Peace in Earth

Kenyon’s land trust turns a golf course into a public nature preserve—including space for environmentally friendly…

Read The StoryLike many college yearbooks, Kenyon’s "Reveille" has fallen on hard times in recent years. Observers blame uneven funding, lack of interest among students, and social media.

Story by Joel Hoekstra with photos by Max Aldrich

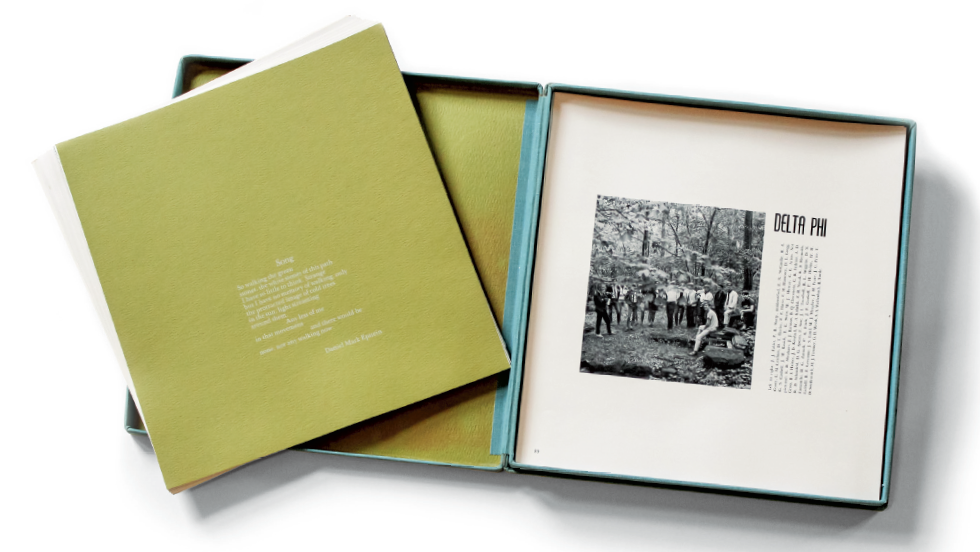

The "year box" they called it. Dusty blue and embossed with a large stylized 1968, the 11-by-10.5-inch cardboard case resembled nothing so much as a deluxe record album. It contained more than one hundred unbound pages filled with black-and-white pictures of life at Kenyon during the height of the Vietnam War, as well as a poster pullout of the administration on the steps of Rosse Hall, posed like a rock band. But was the 1968 edition of Reveille actually a yearbook? The question befuddled librarians and delighted students.

“Now, when I think about it, it was really a dumb idea,” said Greg Spaid ’69, who edited the volume and now teaches art at Kenyon. “The pages don’t stay together. You don’t know if you have a full volume or not.”

Shortcomings aside, the year box significantly impacted the life of at least one Kenyon student: Spaid’s work on the annual publication sparked a passion for photography within him. Graduating with a fine-arts degree, he enrolled in a graduate program specializing in photography and returned to campus to teach the subject in 1979. “It probably isn’t too big a stretch to think that my experience working on Reveille altered the path of my career,” Spaid said.

Such Reveille-related tales, though, may soon become a thing of the past. Yearbooks are an institution in decline: sales of high school and college yearbooks across the United States have dropped roughly 5 percent annually in recent years, according to figures reported on CNNMoney.com, and many schools—ranging from sizable Purdue University to smaller liberal-arts colleges like DePauw and Carleton—have ceased publication altogether.

Budget cuts can be blamed in some instances, but mostly a lack of student interest has precipitated their demise. The Economist called the trend early, in 2008: “With social networks linking hundreds of friends and offering digital photographs and videos, the traditional yearbook looks like a bit of a dinosaur.”

Kenyon’s new Reveille is scheduled for publication and release in early fall. But its size is slim, and its future remains uncertain. Can the annual survive in the modern age? Should it?

