A Natural Evolution

A conversation with outgoing president Sean Decatur about science, higher education and his groundbreaking new…

Read The StoryWhy Paul Newman is having a moment. Again.

Story by Eileen Cartter '16

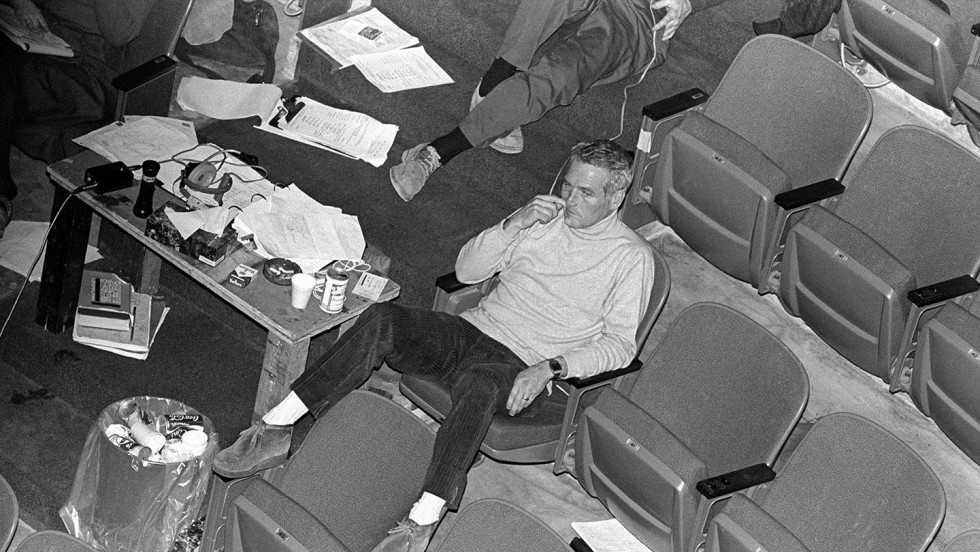

In the opening moments of “The Last Movie Stars” — a six-part HBO documentary series profiling the lives and legacies of Hollywood greats Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward — the project’s director, actor Ethan Hawke, recalls his first memory of Newman: Hawke was a 10-year-old kid growing up in Fort Worth, Texas, when, on one hot summer Sunday, his dad suggested they play hooky from church to catch a matinee revival of a cowboy picture called “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.”

“And from that day forward,” Hawke narrates, “the movies have been the church of my choice.”

“The Last Movie Stars” is one of two major retrospective works about Paul Newman ’49 H’61 to emerge in the past year, the other being a posthumous memoir, poignantly called “The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man,” published by Knopf. Both projects were gleaned from hundreds of hours of recorded interviews that the actor and his friend, “Rebel Without a Cause” screenwriter Stewart Stern, conducted among key players in Newman’s life between 1986 and 1991, ostensibly for a future autobiography. (There also is a striking, though unrelated, new photobook of Newman, called “Blue-Eyed Cool.”) As the story goes, Newman himself set fire to the audiotapes in the late ’90s — but not before Stern had transcribed them all. In 2019, nearly a decade after Newman died of cancer at age 83, a friend of the family found the transcripts locked away in filing cabinets in an old storage unit — the place where all lost things go.

The docuseries, which examines Newman and Woodward’s enviable, complicated 50-year marriage amidst their dovetailing careers, was a project Hawke took on at the request of the couple’s youngest daughter, Clea Newman, who also had a hand in the memoir’s publication. (Woodward, now 92, has been living with Alzheimer’s disease since 2007.)

Both stem from the notion that, at one point in his life, Newman wanted, in his words, “to leave some kind of record that sets things straight, pokes holes in the mythology that’s sprung up around me, destroys some of the legends, and keeps the piranhas off, (because) what exists on the record now has no bearing at all on the truth.”

It’s an interesting time to look back on a classical industry legend like Newman, a person of a time and place we most certainly hail from but can never return to again.

What, then, to make of this “Newmanaissance,” as actor Josh Radnor ’96 terms it? Here is a beloved man who was, in some sense, interested in demolishing his own mythology. Who, at least at one moment in time, urged us to reconsider who he was and how we saw him. In any case, Newman probably understood that legacies are often shaped by the memories and stories that others share — and that the reasons for which we attach meaning to someone else’s legacy are constantly changing. All of which is to say, we probably ought to re-examine how we regard legends in the first place.

