The Long-Lost 'Kenyon House'

Peter Dickson '69 explores the history of Mount Vernon's first brick hotel.

Read The StoryPresident Robert A. Oden Jr. reflects on Kenyon history in honor of the College's 175th anniversary.

Story by President Robert A. Oden Jr.

Let me begin with at once an explication of and an apology for my title, beginning with the latter. Many there will be here and in the larger Kenyon community for whom no topic I address will have been forgotten. Many there are whose knowledge of the College's history is deeper than my own, and many there are who will know what truly are the "forgotten moments" in our history. Still, and we arrive now at the explication, I have found that much of interest in Kenyon history is insufficiently widely known. If there are experts on our history, there remain a number of us who know too little and who wish to learn more. It is an awareness of this that lies behind my project, my title, and our observation of the College's 175th anniversary.

A couple of additional disclaimers. First, there is little in our history that is beyond dispute, there is much about which good and wise people have disagreed. Put rather differently, our past has witnessed historical revisions, and this process will and should continue. I have tried throughout to rely chiefly on primary sources, but even here one finds disagreement — so, it will neither surprise nor distress me if you find here commonly repeated errors or legends. Finally, and as will be evident, the demands of limited time mean I've had to make lots of choices, that I've slighted many areas of interest, that the manuscript on which I began last winter grew over the course of the summer to unmanageable size. If my selections frustrate you, then act upon your frustration and discover more.

I will begin by listing for you the "forgotten moments" I aim to recount, trusting my list will aid us in knowing where we've been and where we're going:

If American culture and nomenclature is a happy amalgam of native gifts with those from around the world, nowhere is this clearer than in the names of our grounds, our buildings, our streets, the hills and waters that surround us. Hoping that by mentioning a few of these I will pique your curiosity and perhaps inspire you to investigate others, I want to speak about Kokosing, Marriott, Harcourt, and Cromwell.

Can you imagine Kenyon College without the Kokosing? What if the river bore a different name-as, indeed, it did for a time? We would be without the song "Kokosing Farewell," and hence we could be neither like or unlike Kokosing. More painful still, there would be no Kokosingers, or "Kokes," our beloved male a cappella group.

What do we know about the name "Kokosing"? Like most folk etymologies, distinguishing certainty from legend in our local names is hazardous, and the philologist in me confesses to being skeptically wary of folk etymologies and local legends. But here is what we think we know. We think that the Indians' early name for the stream below the hill was "Kokosing," which perhaps meant "river of little owls." We think that the stream was usually called "Owl Creek" when Kenyon's founder, Bishop Philander Chase, first laid eyes upon it. However, and for reasons that escape us, the bishop preferred to call the stream "Vernon River," and such is the name that appears regularly on the maps of the area that Chase commissioned. What unhappy consequences would have obtained had the bishop's name stuck. We would all sing, on the steps of Rosse Hall and elsewhere, "Vernon Farewell." And the Kokes: surely the Kokes would be known as the "Verns."

Mercifully, several decades after Chase had left Gambier, Bishop Gregory Thurston Bedell (pictured), who had built for himself a grand residence in Gambier that he named Kokosing, pressed for a return to the melodic Indian name for the stream. His pressing worked, Kokosing stuck, and "Vernon River" is now largely and happily forgotten.

Mercifully, several decades after Chase had left Gambier, Bishop Gregory Thurston Bedell (pictured), who had built for himself a grand residence in Gambier that he named Kokosing, pressed for a return to the melodic Indian name for the stream. His pressing worked, Kokosing stuck, and "Vernon River" is now largely and happily forgotten.

There are other names in our history that are now forgotten by some of us that we would do well to remember. What about the proper name for the College park, Marriott Park, the area bounded by the gates to the north and Old Kenyon to the south, and what about the person behind the park's name, George Wharton Marriott?