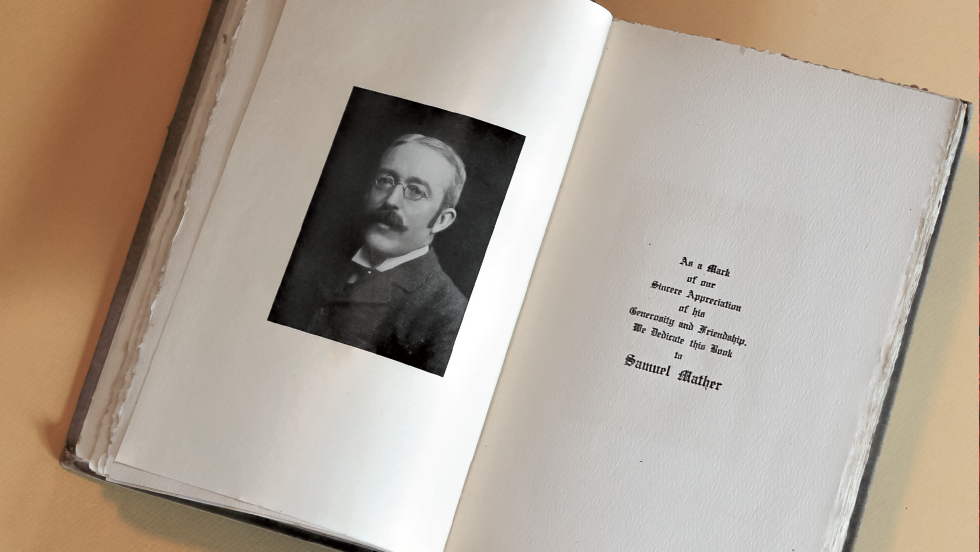

The first Reveille was a single folio—just four 18-by-10-inch sheets when folded—published in 1855. Its maker was the undergraduate D.D. Benedict, who, according to legend, carved the illustrations (primarily fraternity symbols) with a pocketknife into rough-cut applewood planks he had polished smooth on the tombstones of Kenyon’s cemetery. Intended as a portrait of Kenyon life, it followed in the tradition of annuals established at Yale and Amherst, listing the faculty, the students, and membership in the school’s six fraternities and three literary societies, as well as its choir, orchestra, and cadets. A tribute to the editor-publisher in the 1901 Reveille noted that Benedict himself “oversaw the entire work of printing the paper and never for a moment considered his work done” until the first issue appeared in late 1855. Subsequent editions appeared twice a year.

“Like a lot of early yearbooks, it didn’t bear much resemblance to the kind of yearbooks we think of today,” said Kenyon historian Tom Stamp ’73. It lacked pictures of students, professors, and campus landmarks. The writing was sophomoric and satirical. Each issue contained a long editorial laced with platitudes and overblown rhetoric addressed at freshmen and prospectives. (“Kenyon College leads the van of Western Institutions.... Let each and all cherish our glorious Alma Mater.”) It cost five cents and contained ads for the Riley House, a “public accommodation,” and Mrs. Sawyer’s Hot Coffee and Oyster Saloon.

The origins of the publication’s name remain unclear. Though spelled like the word for a bugle call used to wake military troops, the title has for decades been properly pronounced “ruh-VAYL-yuh” among Kenyonites. Stamp says the name is likely related to a poster that appeared on campus about the same time, bearing the headline “Revile Ye.” (Adding to the confusion, a sendup of Reveille, labeled “The Revile-Ye,” was published sporadically in the 1860s.)

Whatever its origins, the name Reveille certainly conjured martial images in the minds of the editors that followed Benedict. “Once more our bugle sounds its notes of greeting,” reads a typical introduction. As Kenyon society grew to encompass clubs devoted to chess, wicket, baseball, boating, and football, plus a glee club and a string band, Reveille trumpeted the success to anyone who cared to know. Its editors chronicled the rise of literary societies with collections of books and periodicals that often dwarfed the holdings of the College’s own library. Early editions of Reveille catalogued the average size and weight of graduating seniors as well as preferences in facial hair (1870: “Imberbes 5; moustaches only 2, siders 2; imperial 1; chinners only 2”) and future professions (1880: physician, grain dealer, journalist, preacher, surgeon, minister, politician). Editorials referenced the arrival of railroads in Gambier and pledged to support/oppose women’s suffrage.

Pages were added as Reveille editors sought to convey the energy and expansion of campus life. A dozen years after its establishment, the publication had shed its folio form and, in the words of its staff, “a tasty pamphlet” had taken its place. By 1877, the publication was a whopping eighty-eight pages. A few years into the new century, Reveille became a full-fledged hardcover book.

As a business enterprise, however, the publication struggled almost from the start. Advertising from local businesses provided a small source of revenue. (Three years after its debut, Mrs. Sawyer remained a stalwart Reveille sponsor: “Madam Sawyer—Still continues to cheer the hearts of lovelorn and despondent students with excellent Oysters, Turkey and magnificent Coffee.”) And national advertising—from livery makers, glove manufacturers, and, increasingly, a raft of cigarette companies—brought in some cash.

