Aesthetic Activist

Jean Dunbar '73 aims to build community — one historically correct house at a time.

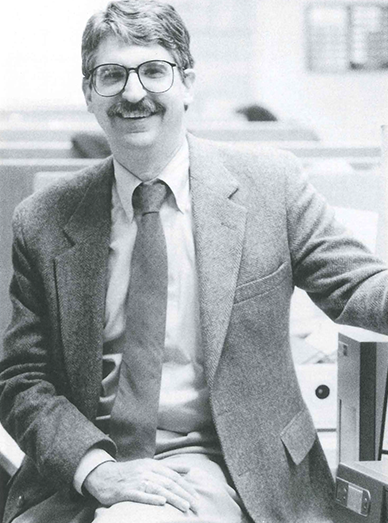

Read The StoryPaul Gherman, director of Olin and Chalmers libraries surveys the present and future of Kenyon's libraries in the digital age.

In his recent work with the Electronic Village Project at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg, Virginia, Paul Gherman caught many glimpses of information technology's future. He saw a digital landscape bright with promise, but also fraught with hurdles. For libraries such as Kenyon's there are parallel sets of hurdles involved in building and refining the physical library while also opening it up to a computer-based future.

In his position as director of libraries at the College, where he has been for more than a year now, Gherman carries responsibilities on both sides of that equation. A key interest lies in keeping Kenyon's libraries in the digital mainstream, even as that mainstream becomes a widening expanse of interlacing rivulets, with information resources intersecting all over the globe.

The fact is, new information services are changing the nature of libraries. Within the stable core concept of hardcopy stacks and periodical indexes is growing a fluid system of digital access and information on demand — a "library within a library," fostered by potential connections with a wide array of information providers. Accommodating both the "physical" and "virtual" libraries is a challenge for which Gherman seems particularly well-suited.

Sitting in his office in Gordon Keith Chalmers Memorial Library, he is obviously pleased with the way the College is keeping up with developments. Gherman believes he's landed in a bright cluster on the Infobahn, seeing Kenyon as a model electronic community where people are adapting with creativity and flair. Whereas the Electronic Village Project was an innovative test-bed-an entire small community connected by an advanced digital infrastructure — the College provides another kind of model: an intensive learning community finding ways to expand its access to the outside world through digital tools. In some ways, it may be a much more realistic paradigm for communities making the best use of new digital capabilities.

Anyone who has taken a recent stroll past the card catalog in Chalmers Library has probably noted the "Card Catalog Closed" signs hanging on the wooden files. There is, perhaps, no better symbol for the present shape of the digital wave. Terminals scattered throughout Chalmers and Olin libraries now offer electronic access to a digital catalog that features impressive search capabilities. The Kenyon College Public Access Catalog is designed to scan vast stores of information, following specific search criteria, and provide up-to-date guidance on the scope and availability of library holdings.

Increasingly, librarians are called on to train new users of this powerful system. They conduct seminars covering the entire range of inquiry possible through the Kenyon library systems, and they regularly guide individual users through their first searches. What users increasingly want is a wider field of research resulting in finer slices of information. Of course, browsing through the stacks can also lead to useful discoveries; but when one compares the experience of wandering through the stacks with that of conducting keyword searches, it quickly becomes apparent which is more immediately productive. Beyond the basics of using both the physical library and the digital interfaces, Gherman sees the future role of librarians as involved in helping people become "wise consumers of information," regardless of its form.

For students of the first generation educated with computers, including all of those now at the College, digital access is a given. They've grow up with it, and they want to refine their on-line research skills by using such resources as the Internet. Increasingly, students want access to electronic indexes for quicker, more powerful, more precise searches. And the emergence of multimedia learning tools (combining audio, video, text, and interactive modeling) is driving learners to demand both access to these resources and guidance in their use. Managing that access and providing that guidance are two of the near-term challenges for Gherman and for librarians everywhere.

"As time goes on," he says, "our tasks as librarians will include teaching people how to access information in the most economical manner possible. Increasingly, people will want to access information directly and, in the process, tailor it to their needs and interests. That model of information consumption is a very different one from the traditional library model of storing, lending, and reshelving books."

