the world in different ways. It taught me to live in and adapt to an ever-changing world."

As one of only three African-American women in the Class of 1973, Johnson says she believed she had a responsibility "to be a Black Woman in the first class of women, not just another student." That, of course, was in addition to all the other attendant worries of being a student, from adjusting to college life, to finding scholarship support, to meeting parental expectations. And, after junior year, she became a wife, marrying classmate Johnnie Johnson and moving into the Norton Hall apartment.

As a cum laude graduate with high honors in English, Johnson says she had little difficulty finding a job after graduation, if only because she could read and write better than the average prospective employee. She began working as a systems analyst with Allstate Insurance, writing manuals for the company. In 1977, the Johnsons decided to have a baby, and Barbara, having thought about teaching as a career because the schedule and career goals were compatible with raising a family, decided to enter graduate school at Indiana University to obtain her master's degree in English education.

Johnson, who began teaching English in 1980, says she felt "a harmony and compatibility of the soul in the field," finding her job challenging, "at times frustrating," but ultimately fulfilling.

Since 1988, Johnson has been teaching tenth- and twelfth-grade classes in the DeKalb County, Georgia, schools. Her current school, Henderson High, provides its students with a much more multicultural environment than her own schools did, with a student body that is 45 percent African-American, 43 percent white, and 12 percent Asian-American and Latino.

In addition to teaching English, Johnson coordinates a program of "writing across the curriculum" and does some college counseling, encouraging her students to think about postsecondary opportunities and to participate in scholarship contests. She counts her service as coach for these academic competitions among her most rewarding efforts, and it's easy to see why. In the first year of the "Share the Dream" program, an essay competition for scholarships sponsored by the CocaCola Company, one of Johnson's students won both the national contest and a college scholarship worth $15,000. Johnson has since coached another successful state applicant.

Intermingled with her teaching, the Johnsons have found time to have three more children. The Johnson childrenWilliam, Rachel, Garrett, and Kamillenow range in age from seven to seventeen, and Barbara knows the challenge of juggling six busy lives. "You can't know how much responsibility and time a family takes until you have one," she notes, looking back on her expectations following the birth of their first child. "I chose to put my family first, followed by my teaching, and I just had to cut away what wasn't important."

Her success both inside and outside the classroom, with pedagogical methods as well as personal interaction, led to Johnson's election as Teacher of the Year at Henderson High in 1992. She was also recently selected by the Henderson student with the highest SAT scores as the teacher who most influenced his success, "The Star Teacher."

With all the responsibilities for her own family and her school family, Johnson is also helping plan the celebration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Black Student Union (BSU) at Kenyon. Repeating the pattern of a quarter-century earlier, she is the only female on the committee. But that doesn't diminish the pride and satisfaction Johnson feels now in seeing many of the programs begun under the auspices of the BSU still going strong and providing a sturdy foundation for today's students of color at the College.

Robi Artman-Hodge

Carole "Robi" Artman-Hodge took a circuitous route to her present situation. She came to Kenyon from her hometown of Painesville, Ohio, seeking a well-rounded education through a curriculum that was science-oriented but also had a "human" side of academic inquiry.

"On one side of Middle Path, I was encouraged to write Faulknerian paragraphs, and on the other side I was handed back my lab reports and told to write the results succinctly," she remembers. "What I learned best at Kenyon were thought processes."

Artman-Hodge says she thought most of her fellow male students were "halfway between juvenile delinquents and ministers," although, as a female in a formerly male institution, she found Kenyon "small, but forgiving."

Originally motivated to develop a career in some aspect of chemistry, as she progressed through the College she found that Kenyon did not offer much career assistance or encouragement to graduating serniors. In an era when many students were "dropping out to find themselves," this seemed a critical lack to Artman-Hodge. She recalls that Professor Gordon Johnson sent some of his chemistry students to a consultant in Columbus, Ohio, to compensate. However, when Artman-Hodge went to her interview, she was told "not to expect much as a woman in the sciences."

Instead, Artman-Hodge entered the Peace Corps after graduation. She says she had always been drawn to Africa, and she could teach chemistry there. So, from 1973 until 1975, she was posted to Zaire as a teacher of chemistry, biology, and physical education. During this time, she discovered that her interest in studying chemistry did not automatically translate into a love of teaching chemistry. While she had enjoyed working out formulas and seeing prompt results from her work, she decided that waiting to see if a student could develop into a chemist was too long a prospect.

