Tuning into Childhood

Musician, tunesmith, and pied piper, Justin Roberts ’92 enchants children and hooks their parents.

Read The StorySabbaticals for a semester or a year keep Kenyon’s tenured faculty energized, engaged, and immersed in their fields. But critics claim that the breaks may do little more than take professors out of classrooms on subsidized vacations.

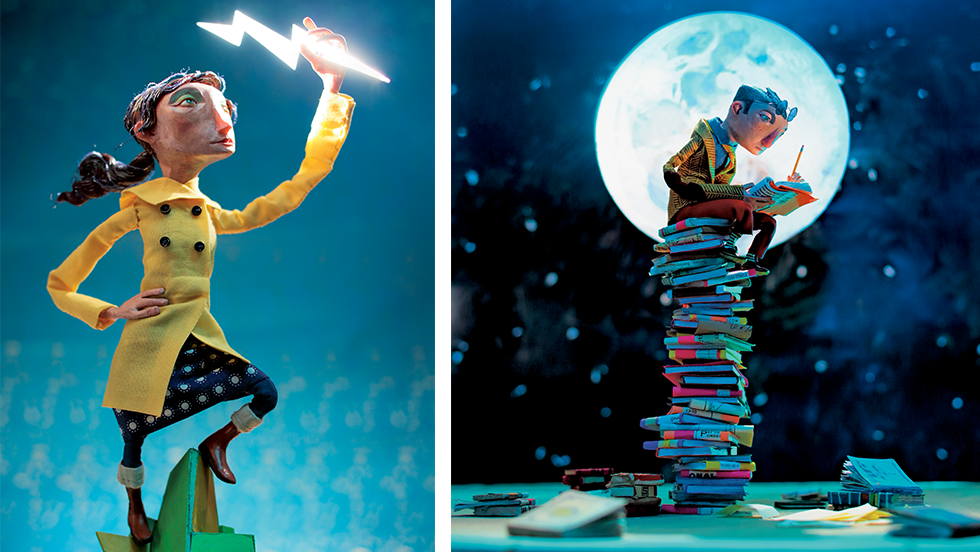

Story by Joel Hoekstra, illustrations by Red Nose Studio

Lunch with the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board usually requires an appointment and the kind of résumé that impresses American presidents.

But last fall, Will Melick, Bruce L. Gensemer Professor of Economics, spotted Ben Bernanke striding toward his table in the employee cafeteria at Fed headquarters in Washington, D.C. The nation’s chief monetary architect set down his tray and began chatting with Melick and his colleagues.

“Before I came to Kenyon, I spent eleven years working at the Fed,” Melick said. “I can tell you that Alan Greenspan never ate in the staff dining room.”

Melick returned to work at the Fed this year while on sabbatical leave from Kenyon. “If you want to understand what’s going on in the field of monetary economics and policy, it’s hard to imagine a better place to be,” he said. Superstar economists visit the Fed every week, offering seminars and giving talks. Melick has access to data and information that would be difficult to obtain in Gambier. And, he said, his year away from Kenyon will enrich his teaching when he returns to the classroom next fall.

Like most American colleges and universities, Kenyon offers its tenured faculty the opportunity to take paid sabbatical leave every seven years. Each semester, about twenty-five faculty members are untethered from their teaching obligations and given a chance to do research, write books, visit other institutions, create art, compose music, or pursue other academic interests. The break in routine is more than just a breather. “Sabbaticals are used to create knowledge,” said Jan Kmetko, associate professor of physics. “You need time for that.”

But sabbaticals aren’t offered by every college and university. And as the price of higher education has climbed, some critics have questioned the cost and value of such leaves. In 2008, the University of Iowa slashed in half the number of sabbaticals it offered, and lawmakers in Wisconsin have threatened to do away with them altogether. Truman State University abolished sabbaticals in 2011 due to budget constraints. And when Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal axed sabbaticals from state budgets three years ago, he said the cuts would “force professors to actually spend more time in the classrooms teaching and interacting with students.”

