At the Species Boundary

English professor (and dog lover) Jim Carson probes the significance of animals in literature, drawing on insights…

Read The StoryJustin Martin '19 fights for his status quo.

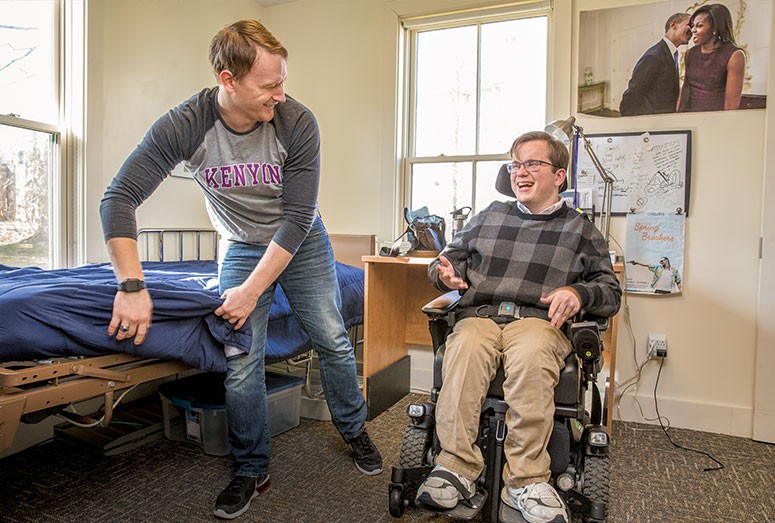

Justin Martin '19, right, laughs with his aide, Alexander Counts.

It was like a scene out of the movie “Groundhog Day.”

In late December, Justin Martin ’19 should have been focused on his upcoming final exams. Instead, he was afraid that at any moment, an obscure legislative rule, which he had fought once already, working its way through state government would force him to withdraw from Kenyon.

Martin learned that the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities (DODD) was trying to pass a new rule that would ban independent home-care providers, who are paid through Medicaid, from working more than 40 hours a week. To Martin, an English major from suburban Columbus, Ohio, who has cerebral palsy, a rule like this would upend his life.

Martin leads a fairly typical college student life. He shares a campus apartment with several close friends (and a friendly kitten), thrives in his classes, helps run an improv group, the Ballpit Whalers, and writes poetry — and comic book scripts — in his spare time. But he couldn’t do any of these things without round-the-clock assistance from four full-time independent home-care providers, who help him with everything from dressing himself to getting in and out of his wheelchair to use the bathroom.

The news hit Martin and his family like a bad case of deja vu. “We were really, really disappointed, obviously, in a way that’s hard to articulate. It’s just kind of a gnawing in your gut,” he said.

Two years earlier, when Martin was a senior in high school, he testified in front of the Ohio House Finance Subcommittee on Health and Human Services, whose members were debating the merits of a proposal to phase out independent providers altogether. If the proposal had passed, Martin, who had received acceptance letters and scholarship offers to various colleges, including Kenyon, would not have been able to enroll at the school of his choice.

"Whether or not I was going to go to college depended entirely on whether or not six or seven people, whom I have never met in my life, think that my life is worth enough to keep putting money into it."

Justin Martin '19

Thanks in large part to his impassioned testimony (and the testimony of others like him who rely on Medicaid), the proposal was nixed — about one week before Martin arrived at Kenyon for orientation.

“What do we tell kids? We say, stay in school, keep your head down and get good grades, so that eventually you can have your pick of where you want to go to college. That just wasn’t my experience,” Martin said. “Whether or not I was going to go to college depended entirely on whether or not six or seven people, whom I have never met in my life, think that my life is worth enough to keep putting money into it.”

This past winter, when Martin heard about the new proposed DODD rule, he knew exactly what he had to do: fight. The rule would create a 14-hour gap in Martin’s schedule during which he would be on his own. And, he explained, finding enough qualified providers so that none works overtime is itself a full-time job — especially in less-populated areas of the state, like Mount Vernon.

While preparing his testimony for the DODD, Martin posted a plea on Facebook, asking friends if they would be willing to speak on his behalf. If the DODD understood exactly what he meant to his college, and what his college meant to him, he reasoned, then maybe they’d rethink this rule, too.

The Kenyon community responded with a groundswell of support, and 21 students, faculty and staff members offered to accompany Martin to the Ohio Statehouse in February. Martin’s friend and housemate Adam Aluzri ’19 immediately jumped into action and, working with Erin Salva, Kenyon’s director of student accessibility and support services, rented three College vans for the trip. Every afternoon before the trip, Martin commandeered a booth at Wiggin Street Coffee and held testimony-writing “office hours” for his friends.

“When you are a disabled person, this idea that you are excessive, or a burden, or too much, it gets accidentally, or sometimes on purpose, drilled into your head,” Martin said. “The idea that people would want to help me and testify for me, not just for a charity case but because they actually value me as a three-dimensional person, is still something I’m learning how to internalize.”

In his own testimony in front of the DODD, Martin proclaimed, “I am not a burden: policies like yours are. Disabilities are not burdens: organizations like yours are. My life is not a burden: apathy like yours is. My people and I will see those burdens transform themselves immediately, or we will throw those burdens, gladly and in public, to the ground.”

The testimony given by Martin’s friends was so powerful that the advocacy agency Disability Rights Ohio published excerpts in an aptly titled booklet, “Medicaid Matters: Justin Martin Rallies His Community to Defend Waiver Services.”

Wes Davies ’17, for example, told the DODD: “The strongest people I’ve met in my life have been the ones who have had to fight the hardest; I look forward to the day when Justin does not have to be strong just to survive, and can get the full provider care he needs.”

Listening to his friends praise him to a panel of strangers was surreal, Martin said with a laugh — kind of like attending his own funeral. But, “to have that outpouring of support at exactly the time that I needed it, meant so much to me,” he said.

Not long after the hearing, Martin was invited back to Columbus to meet privately with the DODD director, John Martin (no relation). Shortly after that, Martin was honored by the advocacy organization Disability Rights Ohio’s “Courage Award” for his activism on Medicaid.

“Justin is an activist at heart because of his immense compassion for others and passion for social justice,” Salva said. “He was able to mobilize a group of students, staff and faculty to be that voice for social justice.”

In April, when the DODD announced that they were pulling the proposal — a victory for Martin and everyone who fought with and for him — Martin breathed a (brief) sigh of relief.

“It’s a great, perpetual and preventable tragedy that so many disabled Ohioans still feel, with good reason, that their rights and dreams could be robbed of them if the political climate changes again,” he said. “If it does, we’ll be there. We’ll be sighing, we’ll be angry — but we’ll be unsurprised and we’ll be there.”

Web extra: Read HuffPost's June 2017 profile of Martin and his fight for access to health care.

English professor (and dog lover) Jim Carson probes the significance of animals in literature, drawing on insights…

Read The StoryA conversation between Laura Hillenbrand '89 H'03 and Julie Barton '95.

Read The StorySix alumni who work with animals share their favorite tips, tales and tricks of the trade.

Read The StoryDrama cats. Presidential dogs. A flock of peacocks. Meet some of Kenyon's most beloved residents.

Read The Story