Aesthetic Activist

Jean Dunbar '73 aims to build community — one historically correct house at a time.

Read The StoryK.D. Novak Burnett '73 recalls the turmoil that led to tranquility.

Were we Women, or were we Girls? In 1968, I was definitely a Girl. Actually, I was a Chick, sweet little sixteen in heavy eye makeup, fishnet stockings and a miniskirt. But although I was showing a lot of leg, the boys got no satisfaction in the back seat. Only grownups had birth control — what a waste!

Song after song had promised that high school would be fun, fun, fun. But the shadow of death had fallen across our beach party. Johnny Angel was going to Vietnam. Pep rallies were canceled by assassinations, riots raged in nearby Chicago. I cried for Kennedy and King and didn't give a damn about the football team. Even a teeny bopper becomes politicized when half her generation is being lined up to be killed.

Dateline Ohio, 1969: I arrived at Kenyon College and fell off the edge of the known world. Freaks were everywhere. The East Coast girls were hip, I really dug the styles they wore. Now I was too embarrassed to wear the to-die-for collegiate wardrobe I had worked for all summer. A sympathetic sophomore gave me a pair of raggedy jeans so I could join the tribe.

Kids who had just come back from Woodstock burbled ecstatically. They had tripped out. They had made it in the mud. They had been Experienced.

But the glow of Woodstock was chilled a few months later by the first draft lottery. I will never forget watching the faces of those young men turned to the television screen, waiting to hear their fate decided by a random number. Someone yelled, "It's time to play ... Beat the Reaper!" Late that night, a shirtless drunk stumbled down Middle Path with a tombstone painted on his chest. In the center was "#1."

It was rough being Draft Bait. If you were epileptic, knock-kneed, schizophrenic, your friends congratulated you on your good luck. But it wasn't easy being Jail Bait, either. With the ready accessibility of the pill, there was suddenly no good excuse for a girl to say no. In fact we weren't Girls anymore, we were Women, with hairy legs, no bras, no makeup and (supposedly) no bourgeois inhibitions. "Do it because you love me" had become "Whatsa matter, Baby, are ya uptight?"

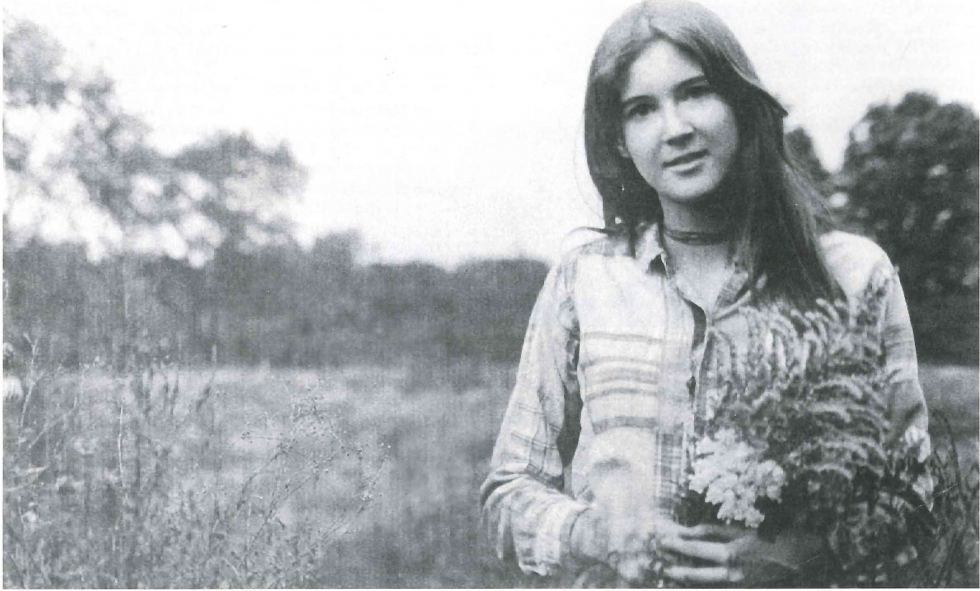

With loss of innocence all around me, I took refuge in the role of the Flower Child: child-like, drug-free, spiritual and monogamous.After running the gauntlet, I settled in with the biggest, sweetest, hairiest guy I could find and hoped that he could protect me form the storm. My girlfriends voted me "Miss Bourgeoisie of 1971" for actually considering marriage.

But there was still the pervasive sexism of hippie culture to contend with. Girls painted signs. Guys were The Steering Committee.

Someone pounding on my door, breathless: Four dead at Kent State! Student strike! This moment was the climax of my freshman year, bringing a time of weeping and fear, courage and high drama. Just up the road, kids like me had been shot for protesting the war. Hell, kids who were just walking to class had been gunned down by agents of Law and Order.

I had to idea that this tragedy would be the high-water mark of the violence my parents' generation committed against my own. Instead, I saw Kent State as the opening battle of The Revolution we had talked so much about. And, at the age of eighteen, I prepared to die. Only a few students from Kenyon braved rumors of massacre and sniper fire to march in Columbus two days later, and I was one of them. It still amazes me that I set off that morning ready to give my life for the movement. (Now, I would probably pray and send a check.)

I quit the Flower Child business and went on to several more incarnations in the hippie pantheon. At twenty, I was a Radical Urban Activist in London. At twenty-two, I was a Free-Loving Communard in Madison, Wisconsin. (There was a brief moment in human history when we had hassle-free birth control, legal abortion and curable venereal diseases. Sorry if you missed it!) At twenty-six, I was a Pothead Songwriter down in Austin, Texas, social workin' by day and slackin' by night.

But in 1979, I found myself gazing into the eyes of a long-haired ex-G.I. who smiled like Elvis, and it was all over. He was unimpressed by my adventures, having had plenty of his own, and we fell into a friendship that endures to this day. In fact, we are married, parents and residents of the suburbs. I guess I earned that "Miss Bourgeoisie" title after all!

K.D. Novak Burnett, who came to Kenyon from Glen Ellyn, Illinois, left the College after her sophomore year and went on to graduate from the University of Wisconsin. (Before departing, she contributed a poem to Hika, the student literary magazine, that the Bulletin editor remembers to this day.) She now works in the health-care field and lives with her family in Beaverton, Oregon.

Jean Dunbar '73 aims to build community — one historically correct house at a time.

Read The StoryAssociate Professor of English Adele S. Davidson '75 reflects on the lost founders of Kenyon in an adaptation of…

Read The StoryFive members of the first class of women reveal a diversity of accomplishments.

Read The StoryHannah More, an early Kenyon benefactor, fought "depravity" with poetry in eighteenth-century England.

Read The Story