A Life Uncommon

Henry Abraham '48 has survived — and studied — key historical moments that changed the world. At 97, he reflects…

Read The StoryTen alumni who work in local, state and national politics share how they got their start, the lessons they've learned along the way, and how they're working to make a difference in their communities — and for their country.

Story by Erin Peterson | Art by Carlos Chavarria, Jodi Miller, Agata Nowicka and Kate Warren

There’s no question that the rough-and-tumble politics of the past few years have had plenty of us attached to our screens. But the attention-grabbing headlines on the national scene have often obscured the powerful political work that is happening at other levels.

Perhaps you spotted Lizzie Pannill Fletcher ’97 in the grid of women’s faces lining the cover of the Jan. 29, 2018, issue of Time magazine, or followed as Fletcher, a Democrat, successfully ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in Texas’ 7th Congressional District in November, defeating nine-term Republican incumbent John Culberson. Or maybe you were glued to the news on June 12, 2018, watching the historic North Korea – United States summit take place in Singapore and taking pride in the fact that then-White House deputy chief of staff Joseph Hagin ’78 was a key player behind the scenes and helped make it happen.

Dozens of Kenyon alumni are rolling up their sleeves and getting to work as city council members, mayors and leaders of political organizations, as well. They are making real change, and their ambitions will likely take many of them much further. We asked 10 alumni, who are working in local, state and national politics, to share how they got their start, the lessons they’ve learned along the way, and how they’re working to make a difference in their communities — and for their country.

Lucy Vinis ’74 is mayor of Eugene, Oregon.

Lucy Vinis ’74 had always been deeply involved in her community — mostly environmental work with local nonprofits — but it wasn’t until 2015 that it occurred to her to spin her desire to improve her community into a run for elected office.

At a potluck, a friend who was in the legislature told her she should run for mayor of Eugene. She wasn’t sure she’d take the suggestion seriously, but not long after that conversation, her 23-year-old son told her the same thing. She still marvels at that moment: “Within two days, I had young people and more seasoned people saying, ‘You should do this.’”

She did.

Vinis ran for mayor and won the race decisively. Though she didn’t have the typical resume of a mayor — she hadn’t served on the city council, for example — her work in nonprofits prepared her well. She could write, speak, fundraise and find possible solutions to complicated issues.

Nonetheless, her first few months as mayor sometimes felt disorienting. “Since I had worked in nonprofit [fundraising], I had spent my whole life calling up people who didn’t exactly want to hear from me,” she jokes. “The great pleasure of my role now is that everybody wants to hear from me. When I walk into the room, people see it as a benefit, because the mayor showed up.”

Vinis said she’s proudest of sanctuary laws she’s championed and helped pass, which ensure that city resources are not used to enforce immigration laws. “It’s a statement about protecting the rights of individuals in our community,” she said.

For Vinis, her work as mayor simply expands the impact she has always tried to make through her work. “It wasn’t that I thought ‘I could work in government,’” she said. “It was that I thought: I have always acted on my values, and now I have an opportunity to act on these values in ways that might be able to change the default — the way we’ve always done things.”

Nick Gasbarro ’15 works as a special assistant to Ohio Senator Rob Portman.

When I first started as an entry-level staffer for Senator Portman in 2015, I was answering phone calls and talking to constituents who held a wide range of political views. I didn’t know people really called their senator!

I was surprised by people’s anger from both sides of the aisle. It really makes you think about whether we can reconcile our views and unite as a country. You read about the state of politics in our country, but living it and feeling the emotion is eye-opening.

Now, I spend my time helping prepare the senator for meetings, speeches, hearings, phone calls and events in Washington, D.C. I monitor his interactions in the Capitol and manage personal correspondence coming from the senator.

It’s inspiring to work with people who genuinely care about the future of our state and country. It may not always look like it to those on the outside, but a great deal goes into shaping policy and legislation with the purpose of doing the right thing. It’s an honor to step into the Capitol every day for work, and an even greater honor to help represent family and friends.

