Peace in Earth

Kenyon’s land trust turns a golf course into a public nature preserve—including space for environmentally friendly…

Read The StoryA reigning force on the young-adult best-seller list, Ransom Riggs '01 pulls in readers with haunting imagery and explores the shadows between fantasy and reality.

Story by Megan Monaghan

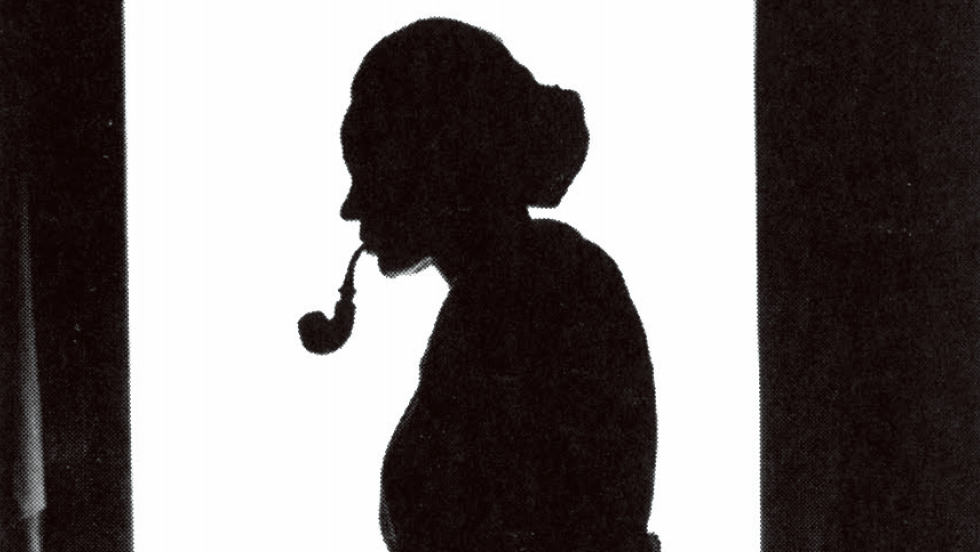

Ransom Riggs ’01 always felt he was “a little bit peculiar.” But then again, he added, “I didn’t feel any stranger than most of my friends.” The best-selling author of Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, the surprise young-adult hit lauded for its strange mix of fantasy and eerie vintage photography, grew up writing stories and making movies with those friends in the backyard of his Florida home. The time he spent at the Pine View School for the Gifted, which Riggs jokingly called a “school for nerds,” shielded him from the teenage rites of sports teams and lunch rooms. “It was a safe place to be a nerd and love books,” he said.

His love for books drew the aspiring writer to Kenyon, where he majored in English. “You come up onto this Hill and, suddenly, you’re in this other universe where it’s 1824 and all of the buildings look like that era. It feels like a secret little world,” said Riggs, who since has built his career on the allure of secret worlds, exploring them through fiction.

His second book, Hollow City, which was published earlier this year, was praised by the Boston Globe as a “stunning achievement” and “even richer than Riggs’s imaginative debut.” The hotly anticipated Miss Peregrine’s movie, to be produced by Twentieth Century Fox and directed by Tim Burton, is set for release next summer.

“There is an authentic danger and magic in his books,” said P.F. Kluge ’64, Kenyon’s writer-in-residence who taught Riggs in a fiction writing course. “He keeps the pages turning.”

When Riggs returned to Kenyon this spring for a campus talk and book signing, he sat down with the Bulletin to discuss his accidental path to the best-seller list and what he has in store for Miss Peregrine and her band of peculiar children.

Your first book, Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, debuted on the best-seller list. What was that experience like for you?

John [Green ’00] called me after my book hit the best-seller list and said he was ready to have this conversation with me about how you don’t hit it out of the park on your first at-bat and that it’s okay, because a lot of good books don’t get noticed. It took some conversations like that for me to realize how unusual it is to have your first book debut on the best-seller list. We were able to sell the movie rights before the book came out, so that created a little bit of buzz. It’s probably the reason we got a write-up in Entertainment Weekly.

Were you surprised at the book’s instant success?

I was convinced it was so wacky that it would just be a novelty gift item and disappear quickly. I also figured it would hit the best-seller list for one week and that it would be a nice moment I’d always remember before going back to my normal life. But it stayed. It stayed and stayed and stayed, and it’s still on it.

Did you intend to write a young-adult book?

I was writing a young-adult novel; I just didn’t know it. I hadn’t read a whole lot of young-adult books before I wrote it, but when I started to look around the young-adult section of the bookstore, I was delighted and flattered. I’m really glad to be writing young-adult books for these fans who are so passionate and so vocal. And so smart. The young-adult genre feels like a special, warm, fuzzy place in the writing world.

How did it end up being a young-adult book if you didn’t conceive it that way?

Barnes & Noble shelved it in the young-adult section.

That’s it?

Yeah. I guess there were some internal conversations at Quirk Books, my publisher, that it seemed to fit the young-adult genre. But Barnes & Noble has a lot of power, and if Barnes & Noble refuses to stock your book, that can kill your book. They also can go back to your publisher and say that you should change the cover. That happens very frequently. So when Barnes & Noble said, “This is young-adult,” we said, “Okay.”

You didn’t have to make any changes to your book after it was labeled young-adult?

I didn’t even have to take out the f-word. Which I should have, in retrospect.

How has Miss Peregrine’s changed your career?