Income from alumni subscribers and others, which kept many annuals afloat at other institutions, proved unpredictable and often laughably meager. Kenyon’s alumni weren’t numerous enough to support such a publication. So the fate of Reveille depended on the junior class, which had adopted a tradition of gifting the publication to the senior class. In cases of financial shortfall, publication often lapsed for a period until students revived it. “After silence of two years,” the editors of the 1886 edition proclaimed, “the Reveille again sounds its little note.” A decade later, the staff celebrated the “awakening of the Annual from its sleep of several years”—whereupon it immediately fell into slumber again for another six years.

Only in 1910 was the funding problem fixed: A fee would be assessed to all students, the editors announced, “so that it is a burden to no one.”

“There was a time at Kenyon when being editor of Reveille was a prestige position,” recalled Stamp. For decades, several rooms in the upper floors of Peirce Hall were reserved for leaders of student government and editors of campus publications. Students who held the posts received free board. “I think I gained 10 pounds that year,” joked Spaid, because he didn’t have to walk to dinner.

As members of this elite tribe, Reveille’s editors sometimes saw themselves as keepers of Kenyon’s traditions—and sometimes as revisionists and revolutionaries. Reinvention was part of the recipe almost from the start: “We have left the old beaten track and present to you an ‘experiment,’” the editors announced in the introduction to the 1867 Reveille. Evolution was expected. The first photo plates—depicting the Gates of College Park, Rosse Hall, and a select number of clubs and teams—appeared in 1894; two decades later there was a picture of every senior.

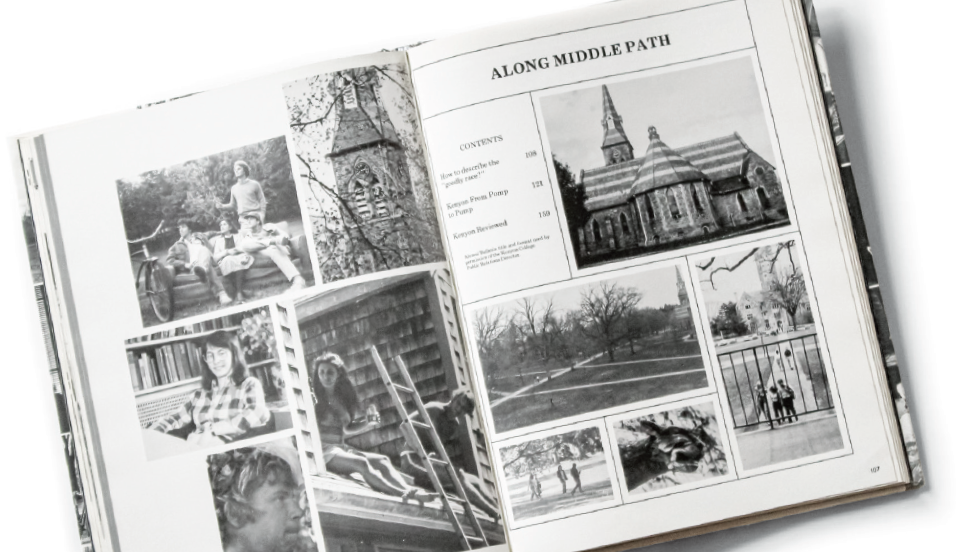

But few editors were content to publish the volume without leaving a personal thumbprint. In the pages of Reveille, they eulogized deceased professors and bemoaned mandatory attendance at chapel services. During World War I, and again during World War II, dedications were made to fallen soldiers. And then, in the 1960s, editors began to turn the entire yearbook notion on its head: text was replaced with photos; formal senior portraits were abandoned in favor of candid snapshots; the yearbook became a year box.

Myer Berlow ’72, Reveille’s editor in 1971, jumped at the chance to edit the publication. He was persuaded, he said, by a classmate who exclaimed, “You get $10,000, all the free film you want, and you can make a statement that will last for a very long time.” Berlow and his staff created a three-volume yearbook that fit neatly inside an elegant gold slipcase. Seniors were depicted in candid shots, but they weren’t listed in alphabetical order. Text was minimal. Mood was everything. It was, indeed, a statement.

But did such yearbooks accurately reflect life on campus—the original mission of the publication? No, according to then-Kenyon archivist Thomas Greenslade ’31. “After looking at this ‘yearbook’ I suggest that a thorough examination and a complete evaluation of the purposes of this publication are in order,” he wrote to President William Caples in 1969. “The Reveilles of the past two or three years have been absolutely useless for archival purposes. There is poor identification of pictures, no records are included, student and faculty coverage is inadequate and incomplete.” The 1969 edition, Greenslade lamented, even failed to mention Caples’ own recent inauguration.