When Chase was in England, attempting to raise funds for a seminary in America, and when Chase's American foes were attempting to hinder his fundraising efforts, Marriott (pictured) sought out Chase and offered him moral support and more. It was at Marriott's home that Chase was first introduced to Lord Kenyon. It was again Marriott who introduced Chase to another significant British benefactor, the Reverend Dr. Gaskin. Gaskin's help was of such moment to Chase that the latter named a street in Gambier after him. We might think of these personal and topographical relations like this: just as Marriott Park today intervenes, serenely, between Old Kenyon and Gaskin Street, so, too, it was the intervention of Marriott that introduced Chase to both Lord Kenyon and Dr. Gaskin.

When Chase was in England, attempting to raise funds for a seminary in America, and when Chase's American foes were attempting to hinder his fundraising efforts, Marriott (pictured) sought out Chase and offered him moral support and more. It was at Marriott's home that Chase was first introduced to Lord Kenyon. It was again Marriott who introduced Chase to another significant British benefactor, the Reverend Dr. Gaskin. Gaskin's help was of such moment to Chase that the latter named a street in Gambier after him. We might think of these personal and topographical relations like this: just as Marriott Park today intervenes, serenely, between Old Kenyon and Gaskin Street, so, too, it was the intervention of Marriott that introduced Chase to both Lord Kenyon and Dr. Gaskin.

However, and demonstrating again that not all of Chase's preferences were perfect, it was not Chase who designed Marriott Park as we know it today. In fact, he wanted to allow traffic to drive right up to Old Kenyon. He planned for the street to open out widely in front of that glorious building into a spacious area to be called Bexley Square. How fortunate we are that Chase's plans in this instance were not fulfilled.

If we owe the name of Marriott Park to George Marriott, we owe the design to another, David Bates Douglass (pictured), whose name I hope all of you will pause to read on the College gates. When Douglass became Kenyon's president in 1841, he viewed the College's grounds with fresh eyes and discerned no reason why wagons and carriages needed to drive straight to Old Kenyon. It was Douglass's plan rather to stop traffic at Wiggin Street and to force such traffic to go around the College park to the west and the east. We are the forever-grateful beneficiaries of this plan.

If we owe the name of Marriott Park to George Marriott, we owe the design to another, David Bates Douglass (pictured), whose name I hope all of you will pause to read on the College gates. When Douglass became Kenyon's president in 1841, he viewed the College's grounds with fresh eyes and discerned no reason why wagons and carriages needed to drive straight to Old Kenyon. It was Douglass's plan rather to stop traffic at Wiggin Street and to force such traffic to go around the College park to the west and the east. We are the forever-grateful beneficiaries of this plan.

Indeed, the spaciousness of Kenyon is one of the chief shapers of our campus's beauty. A helpful analogy here is the difference between Cambridge and Oxford universities. Because I was a Cambridge undergraduate, and because Cambridge is characterized above all by spaciousness, I think of Kenyon as a rather Cambridge-like place. Great as are the buildings of Oxford, and as a group they probably are more impressive than Cambridge's structures, an Oxford graduate would be deeply puzzled were we to tell her or him that Kenyon had a space problem. "Space problem?" our Oxford woman or man would say. "You have no space problem; I could build you three or four colleges between Peirce and Rosse halls." A Cambridge graduate, on the other hand, would under-stand: Kenyon does have a space problem precisely because spaciousness is among the keys to our architectural and landscaping vocabulary.

To another name, Harcourt. The College gates' inscriptions speak also of Middle Path as a place of song. When David Bates Douglass was Kenyon's president, there was little tradition of singing, either here or at any American college. German institutions did possess such a tradition, and it was our students traveling abroad who imported this tradition to the College.

One song little heard today is that which contains the lines, "So here's to the health of Old Kenyon/And the Harcourt girls so dear." "Harcourt girls" in these lines is not a reference to the women and girls whose families were members of Harcourt Parish and who filled the pews of the Church of the Holy Spirit along with Kenyon faculty members and students on Sundays. The name "Harcourt" was first uttered in Gambier about 1827, when the Episcopal Parish was founded, named after the Reverend Sir Harcourt Lees of Ireland. Bishop Charles Pettit McIlvaine (pictured), who succeeded Philander Chase both as bishop of Ohio and as president of the College, later built a home for himself and called it "Harcourt Place." It stood roughly between where Norton and Watson halls now stand. Some years later, Bishop McIlvaine moved to Cincinnati, and his former home became the Harcourt Place School of Boys.