“If you go to Kenyon and you become an actor or go into the arts, the Newman lore and mystique is unavoidable,” Radnor told me by phone. Like Newman, Radnor’s parents are from Cleveland, and his father, Alan Radnor ’67 P’96, ’00, also went to Kenyon. He remembers seeing a framed photo of Newman in the Shaffer Speech Building, home of the Hill Theater, and feeling a connection across space and time, comforted by the idea “that he performed on the stage of the Hill where I performed so many times, that he probably had classes in Ascension Hall, that we walked the same Middle Path.”

“I took some comfort in the fact that he went there and I went there,” said Radnor, who starred in the CBS sitcom “How I Met Your Mother” and later returned to Gambier to direct his 2012 film “Liberal Arts.” “Even if the actual person felt very far away, and the myth overtook the man in some ways.”

In his memoir, Newman’s mythical Kenyon days read more like a bawdy parable.

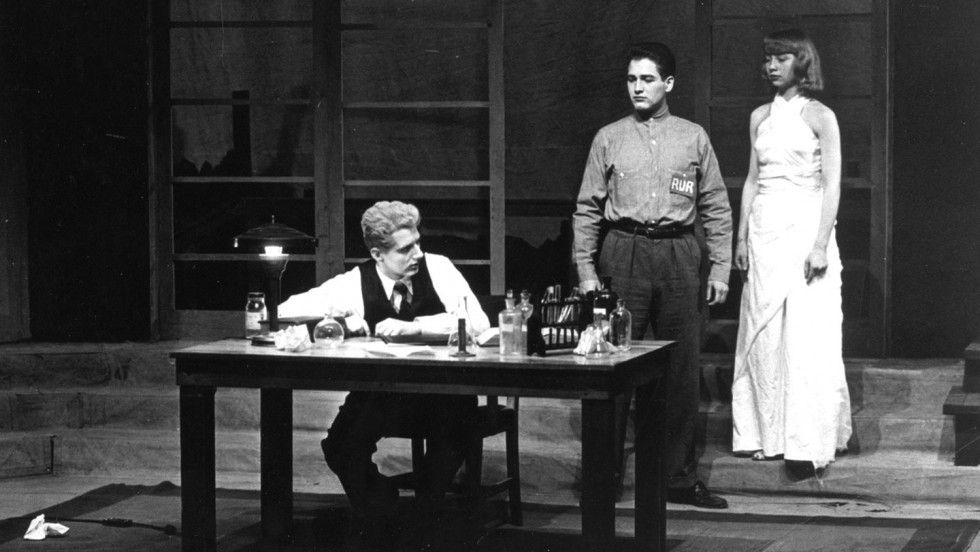

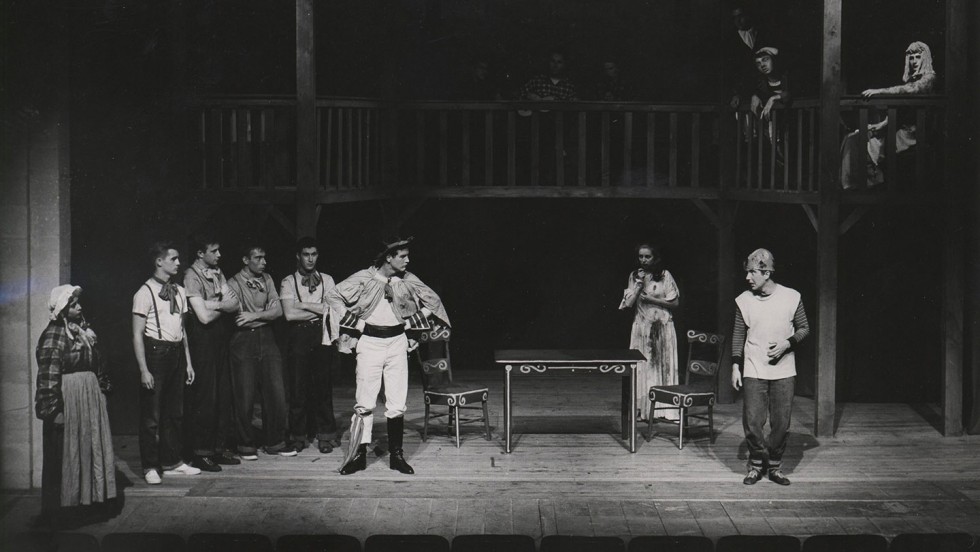

“The incredibly stupid mistake I made coming out of the war, having not been shot down in the Pacific, was signing up for a non-coed school like Kenyon College,” Newman regaled in the memoir. “I thought what I wanted, even more than women, was a good education.” He turned to theater after getting kicked off the football team; his directors had a hard time not casting him as the lead. He received this with his usual self-deprecation: “I never regarded my (undergraduate) performances as real successes; they were just something that was done, nothing more important than someone working hard and getting an A in political science.”