I thought I was headed down a path of being a screenwriter, and then I started this arduous slog to get noticed and pulled out of the slush pile in Hollywood. And Miss Peregrine’s took me out of that. And I’m so glad that I am writing books now. I always wanted to make movies but, honestly, screenplays are not my favorite thing. A screenplay is not a finished product. Someone else takes it and changes it, so it becomes just a blueprint. A book is a final product. When you’re finished, the product is finished.

After graduating from Kenyon, you earned your master’s in fine arts in film from the University of Southern California. How did your time in film school influence your writing?

It forced me to be a visual storyteller. I already had that instinct, but it really drills into you to tell stories without an overabundance of dialogue and to tell stories economically and quickly. There’s a real emphasis placed on action per page when you’re writing a screenplay. It was very freeing to turn to novels and write as much as I wanted, but I couldn’t shake the “don’t bore them” instinct.

What can you do with novels that you can’t do with films?

In novels, there are still actors performing the scenes, but they are actors you generate in your own head. It’s much more participatory for the reader. Readers have to imagine what you’re writing, and make the story come to life in their own minds, and they become a part of that experience. Everyone has a different experience with reading a book. A film is more of a fixed thing where everyone experiences it the same way.

How involved have you been in the movie adaptation of Miss Peregrine’s?

It’s pretty rare for movie studios to involve the writer of the book, because book writers are notoriously curmudgeonly and have lots of strong opinions. But the studio has shown me a couple drafts of the script and sought out my opinion. Sometimes they call me with story questions and ask me to explain things like time travel. Luckily, I wrote a story that’s so complicated that they need my help. Otherwise, I don’t think they would ask for it.

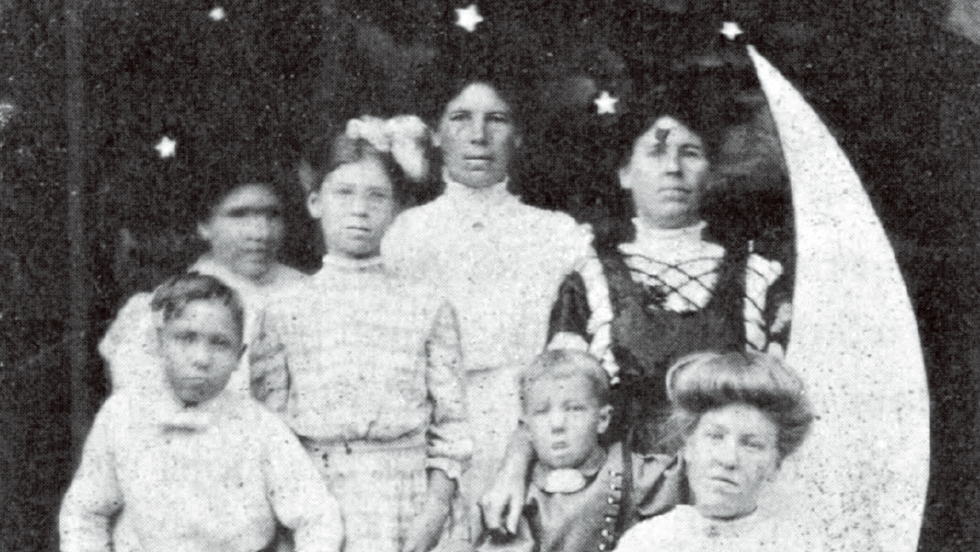

How did you start collecting the vintage photos that are featured in your books?

I started collecting them at swap meets and, as my collection started to grow, I didn’t really know what I was getting into. I wasn’t buying them for any specific purpose, until it started to grow in my mind that these strange old Victorian images could be something, a book of some kind. I didn’t even really know it was a novel until I talked to my editor, and he suggested it.

How did the photos inspire the story?

I used them like a casting director uses headshots of actors when he’s casting a movie. I would find a photo to fit the character, or sometimes the photo would dictate the character’s peculiarity. When I found a photo of a kid covered in bees, I created a character who could control bees with his mind.

Miss Peregrine’s was your first novel. How did you start the novel-writing process?

My publisher gave me four months to write the first book. I just ran to my keyboard and started typing, which was great, because I didn’t have time to overthink it. So, I wrote a book in four months, and it was not very good. When my publisher gave me four more months, I threw away the book I had written and wrote a different one, which is essentially the book that Miss Peregrine’s is today.

You ended the first book on a cliff-hanger before getting a deal for the second book. Did you know what you would write about next?

I had some vague ideas. But when I started to write the second book, I threw them all away and began something else. The world is so open I could have gone anywhere. And I did make the characters go everywhere before I figured out the right path. I wrote probably eight-hundred pages to get to the three-hundred or so pages that are in the final novel. I went down a lot of blind alleys.

Do you have an ending foreseen for the third and final book in the series?

I do know what’s going to happen in the third book. I actually thought I could finish the series in the second book, but it’s like an oasis. You think you’re there, and then it recedes in the distance, and it’s farther away than you thought. I probably could have made the second book a hundred pages longer and rushed it to an ending, but I wanted the story to have room to breathe and be mature and come to life. Every time I think it’s done, it’s not. The book tells me I’m wrong.

Kenyon’s land trust turns a golf course into a public nature preserve—including space for environmentally friendly…

Read The StoryLike many college yearbooks, Kenyon’s "Reveille" has fallen on hard times in recent years. Observers blame uneven…

Read The Story