One song little heard today is that which contains the lines, "So here's to the health of Old Kenyon/And the Harcourt girls so dear." "Harcourt girls" in these lines is not a reference to the women and girls whose families were members of Harcourt Parish and who filled the pews of the Church of the Holy Spirit along with Kenyon faculty members and students on Sundays. The name "Harcourt" was first uttered in Gambier about 1827, when the Episcopal Parish was founded, named after the Reverend Sir Harcourt Lees of Ireland. Bishop Charles Pettit McIlvaine (pictured), who succeeded Philander Chase both as bishop of Ohio and as president of the College, later built a home for himself and called it "Harcourt Place." It stood roughly between where Norton and Watson halls now stand. Some years later, Bishop McIlvaine moved to Cincinnati, and his former home became the Harcourt Place School of Boys.

That institution closed in the 1880s, and there then flourished in Gambier for about five decades a boarding school for girls, a school called the Harcourt Place Seminary for Young Ladies and Girls. The course of study for Harcourt Place Seminary was planned with the advice of Alice E. Free-man, the president of Wellesley College, and all of the initial faculty members had links with Wellesley. So highly regarded was the seminary and its curriculum that for years graduates of Harcourt Place Seminary were admitted, without any further application or examination, to Smith, Vassar, Wellesley, and Wells colleges. There is even a sense in which Harcourt Place Seminary can be called the location of Gambier's first college education for women, this because the seminary's faculty was supplemented by no fewer than four Kenyon professors and because the seminary did offer a two-year post-high-school course.

The school closed, a victim of the Great Depression, in 1936, and its demise was suitably marked by an article in the Collegian. "Those of us who knew Harcourt," the articles reads, "will probably miss it. . . . Gambier is now given over to masculinity."

Still, Harcourt was a good idea, a very good idea, an idea eventually reborn in the 1960s, in a Kenyon moment that will and should never be forgotten, that of opening the College to women, first through the establishment of the Coordinate College for Women and then, shortly afterwards, with the admission of women directly to Kenyon. If I utter silent prayers with some frequency for much that has transpired in the College's history, for no single change in our past am I more grateful than the admission of women to Kenyon. The change made us a far, far finer college.

Finally, in my greatly abbreviated list of some local names, I come to Cromwell. Given that the College was founded as an Episcopal institution, surely, we can rightly guess, surely Cromwell stems not from Oliver Cromwell. It does not. The name comes rather from William Nelson Cromwell (pictured), a great benefactor of Kenyon who, like a number of the College's most generous friends, did not graduate from Kenyon. Cromwell was a highly successful New York City attorney, who early in his career became a partner in the still vibrant firm of Sullivan and Cromwell. Beginning about the turn of the century, Cromwell's attention turned significantly toward philanthropy and travel. What happened to many of us when first we drove up the hill happened to him. He hopped out of his car hard by the College gates, looked about, and announced that this is what a college should be. He became a friend to both the College and to President William Foster Peirce, and over the first decades of the twentieth century gave to Kenyon the funds to build first Cromwell House and then Peirce Hall.

Finally, in my greatly abbreviated list of some local names, I come to Cromwell. Given that the College was founded as an Episcopal institution, surely, we can rightly guess, surely Cromwell stems not from Oliver Cromwell. It does not. The name comes rather from William Nelson Cromwell (pictured), a great benefactor of Kenyon who, like a number of the College's most generous friends, did not graduate from Kenyon. Cromwell was a highly successful New York City attorney, who early in his career became a partner in the still vibrant firm of Sullivan and Cromwell. Beginning about the turn of the century, Cromwell's attention turned significantly toward philanthropy and travel. What happened to many of us when first we drove up the hill happened to him. He hopped out of his car hard by the College gates, looked about, and announced that this is what a college should be. He became a friend to both the College and to President William Foster Peirce, and over the first decades of the twentieth century gave to Kenyon the funds to build first Cromwell House and then Peirce Hall.