One year, he founded a clothes-washing service called Newman’s Laundry and Dry Cleaning Service out of an empty storefront on Main Street in Gambier; to promote it, he offered customers a free beer with each load. His senior yearbook blurb in the 1949 Reveille read: “Prone to getting out of hand on long and trying evenings.”

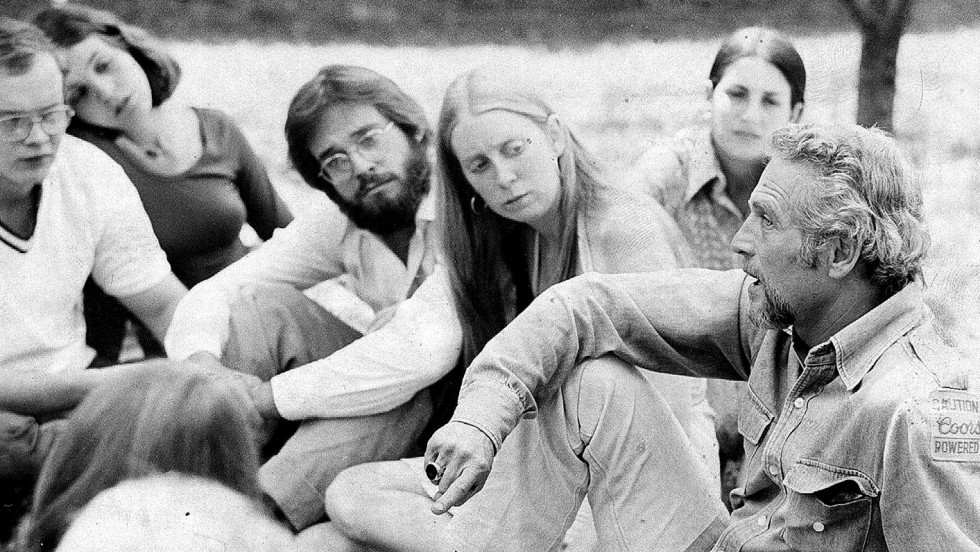

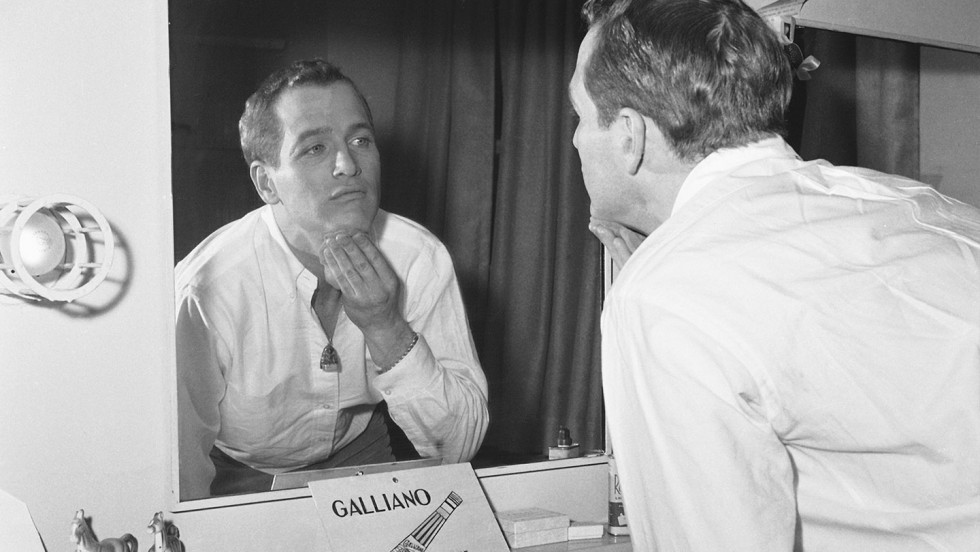

On campus, Newman’s legacy is all around. It fills the rafters of the Hill, where he starred in nine theater productions, but it also at times persists in the clandestine celebration of Newman Day, during which a quote is often attributed to him — “Twenty-four beers in a case, 24 hours in a day. Coincidence? I think not” — though Newman himself repeatedly disavowed both the practice and the attribution. (He purportedly addressed the student body in a 2005 email to President S. Georgia Nugent that included the line: “I lost a son to alcohol/plus other stuff. The thing is — he started out just as harmless as any of you.”) In 1978, Newman returned to Gambier to christen the new Bolton Theater with its inaugural production of “C.C. Pyle and the Bunion Derby,” whose cast featured then-student Allison Janney ’82; the following year, he and Woodward came back to help establish a summer-stock theater company. For decades now, every year during Honors Day, the drama department has awarded its top actors — including Radnor and Janney — trophies named in Newman and Woodward’s honor, creating a daunting lineage of legacy characters.

By all accounts, in theater and certainly otherwise, their generosity was boundless. Paul and Joanne nurtured fellow actors all their lives. After “C.C. Pyle,” Newman saw something in Janney: “I must have done something that impressed Paul,” Janney previously told the Kenyon Alumni Magazine, “because he told me: ‘If you ever need a favor, you can ask me for it — it has to be specific, so don’t waste it!’ I actually never asked him for anything, but it gave me confidence knowing he believed in me.”

What’s more amazing, in the nearly 75 years since Newman attended Kenyon, is that so many people in the Kenyon orbit still seem to have a Newman story: some instance of seeing him around, or knowing someone who did, “even if it was second- or third-hand,” laughed College historian Tom Stamp ’73. There always seems to be “some reference to having had a sighting or sitting at the table next to his in a restaurant, or at the stool next to his at a bar,” said Stamp. Last July, I went with two fellow Kenyon alumni to a screening of “The Last Movie Stars” at Film Forum in New York City, which was followed by a Q and A with Hawke. Unsurprisingly, there was another alum in the audience — I wish I’d gotten his name — who shared a story about his mother feeling completely over the moon to see Newman walking across campus at an alumni event.