Jonathan Rothschild ’77 is mayor of Tucson.

I was an attorney in private practice for 28 years, and during that time, I got involved in the community — part of nonprofit organizations, my synagogue, a senior center. And when I would read the newspaper, I’d sometimes get the impression that our city government was not operating as it should. I figured, heck, I could do better than that.

I helped out in local elections. I helped (former U.S. Representative) Gabby Giffords throughout her elections. I learned a lot, and in 2011, I decided to run for mayor. It wasn’t exactly that simple, but I secured the Democratic nomination without opposition and won the general election. I’ve been mayor ever since.

The mayor ahead of me — a very nice guy — had gotten the reputation as a ribbon cutter. Just a ceremonial guy. I made a vow that I would never cut a ribbon.

In my first week as mayor, I was asked to cut a ribbon, and I went out and did it.

There went that vow.

What I learned was that when you go to those events, you find out what’s going on in your community. You talk to people. You take the pulse of the community. And as a leader of a community, you’re important to people. You’re out there, and you’re encouraging them to do more good.

When people trust their municipal government, they will invest in it. In other words, trust makes them more open to increasing their taxes or [supporting] a bond. Since I’ve been mayor, we’ve passed three significant initiatives: two bond issues, for roads and parks, and a temporary sales tax for roads and public safety. It makes me proud that we’ve been able to operate a city government in a way that makes people trust us and trust their community.

The best political job in the world is being a mayor of a city in the United States. You’re local. You don’t have to be ideological. You have real problems in front of you, and you try to figure out a way to solve them.

Michara Cramer '20 spent the summer as an intern for EMILY's List, a political action committee that helps elect female Democratic candidates who support abortion rights.

When Michara Cramer '20 talks about her reaction to the 2016 election, she doesn't mince words. “I was devastated,” she said.

She also knew she was anything but helpless. She took stock of her options and became laser focused on women's rights.

As an intern form EMILY's List this past summer, her job made the most of the research skills she's been honing at Kenyon. Among er duties were to do public record deep dives on both EMILY's List candidates and their opponents. She fact-checked claims in political ads and other communications. She monitored candidates' campaign media.

She saw that she could play a role in something that felt like a much bigger movement. “Seeing many of the EMILY's List candidates win their primaries throughout the summer was extremely rewarding,” she said. “Knowing that so many people support our endorsed candidates and want to see change — it's made me feel very hopeful.”

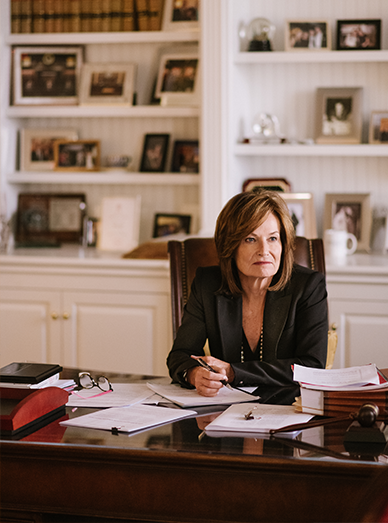

The Hon. Kathleen O’Malley ’79 H’95 was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit by President Barack Obama in 2010.

The selection and confirmation process for federal judges is surprisingly politically charged. That said, it has been my experience that most judges work hard to put all that behind them when they take the bench. I can recount many cases in which I would have ruled differently if free to make the law rather than follow it, or over which I lost sleep because of what my oath of office required of me.

Becoming a judge is jarring because of how isolating it is. When you come from a world where your friends are often lawyers, it is difficult when you can neither socialize with them nor allow them to do even the smallest favors for you. Even accepting a cup of coffee from someone appearing before you is impermissible. I feel like I lost some sense of community and narrowed my world of close friendships. Now I know many more people from all over the world, but on a less personal level.

One of the most moving things I’ve done is preside over the swearing-in ceremonies of new citizens. It is [astonishing] to realize how much more they know and appreciate about our Constitution and system of government than many naturally born citizens of this country do. I am greatly moved by their love of this country.