Kenyon professors can opt for a one-semester leave at full salary or a full year of leave at five-sixths of their pay. To qualify, professors put together a proposal, which the provost must approve. “In general, what I’m looking for is how they expect to grow,” Interim Provost Joe Klesner said. Proposals are rarely rejected. When professors return, they must write a brief report on how they spent their time outside the classroom. In addition, some professors share things they learned on sabbatical by giving a lecture, presenting a concert, or mounting a show. “It’s a way of giving back to the community,” Klesner said.

Most schools in Kenyon’s peer group also grant sabbaticals to tenured faculty, though the terms may vary. Bates College offers full pay to professors for semester-long sabbaticals—and half salaries for full-year leaves. Carleton College relieves professors from teaching duty for a trimester, but full-year leaves are rare and not compensated beyond the first trimester.

To critics and many outside academia, of course, the word sabbatical sounds remarkably like vacation. “At most schools, the professors are living for the sabbatical, when they can get away,” said Claudia Dreifus, coauthor with her husband, Andrew Hacker, of Higher Education? How Colleges Are Wasting Our Money and Failing Our Kids—and What We Can Do About It. An instructor at Columbia University, Dreifus is critical of her fellow academics and decries spending on amenities, describing, in the book, the Kenyon Athletic Center as the “Taj Mahal of an athletics center.” “Sometimes you get valuable work from sabbaticals, but, anecdotally, I can tell you that most sabbaticals seem more personal than research-based,” she said.

Dreifus also questions the purpose of sabbaticals at Kenyon and other schools that are focused on teaching. In the early 1980s, she said, small schools began to emphasize research in the same way that larger institutions like Harvard, Princeton, and state universities did. Liberal arts colleges began to imitate research institutions. “There was a shift in education from being student-centered to being focused on books and prestige,” Dreifus said.

The books and research produced on sabbaticals are often mediocre, she contended. “The production of such works—some useful, but most unnecessary—should be lower on the list of priorities,” she said. “I think paying people not to teach is a very bad idea. I think it devalues the idea of teaching.”

What’s more, the costs of sabbaticals are considerable. In addition to paying the salaries of professors on leave, schools often pay for temporary instructors to fill in. And Dreifus wonders how sabbaticals benefit students: “Suppose you’re a parent saving up so your kid can attend this expensive school and study with this well-known professor,” she said. “Odds are good that he or she will be on a sabbatical leave when the student arrives or has time to take his or her class.”

Are sabbaticals nothing more than paid playtime? “That’s an absurd misconception,” said Kmetko, who last year spent a yearlong sabbatical working at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. “I think I worked more hours, including night shifts, and many weekends in the lab during my sabbatical than I normally would.” Professor of Art Claudia Esslinger, who is currently on sabbatical developing an art installation, dismissed the idea that such leaves are exploited for loafing. “Faculty are the most motivated people I know,” she said. Usually, she added, they have too much they want to accomplish in the time allotted—even when it’s a full year.

The use of sabbaticals by Kenyon professors varies widely. Associate Professor of Chemistry John Hofferberth remained on campus during his sabbatical last year, completing several research projects and queing up new ones that are now run by students. “It’s an amazing opportunity to get some research done,” Hofferberth said. “As an empirical scientist, I need to go into the lab, and that—plus the analysis and writing—takes a lot of time.”

Many professors spend a portion of their sabbatical traveling or living abroad. Jerusalem, London, and New York City are among the locations visited at length by professors on leave. Esslinger, who has taken four sabbaticals during her thirty years at Kenyon, has used her time outside the classroom to fly to Nicaragua, participate in artist residency programs in Germany and Northern California, and, recently, to visit Ireland, England, Spain, and Italy, where she attended the Venice Biennale. “It’s really important for me as a faculty member and artist to know what’s going on in the art world,” she said. “Normally, I’d be teaching or preparing for class and wouldn’t have time to go.”