“There’s no denying that he was remarkably handsome,” Stamp said. “I mean, you would stop dead when you saw those eyes, especially.”

Perhaps saying you once saw Paul Newman is like saying you went to Woodstock in ’69; it hardly matters if it’s actually true. But for a small village in central Ohio, the quantity of stories alone helps Newman seem, as Stamp put it, “life-size and larger than life at the same time.” Newman was a real-life celebrity — but he was also a Kenyon celebrity.

Chris Eigeman ’87, a director and actor best known for performances in Whit Stillman’s “Metropolitan,” “Barcelona” and “The Last Days of Disco,” as well as Noah Baumbach’s “Kicking and Screaming,” and a recurring role on the TV show “Gilmore Girls,” described meeting Newman in person before he passed away, saying that his presence felt both enormous and gracious. “It’s not lost on anybody that he was a huge movie star and that just makes its own weather,” said Eigeman — who, like Radnor, was a Mr. Paul Newman Trophy winner at Kenyon.

Time, however, remains the only constant: Stamp, as well as College archivist Abigail Tayse, who frequently fields media requests for Newman-related materials from Chalmers Library’s digital archive, say they’ve observed fewer and fewer current Kenyon students each year who seem to have a concrete sense of who Newman is. Or, if they are familiar with Newman, it’s not because they know his filmography. It’s because they know his salad dressing.

Among all his other qualities, Newman was also, apparently, a stickler about homemade vinaigrette. He was known to gift friends and neighbors with his own proprietary brew that would become the cornerstone product of his charitable food company, Newman’s Own, which he founded in 1982 with his friend, writer A. E. Hotchner. What began as a simple if chaotic enterprise (as the story goes, Newman and Hotchner first set up shop in the barn at Newman’s house in Westport, Connecticut, and mixed up a vat of the stuff using an old canoe paddle) grew into a multimillion-dollar non-profit empire of jarred pasta sauce, frozen pizza and microwave popcorn, among other things. Newman donated the net proceeds to various organizations benefiting children. In 1988, Newman founded the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp as a getaway for children with serious illnesses and their families.

In his memoir, Newman determined that “the most barometric incident in my college life was entrepreneurial, not theatrical: it was my laundry business.” Later in his life, he shifted the course of his own legacy, refashioning himself from actor to entrepreneur once again — though this time, Newman’s success as a salesman was buoyed not by free cans of beer but, in part, by the warmly rendered illustrations of his famous face on its packaging. “The younger generation doesn’t buy the stuff because of me,” a then-78-year-old Newman told the New York Times in 2003. “They don’t even know me. I think they buy it because of the charity.”