We are entering an era of unprecedented access to deep stores of information, Gherman says, with the ability to negotiate vast amounts of data residing in far-flung places to find the most up-to-the-minute data on a world of topics. The advance of digital search and print-on-demand capabilities is changing the nature of the information industry, which is in a period of tremendous uncertainty and flux.

But at the core of that storm is a stable role for libraries. "The principles of librarianship haven't changed all that much," Gherman states. "Helping people determine which information is worthwhile, helping them gain access to it, storing that information for future use, and preserving it" remain the cornerstones of the library function.

One way in which that stable core is expanding is through the use of systems to connect libraries. Presently, students can locate resources available through other colleges and universities and use the interlibrary loan program to request those resources. But Gherman is now working with representatives of a group of area schools to expand that access. With Denison and Ohio Wesleyan universities, Oberlin College, and the College of Wooster, Kenyon is considering how libraries and other campus resources can join forces more effectively.

A joint automated catalog of holdings is under discussion, along with a courier system to move items quickly among the institutions. One hope is that this kind of system could lead to less duplication and thus a richer, more diverse joint collection. Similarly, purchase agreements for electronic databases might be negotiated on behalf of the entire group, thus lowering costs for each participating institution.

All of these prospective plans involve keeping current with the mainstream of technology that exists in the collegiate world. So how does a library keep up with changing technologies?

"We've got one foot in the paper-based world," Gherman notes. "At the same time, we're making the transfer to the electronic world — sometimes buying the same information twice. We're teetering between the two: we can't quite get out of the paper world, and the electronic world is just defining itself. It presents us with day-to-day challenges."

Information providers and publishers are facing the same challenges from the other side: How do they enter this new publishing environment? How do they protect their information resources? How do they price their services, and how do they determine what people want?

Referring back to the Electronic Village Project at Virginia Tech, Gherman describes the concept of creating an "off-ramp on the information highway"-a model environment of an entire community using electronic services. Such developments give rise to significant questions for everyone involved: What kinds of information services will people really use? How will those tools change their lives? How will this change our society?

It was Kenyon's position on the electronic frontier that attracted Gherman in the first place. "The advertisement for the position featured an e-mail address for responses," he remembers. "Right away, that told me something."

Gherman speculates that adding technology links to an already accessible community promises a powerful demonstration of the possibilities for expanded communication and interaction. "I'm intrigued by how faculty members are applying technology to their coursework. For example, [Professor of Anthropology] Rita Kipp has integrated this new communication into her classrooms very dramatically."

Kipp's students are refining their ideas via e-mail after their classes are over, extending their classroom learning beyond the classroom, keeping an "open line" that bridges the gaps between class sessions. As our ability to interact through technology expands, Gherman points out, the process of learning can expand with it.

"We've had a grant from the Pew Foundation for three years," he notes, "helping faculty members integrate new technologies into the classroom as well as redesign courses to take the best advantage of new information resources."

All of these developments are, to Gherman's thinking, very promising. At Kenyon, he says, it's not only the future but also the present that's exciting. As the College moves forward, he sees the day when the kind of after-class connectedness that Kipp's students enjoy might extend to alumni.

The possibility of serving lifelong learners via the information highway is a concept that could work at Kenyon just as it does elsewhere, Gherman observes. "Students leave here with a strong bond to the faculty," he notes. "There may be ways of using technology to maintain those bonds and even expand them."

The thought of building a stronger College community beyond the bounds of Gambier is one that holds bright promise. But, for now, Paul Gherman is focused on the task at hand: accommodating new learners with tools that spiral outward from the stable core of the library, offering opportunities for far-reaching study and satisfaction.

Jerry Kelly '96, who has had a successful career as a technical writer, returned to college this fall to complete his bachelor's degree at Kenyon. He is a member of the Class of 1996.

Jean Dunbar '73 aims to build community — one historically correct house at a time.

Read The StoryFive members of the first class of women reveal a diversity of accomplishments.

Read The StoryHannah More, an early Kenyon benefactor, fought "depravity" with poetry in eighteenth-century England.

Read The StoryAssociate Professor of English Adele S. Davidson '75 reflects on the lost founders of Kenyon in an adaptation of…

Read The Story