When Artman-Hodge returned to the United States, she became a recruiter for the Peace Corps for two years, first running the Cleveland office and then moving to Chicago to work out of the regional district office. It was during this time that she became disenchanted with a government job because of frustration with bureaucratic delays and lack of results. At a personal crossroads in the winter of 1976, she thought of continuing her chemistry studies to acquire a Ph.D., but the career prospects were more in the arena of management than lab work, which, she knew by then, was incompatible with her personality.

So Artman-Hodge began working for Harris Trust and Savings Bank to make ends meet while studying for an M.B.A. at the University of Chicago. As a trainee in the area of commodities and transportation, she discovered a "joy in math and an aptitude for commodities trading." Completing her degree in 1979, she transferred to the Harris Bank International Corporation in New York City to become a lending officer with responsibilities as an advisor to commodities companies.

As she learned more about the field, Artman-Hodge says she understood the processes involved in the commercial exchanges and the consequences of her actions and advice. It was a satisfying approach, with tangible results. In 1981, she joined Banque Paribas in the field of commodity financing, primarily in the areas of metals and energy resources. Her duties ranged from assessing options to advising on foreign-exchange and interest rates. It was here that ArtmanHodge became involved in establishing a division of the bank as a futures commission merchant, dealing with the purchase and sale of futures on commodities exchanges.

In 1989, Artman-Hodge moved to a Dutch bank, ING Capital, where she is now a managing director. She deals with fungible goods, collections of more or less interchangeable items that can achieve a common price for a common quality despite the disparity of the individual lots. One of her responsibilities is risk-management advising for natural-resource companies involved in mining precious metals and in exploring energy resources, such as oil wells. Through her financial acumen and understanding of the products, Artman-Hodge assures that these companies will have sufficient profit margins to continue to be able to acquire new resources to replace their expendable products.

So how does this fit in with the career ambitions of a chemistry major of twenty years ago? "I have to know the products in order to be able to hedge against price risks, so I'm still looking at applied chemistry or geological sciences. The companies are still using the basic processes I learned at Kenyon, although the technology is much advanced, of course."

Artman-Hodge, who married classmate James Hodge in 1977, believes she has integrated her work life and her personal life, although she admits that having a family and a career requires "compartmentalization." The mother of elevenyear-old Timothy and eight-year-old Krystn, she finds herself supplementing her children's education with science projects at home.

When they work on something together, Artman-Hodge can often relate the process or the product to one of her former employers. That's when the children see their mother as a professional advisor as well as a fun playmate.

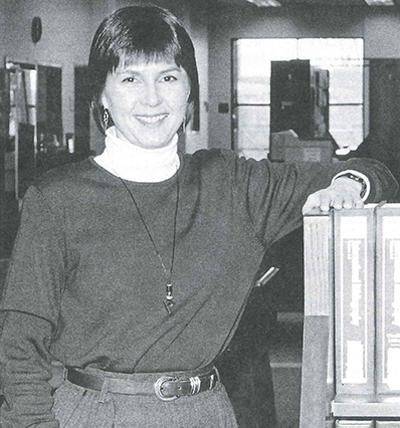

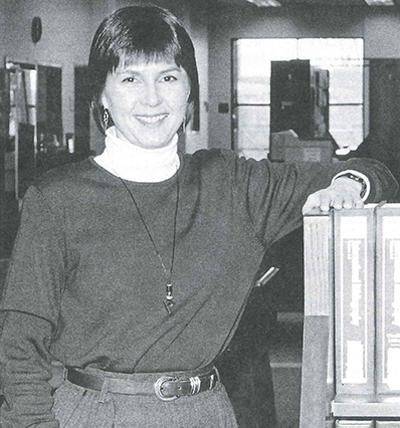

Carol Eyler

"I think it's rather ironic," observes Carol E. Eyler, "that I went to a men's school but am now in a predominantly female profession."

In another way, though, Eyler's years at Kenyon go a long way toward explaining her career as a librarian. Her immersion in the liberal arts, she explains, caused her to value the joy of roaming the intellectual countryside, of being a dilettante, a word she interprets as positive.

"I asked myself what could keep me in that milieu," she says, "and realized that being a librarian is a good way to know a lot of things."

Without ever having visited the College ("Kenyon wasn't even on my short list"), Eyler finally applied and received a good scholarship offer. Before making her first trip to Gambier, she decided, "Unless I hate the place, this is where I'm going." Then, as a student, she never wanted to leave Kenyon, even for the summer, and sometimes didn't. Eighteen years later, the reluctant freshman was elected president of the Alumni Council.