Miriam E. Nelson, former president and CEO of Newman’s Own Foundation, hopes the world remembers Newman for being “radically good” well ahead of his time. For the ways in which he worked “to make the world better, to use the influence that he had to show up and support people and organizations,” she told me. “And I do hope that, you know, people remember that he was absolutely stunning, and that he channeled that. He used it all. He used every one of his assets for good.”

Of all the times Nelson has found herself in Westport, where the foundation is headquartered, there hasn’t been one when somebody didn’t share with her a Newman anecdote. “He stopped traffic — well, he always stopped traffic — but to help people cross the road,” she said. The owner of a local house Nelson rented in town shared his story that, as a young kid, he used to indulge in some stealthy trout fishing in a stream on the Woodward-Newman property. Once, a gleeful Newman spotted him, and then promptly invited him inside the house to fry them up.

Whether or not “The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man,” or its source material that animates Hawke’s documentary, lays bare those things in the way Newman himself would have wanted is itself a complication, or a function, of legacy. Lest we forget, Newman himself burned the tapes, perhaps having grown resentful or ambivalent to the whole idea of revisionist history. And yet our stories find ways of getting told, even when we’re not around to supervise.

There’s a cosmic equilibrium to this. “The years go by, and we’re all going to be misremembered and then forgotten. And I take some comfort in that, in a weird way,” Radnor told me. “I feel like part of the beauty of life is that it’s lived in the present, and we flicker as bright as we can or are meant to, and then we make way for other generations. But I do think, if you’re interested in acting and you’re interested in film and you want to see it done at some of the very highest levels, there are these movies that this guy Paul Newman made that are worth checking out.”

As far as reasons go for a Newman cultural resurgence, Eigeman admitted he “(doesn’t) know what gave rise to this. I’m certainly grateful for it. I’m always happy to hear about Paul Newman. You could try to make an argument that there was a deep sense of decency about the man, and that has been in short supply at times.” It helps, he added, that Newman had “such vibrant, eye-catching hobbies. I like to cook, but I’ve never been behind the wheel of an F1 sports car.” Eigeman recalled once sitting at the Kenyon Bookstore when he was a student, reading a magazine article about Newman in which he mentioned having a sauna in his house, and a ritual and a ritual of going down to said sauna in a pair of cutoffs with a can of beer and the New York Times; eventually, he’d emerge from the sauna with an empty beer, covered in newsprint.

“And I was like, ‘That’s something I can emulate,’” Eigeman laughed. “‘I want to get to a point in my life where I have a sauna and can go down with a can of Budweiser and a newspaper and be left alone and come out looking like a ragamuffin.’” Eigeman paused for a moment: “I guess he actually did loom slightly larger than I thought he did.”

It’s stories like that, about legacies like Newman’s, that coalesce into a broader public discourse about the death of the monoculture: the aching sense that we’ve lost all previous notion of a unified mass audience, fractured by the internet’s burden of choice. Hawke’s documentary title is a reference to a characterization about Newman and Woodward from their friend, writer Gore Vidal, who said they were the last to come up in the classical way that the Golden Age stars did: taking classes at the Actors Studio, working within the confines of the old studio system.

Kathryn VanArendonk ’07, a Vulture television critic who reviewed “The Last Movie Stars” for New York magazine, briefly worked in the library archives during her senior year at Kenyon. There, digitizing the College’s historical ephemera, she got a solid sense of the key figures in Kenyon lore: “It was Philander Chase and Paul Newman, and then everyone else.”

Nowadays, that sort of rarefied ground feels like a relic in itself.

“In spite of how remarkably prolific he and Joanne were, the fact of his stardom, and the intensity of the myth around him meant that he was not a person (you) felt like you knew. They were not a friendly constant presence in your home in the way that a TV star was at the time,” said VanArendonk, though she noted they had both acted in television roles. That mythological “separateness, between who they are and the work that they do, and the person that their audiences see and don’t have access to,” can be mighty useful to a movie star’s career. “At the same time, it can be so corrosive, this knowledge that this viewing audience sees you one way and (you) need to maintain that wall of who you are.” Whatever spiritual membrane that once shrouded celebrity as “untouchable” has long since worn out.

