Farm Folk

Set aside the stereotype of the farmer as a man wearing overalls and a straw hat, perched atop a tractor by a cornfield…

Read The Story

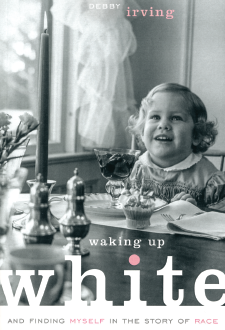

It’s no secret, or shouldn’t be, that race still matters in the United States. But many whites think explicitly about racial issues only when they erupt—when, say, the shooting of an unarmed black teenager ignites protests and debate.

This book is about how race has long mattered in more pervasive, and pernicious, ways. Waking Up White, by Debby Irving ’83, is both a racial autobiography, unsparing in its self-examination, and a tutorial in the history and corrosive impact of white privilege. With eloquence and a sense of urgency, Irving takes us on a journey into the heart of what is arguably the American issue.

Irving describes her privileged childhood in the almost exclusively white Boston suburb of Winchester, Massachusetts, a “monocultural world” that instilled in her an assumption that “accomplishment for anyone was simply a matter of intention and hard work.” The idea of “unearned privileges” was “an unfamiliar concept from an unknown American reality.”

After Kenyon, she worked as a Boston-area arts administrator, often on programs connecting inner-city children with cultural events—and was naively surprised to learn that her efforts weren’t “fixing” their lives, or necessarily even welcome. As a young mother in Cambridge, she sought out diversity but “ended up surrounded by white people.” And as a parent volunteer and then assistant teacher in a progressive, inclusive Cambridge elementary school, she was disheartened to see how, by fourth or fifth grade, the white children were outpacing their black peers in academics, engagement, and leadership.

All the while, though increasingly frustrated by her inability to connect with African Americans, she continued to believe that “I can help people of color by teaching them to be more like me,” and that racism is only about “bigots who make snarky comments and commit intentionally cruel acts.”

The turning point came in a course called “Racial and Cultural Identity,” which she took while pursuing a master’s degree in special education and which produced revelation after revelation. She learned, for example, that because of discriminatory practices, blacks reaped few of the benefits of the G.I. Bill, the post-war program offering so many American families a boost toward security and prosperity. It made her angry and ashamed to think that she had been “an unwitting player” in a system of “affirmative action for white people.”

She realized, moreover, that her privileges gave her, in addition to material advantages, “a whole host of intangible benefits” like optimism, confidence, and trust in American institutions. “My life had been built on more than a diploma, a paycheck, fresh fruit, or medicine when I needed it; it had been cemented with a sense of access, belonging, and optimism”—feelings that she took for granted but that many blacks didn’t share.

The most unsettling discovery was that being a “good person” was in a sense beside the point. To truly grapple with racism, she had to go beyond understanding others; she had to turn the lens on herself. “I thought white was the raceless race—just plain, normal, the one against which all others were measured.” “Racial identity,” she found, was about her, not just about “others.”

Irving weaves her personal story into a discussion of issues such as the role of race as opposed to class in discrimination, the understanding of race as a “social construct” rather than a “biological certainty,” the importance of “normalizing race talk” rather than avoiding it, and the value of “rethinking assimilation.” She asks: “Isn’t the more intelligent choice to create a culture built around difference?”

She describes embarrassing moments in workshops and conferences as she made it her mission to challenge “the comfort of my white world of clear-cut rules so I could learn to navigate multicultural waters.” Her journey led her, ultimately, to become a facilitator in a Cambridge adult education workshop called “White People Challenging Racism: Moving from Talk to Action.” And, of course, it led to her book.

“I can’t give away my privilege. I’ve got it whether I want it or not,” Irving writes. “What I can do is use my privilege to create change.”

Waking Up White is a provocative, persuasive call to action. Readers may squirm at some of its arguments, but they will find themselves thinking—hard—about them. And they will take them to heart.

(CRC Press). Written for health-care professionals who treat patients with asthma, this comprehensive study includes case studies and contributions from leading experts. Bernstein, a professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, is editor of the Journal of Asthma.

(Adams Media). The goal is simple: a secure retirement. Birken’s book presents detailed strategies for getting there. A finance writer and blogger, Birken covers every aspect of retirement, from housing to health care expenses.

(Rowman & Littlefield). This activity-packed resource for high school teachers is built around a series of key questions embedded in To Kill a Mockingbird, along with contextual readings ranging from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first inaugural address to the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia, which struck down laws prohibiting interracial marriage.

(both Talos Press). Kenemore’s inventiveness and narrative verve are on full display in these two horror novels. The first, through a series of interconnected stories, pulls us toward a hotel’s hidden secrets. The second—like its predecessors, Zombie, Ohio and Zombie, Illinois—blends suspense (and, yes, zombie brutality) with deft characterization, page-turning action, humor, and heartland politics.

(Schiffer Publishing). A photographer and film director who works in both journalism and the corporate world, Kittle has produced a thought-provoking art book. He photographed a white porcelain Buddha in diverse, sometimes unlikely settings—in cities as well as in nature—and pairs the photos with quotes from figures ranging from the Dalai Lama to Proust. The pages offer meditative moments, quiet irony, and—always—beauty.

Needle shows digital camera (and smartphone camera) users how to create “impressionistic” effects with long-exposure, multiple-exposure, and other techniques. An award-winning flower and garden photographer, Needle is also the author of an e-book, Creative Macro Photography: Professional Tips & Techniques.

(Lowertown Press). “The good news is: you will be OK. The bad news is: this is only the beginning.” Remke, a clinical social worker and palliative care specialist, offers valuable advice for coping, infused with compassion.

In these short essays, based on her own experiences and those of other women, Steffy takes on serious subjects—including aging, body image, and confidence—but often with wit. Steffy writes the blog “Dating in L.A. and Other Urban Myths,” and is working on a video web series based on the L.A. dating scene.

(Kindle e-book). Wachtel has had careers as an Air Force pilot as well as a medical researcher specializing in genetics. His expertise in both realms contributed to this sci-fi adventure in which cybernetic marines battle genetically enhanced warriors.

Set aside the stereotype of the farmer as a man wearing overalls and a straw hat, perched atop a tractor by a cornfield…

Read The StoryDelving into the history of design and material culture, a journalist-scholar discovers the humble dinner dish…

Read The StoryAfter a decade of intense construction, Kenyon’s master plan gets a remodel of its own.

Read The Story