Another personal note: it is Cromwell House, not Cromwell Cottage. The latter name arose both as some peoples' notion of Cromwell's architecture and as something of a joke. But look, please, at the engraving above the door: House, not Cottage.

There are other names and places of great interest. Let me tantalize you with a few in closing this section. First, you should know that the names Nu Pi Kappa and Philomathesian were originally those of literary societies, groups that began as secret societies but later became more public. Secondly, the historically accurate name for the tower at the front of Peirce Hall is Chase Tower, not Peirce Tower. Like most Gothic architecture, Peirce Hall was intended to be landscaped with nothing but grass right to the wall and the door. Vegetation, especially the now-large trees, ought not be there, though the environmentalist in me shrinks from the thought of taking them down.

Many will know that the domestic Gothic home positioned today next to the Kenyon Inn and in which the dean of students and his family live is properly named Clifford Place, though we often call it Neff Cottage or Neff House. The Neff in question is one Peter Neff (pictured), a successful inventor and businessman, who lived in the house in question from 1860 until 1888, and one of whose daughters was named Clifford, hence Clifford Place. Pause, please, some-time in front of Ascension Hall and note the engraved stone at the base of a tree near Middle Path, and you will read "Peter Neff, 1849," the year of his graduation from Kenyon.

Many will know that the domestic Gothic home positioned today next to the Kenyon Inn and in which the dean of students and his family live is properly named Clifford Place, though we often call it Neff Cottage or Neff House. The Neff in question is one Peter Neff (pictured), a successful inventor and businessman, who lived in the house in question from 1860 until 1888, and one of whose daughters was named Clifford, hence Clifford Place. Pause, please, some-time in front of Ascension Hall and note the engraved stone at the base of a tree near Middle Path, and you will read "Peter Neff, 1849," the year of his graduation from Kenyon.

If, to many of us, even to those of us who live within a few hundred feet of the Church of the Holy Spirit, the sounds that accompany the passing of each quarter hour and the music produced by these bells on other occasions are lovely and constant reassurances that we are, indeed, in Gambier, the sounds were otherwise greeted by Neff. At a length typical of written disputations from this era, Neff produced in May of 1880 a nineteen-page open letter indicating his own displeasure with the "Gambier Chimes." Since few, and certainly not I, could outdo the clarion crotchetiness of Neff's account, allow me, please, to cite numerous passages from this open letter.

Neff begins by noting that "the long cherished desire of Bishop Bedell for a chime of bells was gratified" when sums were raised in the late 1870s to purchase the required machinery, thus, in Neff's words, "carrying out Bishop Bedell's high English notions for everything appertaining to Kenyon College." He first takes on the nine bells themselves, 6,161 pounds of bells located but forty feet up from ground level. "This location," Neff writes, "of itself is sufficient to make all these bells a disturbing element, and a nuisance, quite contrary to the Christian principles generally governing the `sects' in avoiding the erection of bells on their churches, as a general thing, on account of their annoyance to the neighborhood." He then takes on the clock, which strikes the hours on one of the largest of the bells, and the "Cambridge Chime" which strikes on four of the smaller bells the quarter hours. "They strike," writes Neff, "in slow and measured time, and produce harsh, inharmonious peals. There are forty of these strokes every hour throughout the entire day, and the entire night, in addition to the hour strokes, making 960 strokes of the `Cambridge Chime' and 156 strokes of the clock-Pause! Think of it! From 11 to 12 o'clock at high noon and midnight, we have 79 strokes to tell us it is passing from 11 to 12 o'clock-being a total of 1,116 separate and distinct strokes every day," yielding "vibrations and sound waves, which roll and reverberate through the house."