If you want to be a judge, you can read books that inspire you to care about the law, like “Gideon’s Trumpet,” or biographies of famous jurists. Practical tips? Take a logic course. Analyzing and interpreting the law is largely based on logic.

Zack Space ’83 was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 2007 to 2011, and most recently ran for state auditor in Ohio.

I got involved in politics in my 40s based on a personal issue: My congressman at the time decided not to override a presidential veto linked to embryonic stem cell research. I knew my son, who has Type 1 diabetes, could have benefited from that research.

So I ran for his position and I won. It helped that he ended up going to prison — not for his veto, obviously! But the timing was good for me.

My district, which includes many poor and rural counties, lacked access to technology, including broadband access. I did what I could to fix that, which included bringing more than $100 million to southern Ohio to build up a broadband network. I believe that has significantly improved the lives of a lot of rural Appalachian Ohioans. It’s enhanced education and health care. That feels satisfying.

Even though one issue motivated me initially, I also knew that politics, when practiced properly, was an amazing venue to get things done. Through politics, you can effect policy that has a meaningful impact on people’s lives. You can try to rectify what you see as wrong.

Sarah Longwell ’02, chair of the Log Cabin Republicans, shares four ways to make a meaningful political impact.

Think outside the tent. There are big ideological tents that divide people into the Republican camp and the Democratic camp. When I was younger, I thought that once you chose a side, you had to embrace every stance and talking point of that side. As I got older and more confident in my own ideas, I realized that there were ways to work in politics on individual passions that don’t conform to party orthodoxy.

Work to shape your own party’s policies. It’s okay to be a dissenting voice within your party and to change it from the inside. Gay marriage wasn’t really an issue [for conservatives] when I was getting involved in 2005. I’m gay, I’m conservative, and I wanted to get married. It always struck me that it was more effective to be a voice within your own party advocating for something to friends and allies than to be an outside voice yelling in.

Use language that resonates. The left makes arguments in ways designed to appeal to their audiences. The same principle works on the right. It helps to use language about family, and to focus on the idea that people want to participate in marriage because they think marriage is a good institution. That made a difference. Conservatives could talk to other conservatives in their own language about the importance of marriage equality or about the importance of repealing Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

Stay optimistic and practical. In this moment, it’s easy to look at politics and say, “No thanks. That is a toxic environment.” Don’t think that way. There is always good, worthwhile work to be done. People hear too much of the national back-and-forth, and that’s not where good work happens. It gets done in policy shops in D.C. and across the country. There’s a big world out there, and a lot of good people on both sides of the political aisle work hard for what they believe. It’s possible to hold on to your principles, work in politics, and change things for the better.

Sarah-Marie Choong ’17 was a field organizer for J.B. Pritzker’s gubernatorial run in Illinois. She currently works for a federal contractor in Arlington, Virginia.

Sarah-Marie Choong ’17 had a post-college plan before she ever stepped on Kenyon’s campus, so she certainly didn’t expect to be transformed by a 100-level class. “I arrived at Kenyon interested in pursuing law, but instead found a place in the political science major after taking “Quest for Justice” with [Assistant Professor of Political Science] Lisa Leibowitz,” said Choong. “That introductory course showed me the importance of articulating and debating the basic questions embedded within current political conflicts and controversies.”

Choong has gone on to work on numerous campaigns. As a field organizer for Illinois gubernatorial candidate J.B. Pritzker, she spent her time meeting with current and potential volunteers, attending local political groups’ meetings, hosting campaign phone banks, and organizing meet-and-greets for the candidate.

If you like novelty, she said, field organizing is a great gig. “Organizers do not tend to have regular schedules,” she said. “Every day looks different depending on what the campaign needs or when volunteers are able to come and help with events.”

It’s a path she’d encourage for anyone interested in politics: “Good organizers with campaign experience are in high demand,” she said. “It’s worth it to get involved.”

Caroline Nesbitt ’73 was a Democratic candidate for the New Hampshire House of Representatives in 2018.