Last summer, in the aftermath of the ultimate Tom Cruise victory lap that was “Top Gun: Maverick,” the Times critic Wesley Morris considered the end of movie stardom. He pointed out that Cruise, who turned 60 this past July, is now one year younger than Newman was when they acted together in “The Color of Money” (1986), the performance for which Newman finally won his Oscar — the eighth nomination of his career.

“Newman was 61, which is nothing like Cruise’s extraterrestrial 60. (Newman) is gray, with wrinkles and some creaks,” Morris wrote. “There’s history in those creases: reserves of sadness, loss, disappointment, shame, hurt, loneliness, eased along by cigarettes and booze. For a veteran star, these are virtues. Currency. And the movie compels you to appreciate the accrual of time — the decades he’s lived, the decades we’ve lived alongside a version of him. How much had he changed? How much had we?”

Hawke, speaking on an episode of the “Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso” podcast that Radnor had recommended, recalled a favorite memory during the making of “The Last Movie Stars.” Actor Sam Rockwell, who voices frequent Newman director Stuart Rosenberg in the HBO doc, hadn’t seen 1973’s “The Sting” in years but suddenly remembered a hyper-specific Newman moment from it: Newman’s character, Henry Gondorff, wipes his mouth with his necktie after a sneeze. A brief gesture, sure — but are those gestures, these bits and bites of performed personhood, not a reason to love movies in the first place?

“These things are a part of us. They live inside of us,” Hawke emphasized. “We are carrying on these torches and fires that are lit from generations before, and if that’s true, then what we do today matters to the future. And not just to your kids — (to) your friends, your people, the people you see tonight at dinner. All of it is happening in the present tense.”

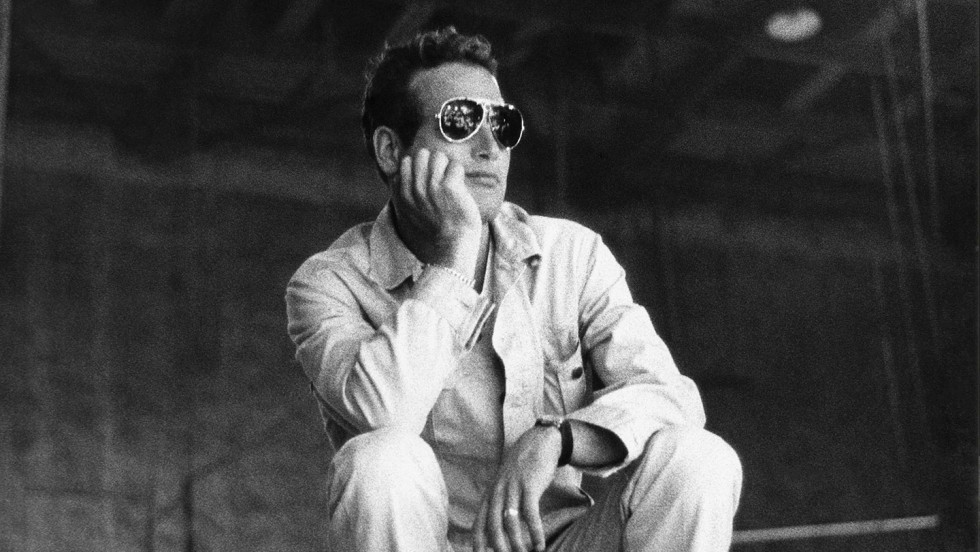

Newman was always highly critical of his own talent, the choices he made and the advantages he had along the way. (His self-criticism is not always unmerited, but it is quite harsh.) He, a self-described “emotional Republican,” was a generational success as an actor, director, race car driver and philanthropist, but self-doubt followed him always. In the black-and-white photograph that covers the memoir, Newman gazes out from behind the palm of his hand, obscuring most of his famous face and one of his famous blue eyeballs. “I picture my epitaph,” he once said. “‘Here lies Paul Newman, who died a failure because his eyes turned brown.’” Wildly enough, Newman himself was color-blind.

Eileen Cartter ’16 lives in Brooklyn, New York, and is a staff writer at GQ. At Kenyon she was a member of the Gund Gallery-partnered, extracurricular film club Cinearts, and the first movie they screened during her senior year was “Butch Cassidy amd the Sundance Kid.”

A conversation with outgoing president Sean Decatur about science, higher education and his groundbreaking new…

Read The StoryThe art (and math) of building a bookshelf bucket list.

Read The Story