Perhaps composing his letter to the very sounds of these bellicose bells, Neff begins to get his second wind. "Were these forty quarter-hour strokes of any absolute utility, or did they serve any necessary beneficial purpose, or were they any part of the march of civilization, there might be some excuse for them; as it is, there can be no reasonable apology for the constant unwarranted clatter. . . . This `Cambridge Chime' is a cruel, inhuman torture to be under all day and all night; they are horrid in the still-ness of the night. . . . They have impaired our health, and are shortening life."

If bad for all, then worse still are the bells for those living nearby. "How cruelly the bells are inflicting pain and disease on those residing close by the bells, and who cannot get away from under their pernicious influence. . . . Place yourself and family in my location, about seven hundred feet distant. . . . How would you like this ding dong every fifteen minutes? . . . [It is] machinery wearing out flesh and blood to those who have any nerves. It is too much bell-ringing . . . it is a sickening nuisance."

Certainly, Neff continues, "no country in Europe would tolerate such bells," bells which "it was left for the Dark Ages to develop." Why, then, should "so quiet and retired a retreat as Gambier" have to endure "so peculiarly and harassingly noisey a set of bells?" Threatening legal action, Neff notes that the sounds of "a pig pen" or "the braying of an ass" would surely be "abated by law," so why not the "pernicious influences" of the bells?

Instead, however, of abating the noise, Kenyon officials, writes Neff, have resorted to "personal abuse of myself and family" and "to systematic bulldozing all who raise a voice against the bells." Thoughts of this give rise to Neff's peroration. "These bells cause a blight in their vicinity; they drive people off the street . . . and depreciate the value of property. . . . They are bad enough in the day time, producing discomfort and injury to health, interrupting conversations, interfering with business. . . . But at night, when all is still and quiet about the house, and the atmosphere moist, then it is that the pernicious effect produced is beyond description, and beggars language to depict their diabolism. . . . Oh horrors! We retire in dread, we moan in sleep, as they artificially arouse overtaxed nature . . . and hour after hour is passed in vain efforts to get used to the thumps."

In fact, of course, most villagers liked the chimes. And over the years the College's efforts to placate Neff damaged the bells. Neff, as perhaps the above rants indicate, had lost credibility. He was, in short, a crank, a crank who eventually solved what was for him almost alone a problem by moving away, at long last out of earshot of the dreadful bells.

We have seen, in our visits here and there to Kenyon history, that the College saw the birth of many fine ideas, and were there sufficient time, we'd see more fine ideas. College songs were a good idea. The Harcourt Seminary and eventually Kenyon as a college for both women and men were very good ideas. There are other good ideas like this, ideas now so commonplace that we take them for granted.

One such idea is that of granting college credit to incoming students who had taken special advanced-placement courses in high school. If today a half a million students in fourteen thousand schools world-wide participate in the official Advanced Placement (AP) Program, none of this was true as recently as the 1940s and all of this is true today because of Kenyon's leadership. Indeed, the College can accurately be called the birthplace of the AP Program, a program often called in the early days "The Kenyon Plan."

In a few minutes, I will speak at greater length about the role played by President Gordon Keith Chalmers in leading Kenyon to its present prominence. It was again he who led the College and others to consider granting advanced placement credit to incoming students, though he was assisted by Professor of Chemistry Bayes M. Norton and others. An important stage in the development of the AP Program was "The School and College Study of Admission with Advanced Standing," and a doctoral dissertation submitted to Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1967 says, of this study, that "President Gordon K. Chalmers of Kenyon played the key role. He initiated preliminary meetings that led to a proposal for the experiment; he become the first chairman of the Central Committee of the [School and College] study;" and he served on the inaugural AP board until his untimely death in 1956 (Donald Bruce Elwell, "A History of the Advanced Placement Program of the College Entrance Examination Board to 1965," 1967). As early as 1947, Chalmers had argued publicly for the academic upgrading of America's schools and colleges. In particular, he felt that too little in-depth study of academic disciplines, especially foreign languages, obtained in American education.