Now head of technical services and systems at the Mercer University library in Macon, Georgia, Eyler looks back to a "very lucky" time at the College, and a time for undergraduates generally, when "you didn't worry at all about what you were going to do. You figured you would go to graduate or professional school or graduate from college and progress through a series of jobs." In her exploration, Eyler changed majors three times, graduating cum laude in history.

During her senior year, when her parents started asking questions about her life plans, "I spent time thinking about which discipline was central to me," Eyler says, "I made diagrams, drew pictures." And she decided that, even though she didn't know any librarians personally and "knew next to nothing about what the work would involve," she would head in that professional direction and earn an advanced degree. It wasn't so much the proximity to books themselves that drew her to library science; it was more "the idea of an academic setting, where I would need a broad familiarity with ideas, names, and so forth."

One graduate degree ( the University of Pittsburgh) and four libraries later, Eyler has shown a determination to abide by and enjoy her decision.

Five years after finishing graduate school and taking an internship at Chatham College in Pittsburgh, she had advanced to the position of head librarian at the small, private liberal-arts college for women. It was an environment she enjoyed, but, after almost nine years at Chatham, she decided to look for additional challenges at a larger institution. For the next four years, as acquisitions librarian at James Madison University, Eyler oversaw an annual budget of $750,000, while serving in a tenure-track faculty position.

In 1989, however, she was offered the prestigious Mellon Internship for Preservation Administration. She left Harrisonburg, Virginia, for Ann Arbor, and the University of Michigan, to study preservation techniques-the general care of collections, she emphasizes, not conservation of special items. The skills she acquired there appear within a list of her professional presentations-working with Habitat for Humanity on preserving archival materials, for instance, or consulting with the Southern Baptist Library Association on "Will the Bindings be Unbroken?"

Of all she learned at Michigan, though, what directed her most emphatically was that "I wanted no part of a research library."

Since making that decision, Eyler has managed technical services at Mercer, a small university of fewer than seven thousand students. "It's all behind the scenes," she explains, "acquiring, paying for, cataloging, physically processing, and, more and more, operating various online systems." Technical services is the direction her jobs have led over the years, and Eyler has some regret that her role allows for little public contact.

But she likes her job and she likes her life in Macon, where she lives "almost in the country" with a front yard offering "scraggly wild stuff, raccoons, and birds." Atlanta, where she attends weekly rehearsals of her women's chorus, is eighty miles away. "I don't have a shred," says the Lima, Ohio, native, "of wanting to live there."

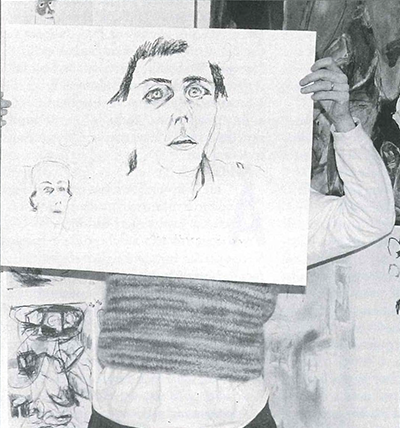

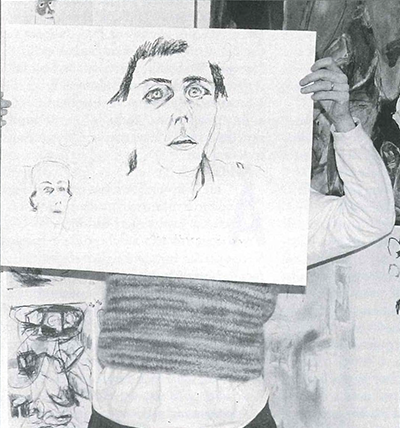

Ann Wiester Starr

Ann Wiester Starr was one of the those who wrote the constitution that brought the men and women together as a single student body at Kenyon. An honors English major, she recalls herself as "the most horrendous grind" because of her studious intensity. Yet the Mount Vernon, Ohio, native feels her Kenyon education was "like being exposed to light and air: the freedom to study and the opening of an intellectual world." It laid the foundation for Starr's next twenty-five years.

After graduating magna cum laude in 1973, Starr says she entered graduate school in English at the University of Virginia "because of a lack of initiative in trying new things. But graduate school was horrible because it was so limited. Many of my classmates were intellectually timid and did not use the experience to expand their horizons."

Graduate school, says Starr, taught her that people are limited by what they excel in, not by what they do poorly. It's her theory that when you discover a talent, you tend to repeat your efforts in that area rather than stretching into a new area in which you may not have such polished skills or as much aptitude.

