The Long-Lost 'Kenyon House'

Peter Dickson '69 explores the history of Mount Vernon's first brick hotel.

Read The Story Life-threatening illness is stressful to both the patient and the patient's family. Someone who knows and understands this on many levels is Katherine N. DuHamel '81, a health psychologist and assistant professor in the program for cancer prevention and control at the Derald H. Ruttenberg Cancer Center of Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. A tireless and wide-ranging researcher, DuHamel has probed the workings of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in bone-marrow transplant, burn, and childhood-cancer patients and their families.

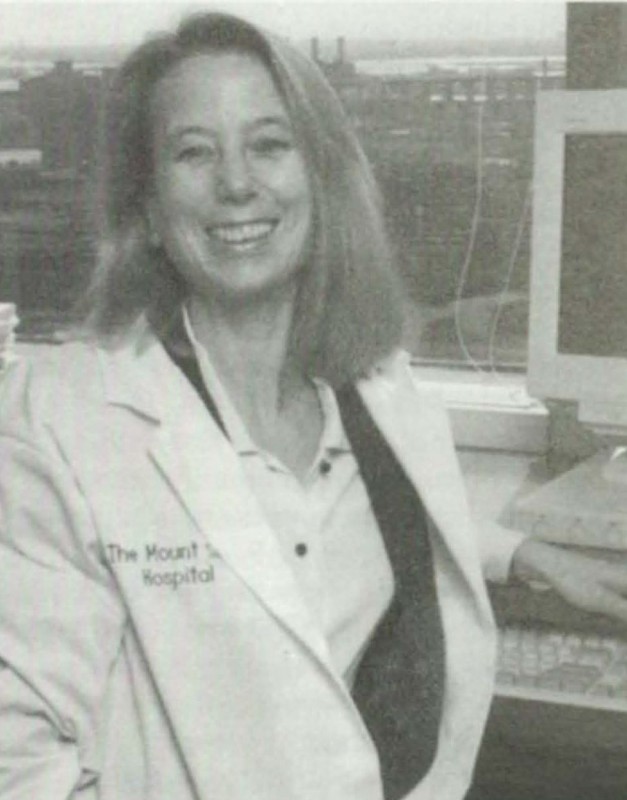

Life-threatening illness is stressful to both the patient and the patient's family. Someone who knows and understands this on many levels is Katherine N. DuHamel '81, a health psychologist and assistant professor in the program for cancer prevention and control at the Derald H. Ruttenberg Cancer Center of Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. A tireless and wide-ranging researcher, DuHamel has probed the workings of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in bone-marrow transplant, burn, and childhood-cancer patients and their families.

DuHamel has been interested in psychology since high school. A native of Montclair, New Jersey, she attended Miss Porter's School in Farmington, Connecticut. When she arrived at Kenyon, she already knew that exploring the workings of the mind would be her major field of study. "In my first year, I was giving a solo dance performance, and I tore the ligaments in my leg," she recalls. "I didn't feel it until I woke up the next morning and couldn't walk. The excitement, dissociation, and 'trance' state of the performance prevented me from feeling the pain, and that really fascinated me."

The fascination has never waned. "I find writing grants and papers for publications and conducting studies is a creative learning process," says DuHamel, who earned her master's degree from the New School for Social Research and her Ph.D. from Yeshiva University. "I'm a very curious person, and I like to apply my knowledge of cancer, research design, clinical interventions, and statistics. The data provides answers to questions that my 'inquiring mind wants to know.'"

DuHamel's inquiring mind has led her down various pathways in addition to her work on PTSD. With her mentor and postdoctoral fellowship advisor William H. Redd (husband of Katherine Khan Redd '78) at Mount Sinai, she has published on the effects of hypnosis, including self-hypnosis, on pain, and on the relationship between hypnotizability and surgical outcomes.

"Kate is a very good business manager, and she also has outstanding skills as a clinician and researcher," says Redd. "This interesting combination of abilities enables her to run very complex research projects with excellent results."

DuHamel, Redd, and their colleagues have published extensively on the treatment of stress symptoms after bone-marrow or stem-cell transplant. "Bone-marrow transplantation is increasingly used in the treatment of hematological malignancies and related disorders," she says. "As the success and availability of the procedure climbs, concern about long-term psychosocial adjustment increases."

PTSD is an anxiety disorder that develops in the wake of exposure to a traumatic event. Defining symptoms include trauma-associated dreams and nightmares, efforts to avoid reminders of the stressful experience, and heightened physiologic arousal. Diagnosis and treatment for life-threatening illness was recently specified for inclusion as a PTSD stressor in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). For the patient who is already trying to cope with the various medical treatments and their side effects, PTSD presents an additional obstacle to overcome, particularly since the triggers of the syndrome are often unavoidable parts of treatment.

"One aspect of my work that I particularly enjoy is helping people cope with a life event," says DuHamel. "First we work to identify their own internal resources and strengths as well as ones in their environment, including social support. I then teach them new skills, such as coping strategies and self-hypnosis. My role is to teach behaviors that help with a specific set of problems arising from being a cancer patient or survivor or having a family member who is. It is quite different from long-term ongoing psychotherapy." The research arm of her work guides her toward those interventions that might be most useful and effective.

DuHamel is anxious to see wider application of cognitive and behavioral therapies to help cancer patients and their families cope with the stressors of potentially fatal disease and its treatment. "I'd like to see a demystification of cancer and its treatment," she says. "Research has shown cognitive-behavioral interventions to be effective in facilitating adjustment to medical illness and treatment, and I believe in those interventions for which there is data from methodologically sound studies on their effectiveness."

DuHamel approaches the design of her studies with the same creativity she brought to the design of dance pieces at Kenyon. "When I danced and did choreography at Kenyon," she says, "I would dream a dance, wake up, and write it down. Now, believe it or not, I dream of studies. Sometimes I dream about the grant for a study, and I'm able to write down the ideas when I wake up."

As a co-investigator with the Katie Couric Colorectal Cancer Initiative at Mount Sinai, DuHamel is researching methods to overcome people's reluctance to undergo the screening procedure for this disease. African Americans, as a group with high mortality, are especially targeted in the studies. "We examine all the stages of approaching a screening procedure and then try to design something to overcome the barriers at each stage," DuHamel explains.

DuHamel comes from a large, close family and enjoys summer get-togethers with them in Little Compton, Rhode Island. "I don't have any children," she says, "but I adore my nieces, Katherine, Grace, and Anna, and nephews, Mac and Gabriel." Around New York, she sees many of her Kenyon friends and takes advantage of the many museums and performing-arts events.

"It's a good life," she says. "I never have a dull moment. Every time I run a new computer program, give a talk, lecture to medical students, interview a study participant, see a patient, or write a grant, I learn something new."

Peter Dickson '69 explores the history of Mount Vernon's first brick hotel.

Read The StorySir Lloyd Tyrell-Kenyon, Lord Kenyon and Sixth Baron of Gredington, delivers the 1999 Founder's Day address.

Read The StoryA look at the Kenyon campus and how it grew.

Read The StoryPresident Robert A. Oden Jr. reflects on Kenyon history in honor of the College's 175th anniversary.

Read The Story