These ideas Chalmers developed in the final years of the 1940s until he presented them more formally to a meeting of the Private School Association of the Central States on March 31, 1951, in Chicago. That same year, Chalmers issued invitations to the presidents or their representatives of eleven colleges to further the plan of offering advanced placement to high-school graduates who had demonstrated their competency in various subject areas by successfully passing "genuine college-level courses." The eleven colleges and universities represented at the meeting in New York were Bowdoin, Brown, Carleton, Haverford, Kenyon, Middlebury, MIT, Swarthmore, Wabash, Wesleyan, and Williams; several months later, Oberlin joined the group.

Acting in accord with the recommendations of a Kenyon committee chaired by Norton, the College's faculty formally voted to participate in the nascent AP Program in November of 1953. That spring, a three-day conference was held, on this hill, to discuss implementing the program. There are, naturally, many further details, including the assumption by the College Entrance Examination Board of the administration of the plan. But what matters is the idea, what matters is what was begun here at Kenyon. If there are any regrets about the AP Program, my sole regret is this: that the early name, "The Kenyon Plan," is not that by which we today entitle the program.

Finally, I wish to address a fourth topic in my account of some forgotten moments in the College's history, that I label, with some understatement, "Some tragedies of the 1950s." Between early 1954 and the spring of 1958, Kenyon learned of the deaths of several prominent professors, administrators, students, and the College's president, Gordon Keith Chalmers. Mortality, you might be tempted to respond, is mortality; we are the animals, perhaps uniquely the animals, who are aware of our own mortality, so what's remarkable about Kenyon and the 1950s? What is remarkable is the number of those who died unexpectedly-and often while still at the height of their powers. What is remarkable is the small size of the Kenyon community in this era. And what is remarkable is the leadership roles played by those who died in so short a period.

During the 1950s, the College climbed as high as we ever have climbed in national rankings. As a nation, we are, it has often been observed, uniquely intrigued by, some would even say obsessed with, rankings: the best one hundred novels of the twentieth century, the finest ten movies ever, the dozen best places to eat in Manhattan, and so forth. In the 1950s, it was the annual Chicago Tribune survey of American colleges and universities to which much importance was attached, and Kenyon was ranked third in the nation among private men's colleges.

Much of the credit for our stature then, whether measured by national rankings or by other criteria, goes to Chalmers and to the faculty members he recruited to the College. Chalmers became Kenyon's president in 1938 at the age of thirty-three. He selected and appointed every new faculty member in accord with his own demanding criteria for scholarly accomplishment and teaching ability. Chalmers's own writing, the flourishing of the Kenyon Review, and the teaching and research of the faculty all drew worldwide attention.

Chalmers was also fortunate; international economic and political circumstances aided him in elevating the College. Thus, in the 1930s and 1940s even some of the finest young scholars in the world were desperate for academic positions. Distinguished scholars were fleeing Europe, eager for teaching and research positions. Salaries in the Depression years and beyond were low everywhere, thus making it possible to recruit to Kenyon a superb faculty at a cost even the financially stressed College could bear.

Chalmers's own writing and his friendships with academics across the globe granted to him access to the finest faculty talent. At least as importantly, he was an intensely learned and serious scholar who impressed those he wished to attract to Kenyon, and he was a superb judge of which candidates for positions at the College would make the best faculty members. His own self-confidence and his focus upon Kenyon's central mission led him to make many faculty appointments with little or no consultation-with faculty members or with anyone. In a college that had an enrollment of four hundred and a faculty of about forty, by about 1955, there were, as there are today, nationally recognized scholars in every department.

It might well and persuasively be argued that few individual human beings have ever placed their personal stamp on any college or university as Chalmers did at Kenyon. If his authoritarian style caused deep resentment in the faculty, and it did, equally significantly, there was nothing like a deep administrative team to continue his mission if he could not. Nor was the faculty likely to accept a successor of Chalmers's habits. Chalmers was thus, in a sense, the College's greatest strength and its greatest vulnerability: what would happen in his absence?