Earning her master's degree in 1975, Starr began teaching in a private parochial school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She discovered that, while she enjoyed learning, she did not enjoy teaching. She then went to work in the Princeton University library as a researcher, but she found that she didn't enjoy that, either.

Starr next moved to graduate school at Princeton, where she served as director of graduate admissions and cultivated a long-standing interest in minority education. While there, she formed a consortium of fellow officers from Ivy League institutions committed to developing a program of regional conferences in the arts and sciences that would attract the target minority undergraduates into graduate programs at those same institutions.

Soon after, Starr left Princeton to manage an independent program to develop a pool of minority undergraduates who would proceed to graduate school and enter a mentoring environment once they arrived there. She wrote grant proposals that resulted in federal funding for the program, which came to be headquartered at Harvard University.

Proud of the success of the program, which in one year provided 10 percent of the participant institutions' newly enrolling minority students, Starr applied to — and was accepted by — the School of Organization and Management (SOM) at Yale University to study public and private management. She contemplated working toward a degree in nonprofit management, but she dropped out of SOM after realizing that she disliked the narrow focus of the classes and the program.

Starr found herself trying her hand at creative writing and raising a family with her husband, Ray Starr '75, by then a faculty member in classics at Wellesley College. Although she had begun work at the National Consumer Law Center in 1984, she discovered that after eighteen months she was writing the same proposals over and over, and she grew bored and unchallenged.

Mindful of her theory that one is hampered by one's successes, Starr left the job and turned to being a full-time, at-home mother. She felt her first daughter, Maggie, "was quite an interesting person by that point," and she wanted to be more closely engaged in her development.

In 1987, when Maggie was three, Lizzie arrived to complete the family. Starr audited some drawing classes at Wellesley and immediately took to the creative outlet art afforded her. Now her art is primarily painting, usually large, abstract, multimedia pieces. Her paintings are explorations — "frightening, emotional work," she says — that she then refines in subsequent drawings.

Starr says she finds this form of painting a way to concentrate and a way not to repeat things she already knows about: "Every day is different." While she is not currently represented by a particular gallery, she doesn't worry about selling her works. "At first, I was defensive about being out of the professional mainstream, but I have shown extensively and I do participate in residencies in artists' colonies." These retreats, she says, are "an orgy of work and pure pleasure. They are like my freshman year at Kenyon, when I worked so hard but with pure delight. There are no distractions, and there is lots of psychic space in which to concentrate on work."

Starr's early paintings were explicit breaks from the control that words and writing had exerted over her life. Through the last few years, she has expanded her media to include very small, handmade books, in which she creates both the pen-and-ink illustrations and the handwritten text.

"Now words and art are synthesized into an extremely potent combination for me," Starr says. "My verbal life is now enriched and supported by my visual work. A fascinating part of this is that my goals are now all interior. I have been able to divorce myself from exterior goals and what 'success' means as a woman.

"My art is 'feminist' only because I am female, not because of a political agenda. I want my children to see their mother living an integrated life: the art making, the intellectual activity, and the mother;ing are all independent from any professional environment."

Alice Straus '75, a member of the Contributing Writers Group of the Bulletin, is the donor relations officer at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin, where she lives with her husband, Kim Straus '76.

After Alice Straus arrived as a student at Kenyon from the Washington, D.C., area, she began to realize what she'd missed as a U.S. Navy child, moving every few years: a sense of community. "Until Gambier," she says, "I never had a consistent group of people around me."

In the early seventies, when the College was significantly smaller than now, she found herself in a community where, she recalls, administrators would use the campus to play hide-and-seek. She remembers Dean of Students Tom Edwards and some of his colleagues hiding from Director of Admissions John Kushan in the upside-down tree near the chapel.

After graduation, Straus moved back to Washington as a computer-systems analyst with the Veterans Administration, but she stayed close to her alma mater, especially through activity with the alumni association. In 1979, thought, she made the move back to Gambier and took on a series of positions with the College that would form a Kenyon career. Except for a year away in New Mexico, she was called on to accept jobs throughout the campus as secretary, special assistant to the president, assistant director of development and of admissions, acting director of the Faculty Resource Center, and assistant to the news director.

Now serving on the Alumni Council and as a frequent contributor to the Bulletin, Straus continues to visit Kenyon. It's a place, she finds, where she has a chance to sit down with "normal" people — those who raise and race trotters, for instance — as well as "intellectuals, people who are engaged in ideas for a living."