Complaints about Reveille were not uncommon. A letter published in the Collegian in 1985 bemoaned the yearbook’s lack of polish, numerous typos, and “sloppy” production values. “The wasted potential is worse than the errors themselves,” the alumni authors chided.

The biggest challenges faced by Reveille editors in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, however, had nothing to do with typos. Or grammar. Or even finances. Rather, the most daunting task was collecting photos from all of the seniors. Once the system of formal portraiture had been dismantled, reinstalling it became almost impossible. In 1974, editor Steve Block ’75 tried to lend order to the chaos, informing students in a Collegian article: “There is a photo booth at the Big N in Vernon. If you are a senior and want your picture in the yearbook, have your picture taken in their booth, and then turn in the strip ... The 50 cents will be refunded.”Five years later, the problem of getting students to participate had only grown. Editor Cheryl Ririe ’80 excoriated her classmates in a 1979 letter to the Collegian, noting that most had missed the deadline for submitting photos. “To date, there have been 90 pictures turned in—less than 1/3 of the class total,” she noted. “[And] 15 of those have to be reprinted due to poor print quality.”

Predictably, the publication has come and gone in recent decades as student participation has ebbed and flowed. The 2006 edition of Reveille opened with the words: “Guess who’s back?”

The 2014 issue of Reveille will be the first edition produced that doesn’t involve students. Last fall, when it became apparent that no students were likely to undertake the project, two Kenyon staff members volunteered to cobble a book together. “I worked on the yearbook in high school,” said one of the volunteers, Pamela Faust, executive assistant to the president and provost. “I thought, ‘At least I can check the names.’”

Faust and Kim Blank, assistant director of student activities for programming, arranged to have seniors photographed at the annual Graduation Fair and collected photographs from students, coaches, and professors as the year went on. Jostens, the yearbook company, will design the cover and print the book. Priced at $85, it will mostly be sold to seniors and parents. Staff will also retain some copies for archival use.

Why the lack of student interest? Some say Facebook has replaced yearbooks. “There’s no reason for me to have a print copy of all these photos, because they’re all on Facebook anyway,” says David McCabe ’14, coeditor of the Collegian, echoing the likely sentiments among his classmates. But Leland Holcomb ’14, senior class president, isn’t so sure that the world’s largest social networking site serves the same purpose as a yearbook.

“Certainly you can go to Facebook and find pictures of individuals,” Holcomb said. “But I think the purpose of a yearbook is to have classes and groups together.”

Yearbooks once reflected the intimacy of the college experience, observed Lauren Toole ’14, the Collegian’s other coeditor. As schools like Kenyon have gotten bigger and grown more diverse, perhaps capturing the essence of that experience in a single publication has become too difficult. “You flip through a yearbook to look at a collection of snapshots and memories, but as the Kenyon community has grown larger, those moments that involve the entirety of campus are less frequent,” Toole said. “In high school, the majority of the student body attends the winter formal, prom, homecoming—memories that nearly everyone can share. We have fewer of those types of traditions at Kenyon.”

Art professor Spaid, for one, thinks the arrangement of having staff work on the publication is, in principle, a bad idea: Student publications should be produced by Kenyon students. “It’s just another aspect of the kind of handholding we do,” he says. “And it deprives the students from having an experience like I had, which is to do a fairly significant piece of nonacademic work.”

Lily Moore-Coll ’07, who edited the yearbook in 2007, agrees. Working on Reveille, she said, gave her a whole different picture of Kenyon. “I was really grateful for that. It expanded my whole view and knowledge of the College. I feel a different sort of passion for it now.”

“It’s a shame,” said former editor Berlow. “It would be a great opportunity for someone to make a statement.” But he also acknowledges that Facebook, Instagram, and other photo-sharing sites may have lessened the need for yearbooks as a repository of photographic images and memories. “When you can have a photograph of anything, maybe no photograph is particularly important,” Berlow said.

Spaid would like to see Kenyon rethink the yearbook. Funding for Reveille could be used for some sort of student-produced project—a print publication, an electronic one, or something else—that depicts life on campus, much as the original Reveille set out to do. Students could use the occasion to experiment. They could leverage the project to make a statement.

So opportunity knocks again. Will anyone heed the bugle call?

Joel Hoekstra is a freelance writer who lives in Minneapolis.

Kenyon’s land trust turns a golf course into a public nature preserve—including space for environmentally friendly…

Read The StoryA reigning force on the young-adult best-seller list, Ransom Riggs '01 pulls in readers with haunting imagery and…

Read The Story