For some faculty, sabbatical travel sheds light on new avenues for research. Professor of Art History Sarah Blick has specialized in English medieval art for years, but only on a recent visit to the United Kingdom did she realize that many country churches housed enormous and ornate baptismal fonts with curious covers—an art form that hadn’t been researched or written about for nearly a century. That became a new research focus, and she will lead a National Endowment for the Humanities summer workshop on the topic.

Leaving the campus for a short duration can also mean the chance to work at the Federal Reserve, operate a million-dollar piece of equipment at the Oak Ridge Research Laboratory, or—in the case of Professor of Mathematics Judy Holdener—learn an entirely new field of mathematics while teaching at a larger institution. “I felt like I needed to throw myself into the fire,” Holdener said, explaining why she moved to Pittsburgh for a year to teach at Carnegie Mellon University, tackling courses that would require her to stay one step ahead of her students. “I deliberately chose to teach courses that would stretch me in some ways.”

The contacts provided by such off-campus experiences can be invaluable. And in an age where cross-disciplinary work is considered essential to the birth of new ideas, it’s important that professors have the time to make connections with experts in and outside their fields. “Here at the Fed,” Melick said, “almost all of the 200 people in my division are working topics that overlap with mine. You can’t spit without hitting someone else who is interested in those issues.”

To offset the cost of sabbaticals, Kenyon administrators have tried to minimize the expense in larger departments by adding one more faculty position to the tenure-track line. “Essentially, we’ve decided to ask those departments to expand by a position and then not replace the first sabbatical in any given year,” Klesner said. “This saves us search costs and assures we have quality instructors.” Kenyon now replaces only about ten faculty per year due to sabbaticals.

Not all faculty opt to take sabbaticals. And many have to consider carefully the cost versus benefits of taking a full year’s leave at reduced pay. “Many faculty members and their families find living on the reduced salary, which a full year’s leave entails, a sacrifice they cannot make,” Klesner said.

For faculty who travel or relocate on sabbatical, the impact on family relationships can be considerable. Holdener removed her two young children from their neighborhood school and brought them along to Pittsburgh during her stint at Carnegie Mellon, but her husband, Eric Holdener, assistant professor of physics and scientific computing, remained behind in Ohio. He often visited the family on weekends, but the drive and the distance took a toll.

Complications aside, most faculty members say they return to the classroom refreshed, reinvigorated, and better prepared after a sabbatical. The real beneficiaries of sabbaticals are Kenyon students who receive instruction from better teachers, professors said.

If you’re going to do good teaching, you have to have an intellectual background and that comes through scholarship and research."

Jan Kmetko, associate professor of physics

Blick has found that sabbaticals help her develop courses in areas where she isn’t a specialist and broaden her knowledge of the entire field of art history. Kmetko returned to campus more eager to interact with students, noting, “If you’re going to do good teaching, you have to have an intellectual background and that comes through scholarship and research. Without that, I don’t see how you can push students.” Associate Professor of German Paul Gebhardt, who spent part of last year on sabbatical learning Spanish in Mexico City, said his experience reminded him what it’s like to be a student. “Going through an immersion course gave me more empathy for German language learners,” Gebhardt said. And Klesner emphasized that research is important at colleges that place a high value on teaching “because of the way in which it keeps teacher-scholars engaged in their disciplines and alive as thinkers.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the value of a sabbatical may be the only topic on which 100 percent of Kenyon faculty essentially agree. “If you really want to know the truth,” Esslinger said, “I think everyone should get a sabbatical.”

Joel Hoekstra is a freelance writer who lives in Minneapolis.

Musician, tunesmith, and pied piper, Justin Roberts ’92 enchants children and hooks their parents.

Read The StoryPhilander’s Phebruary Phling brought the heat to thaw the winter blues and, for over two decades, took its place…

Read The Story