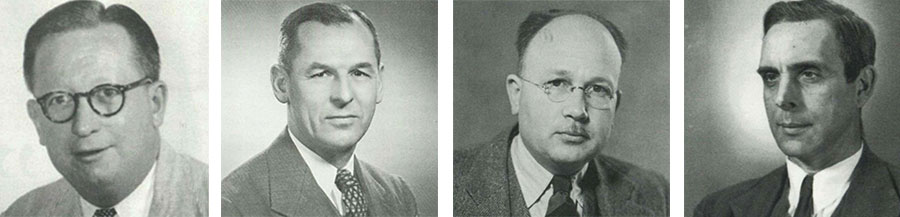

Directly to the point of this forgotten moment in Kenyon history, a series of tragedies in the mid-1950s might have destroyed the College. Even an incomplete account of some of these tragedies tests our sympathies. In January of 1956, Philip Blair Rice (pictured below, left), professor of philosophy and one who played a key role in the leadership of the Kenyon Review, died in an auto accident. In May of that same year, two students died in a plane crash near campus. Later that same month, President Chalmers (pictured below, second from left) died of a stroke. Two months later, in July of 1956, Charles Monroe Coffin (pictured below, second from right), chair of the English department, died of a heart attack. Rice, Chalmers, and Coffin were each fifty-two years old. In April of 1957, two students died, again in an auto accident, near the middle of the campus. A month later, Philip Wolcott Timberlake (pictured below, right), chair of the English department, died of a stroke. In May of 1958, Edgar "Ted" Bogardus, Yale younger poet of the year in 1953 and managing editor of the Kenyon Review, died at the age of thirty of carbon-monoxide poisoning along with a student, Daniel Ray, who was captain of the swimming team. And in July of 1959, Edson R. Rand, chief financial officer of the College, died of a heart attack at age fifty-seven in his Kenyon office.

If the cumulative effect of these tragedies dealt the College a near-fatal morale blow, the loss of Chalmers was particularly painful. When Chalmers died, Kenyon lost not only its leadership but also the person most able to raise funds to build the kind of endowment needed to sustain a college of the first rank. The College drifted toward bankruptcy, and many wondered if Kenyon could sustain itself as the first-rate college it was and is.

The visionary financial leadership and resolute courage of many allowed the College not only to survive but to flourish on the far side of these tragedies. Any list of those most responsible for the skill and boldness with which Kenyon faced these trials would be incomplete, but certainly the list includes many faculty members, Vice President for Finance Samuel S. Lord, Provost Bruce Haywood, Dean Thomas J. Edwards — perhaps Tom Edwards as much as anyone. Eventually, the College took a step as important as any in our history, that of including women in the Kenyon student body, that of increasing the enrollment at the College and thereby allowing it to begin once again to attain financial stability. New and talented faculty members were recruited; new and talented students, both women and men, were drawn to the revived institution. Kenyon not only survived; the College flourished and continues so to flourish as we seek again to claim our place among the United States' finest colleges.

At once sadly and triumphantly, the story above is anything but atypical. As McIlvaine Professor of English Perry C. Lentz '64 has brilliantly argued in the Bulletin, Kenyon's is a history of tragedies — fires and financial woes and more — that would have brought a college with lesser resolve, with a less keen sense of its mission, to its knees. As we celebrate the College's one hundred seventy-fifth anniversary, may we never lose this resolve and never stray from our mission, that of offering as fine a liberal-arts education as can be obtained anywhere.

Editor's note: President Oden delivered a version of this article as a Common Hour presentation on Oct. 5, 1999, in honor of the College's 175th anniversary.

Peter Dickson '69 explores the history of Mount Vernon's first brick hotel.

Read The StorySir Lloyd Tyrell-Kenyon, Lord Kenyon and Sixth Baron of Gredington, delivers the 1999 Founder's Day address.

Read The StoryA look at the Kenyon campus and how it grew.

Read The Story