Aside from a Civil Rights march in Detroit at age 13 and a march on Washington, D.C., after Kent State with a huge Kenyon contingent, I had pretty much avoided active politics.

But then I saw my son, Alex Butcher-Nesbitt, get fired up about politics. He wasn’t in the streets. He was helping elect people. It was a revelation to see how hard he worked inside the system that I had thumbed my nose at years ago. He was trying to get good people into office instead of trying to throw people out.

After our current president was elected, I started “threatening” to run for office. The tipping point came when a friend emailed me a link to an EMILY’s List “Run to Win” training. It was like throwing down the gauntlet. Was I serious, or was I just talking?

I went to the training and was completely overwhelmed. I went to bed that night thinking, “There’s no f***ing way I can do this.” But when I woke up, I was working on my elevator speech.

After the shock wore off around the community I’ve lived in since 1973, I received an outpouring of support that totally blew my mind. Friends just started handing me money. Some of my first supporters were women from Kenyon’s first class of women in 1973, which was humbling and lovely.

Still, I was a dark horse. On primary day, four of us in three locations stood all day long in the pouring rain, holding up my little sign and chatting with all comers. My goal was just to get on the ballot for the general election. Against all odds and expectations, I won the primary by a large margin.

I didn’t win the general election in my ruby red district. But I came close, and gained a much deeper sense of the importance of being a part of the solution rather than part of the problem, to paraphrase activist Eldridge Cleaver. So I’ll be back.

Courtenay Corrigan ’88 is former mayor and current city council member for Los Altos Hills, California.

Courtenay Corrigan ’88 had spent years volunteering on various committees in Los Altos Hills, a small town just south of San Francisco. So when a spot on the city council opened up, it seemed like her logical next step.

For Corrigan, the joy of working on a city council comes in part from the fact that decisions she helps make lead to changes people can literally see — from public art displays to ordinances that affect the placement of sidewalks. That said, the breadth of issues she and others cover is so wide that it feels daunting. Residents expect council members to become instant experts on pet projects — and even the most popular issues can get unexpectedly sticky.

For example, when a resident suggested installing automatic license plate readers to combat a rise in crime, the idea seemed like a slam dunk. A slew of residents had already advocated for the readers.

But then she arrived at the city council meeting. “Because of the [privacy issues] the topic triggered [interest from the] local chapter of the ACLU,” she said. “We usually have 20 people in attendance, but that night, we filled chambers and had a two-hour discussion on the invasion of privacy. We ultimately voted not to do it.”

Corrigan said that such flashpoints illustrate that there’s rarely an easy answer to any problem, and that good public servants need to be willing to do plenty of due diligence to find a good answer. “You have to do your homework, talk to the residents, understand how your neighbors feel, and form your opinion,” she said. “The minute you start really peeling the onion, you realize there’s a lot of complexity in even issues that seem simple.”

From Nick Gasbarro '15: Leverage the Kenyon network. I scoured LinkedIn and worked with the Kenyon Career Development Office to track down Kenyon alumni in D.C. One alum had worked on Capitol Hill for years and taught me how everything worked — the things you don’t necessarily learn in political science class. (This kind of networking can help you) understand how soft skills and a liberal arts background are transferable to Capitol Hill.

From Zack Space ’83: We develop reputations in our communities based on our actions and our relationships. The best thing that a young person can do to lay the groundwork for a future political career is to start now. Be someone who’s hard-working, who’s compassionate and who’s willing to give back to their community. I know that sounds corny. But it’s overlooked.

From Courtenay Corrigan ’88: Town committees are a great entry into politics. Most towns have five to 10 of them at least: public art, education and open space, for example. So many decisions are being made in these committees by volunteers.

Henry Abraham '48 has survived — and studied — key historical moments that changed the world. At 97, he reflects…

Read The StoryThe College is campaigning to make wellness, and sleep, cool on campus. Will it work?

Read The StoryA photo essay by Erin Schaff '11, who has been recognized as one of the top photojournalists working in Washington…

Read The Story