How to Have a Conversation

Kenyon alumni and faculty explore how to become better communicators.

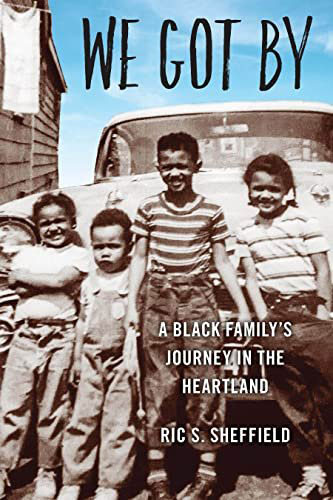

Read The StoryProfessor Ric Sheffield's new memoir reaches across four generations of his family.

Ric Sheffield is no stranger to deep dives into historical research. For the past three decades the emeritus professor of sociology and legal studies has studied and shared stories about the Black experience in rural America.

Kenyon students and alumni might recognize Sheffield from his class, “Diversity in the Heartland,” where students conduct community-based research projects — some of which are so impactful that they result in historical markers being placed at important sites, such as Mount Calvary Baptist Church, a prominent Black church in Mount Vernon, Ohio.

More recently, Sheffield focused his attention and research skills on his own family while writing his memoir, “We Got By: A Black Family’s Journey in the Heartland.” The book reaches across four generations of Sheffield’s family, nearly all of whom grew up in Knox County, on a plot of land in Mount Vernon where each branch of the family tree built a house. Yet as one of only a few Black families in the area at the time, they experienced a simultaneous juxtaposition of invisibility and hyper-visibility that Sheffield explores in “We Got By.”

Sheffield is on a mission to educate, inform and correct stereotypes about Black and other people of color in rural communities by speaking and writing about rural diversity. He’s given talks in close to half of Ohio’s 88 counties, the majority of which are rural.

After his talks, “time and again people would say to me, ‘This is really interesting. I’ve never really thought about this because I’m not sure if we have any Black people who live here.’ And I’m always quick to say, ‘That you’re aware of or that you noticed — because there probably have been Black people here for generations,’” Sheffield said. “Particularly post-slavery and the Great Migration with Black folks moving up north, this notion of invisibility is both a consequence of low populations but also by strategy. You can imagine that Black folks, especially those who migrated out of the South, came to believe that drawing attention to yourself is not a good thing. That it’s quite likely that that attention will bring some undesirable consequences.”

However, as Sheffield is quick to share in “We Got By,” it’s not all gloom and doom for Black residents of rural communities. There’s an abundance of joy to be found — from home-cooked, communal meals to horseback riding and stargazing on dark country nights.

“When I’m leading students and doing these sorts of projects, I say to them, ‘You are accountable to the whole range of human experiences,’” Sheffield said. “And, yes, there will be some tragic stories and a lot of sadness. But you have to balance that with the stories of joy and celebration; of pride and perseverance.”

Black joy, especially rural Black joy, is rife throughout “We Got By,” though that isn’t to say that Mount Vernon and its white population always loved Sheffield back. In particular, 1968 was a difficult year. Black America was stunned by the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and that year brought even more personal tragedy to Sheffield’s family when his uncle and aunt were killed by a white woman determined to prevent her son from marrying into their family. Like many Black youth of that era, he was determined to move away from a town that seemed not to understand how much racial conflict had marked his life. Eventually, he went to college in Cleveland and became a trial lawyer in Columbus, and worked as an assistant attorney general for the state of Ohio.

Eventually, city life wore on him, so when he and his wife decided to buy property — hopefully with some land and a barn that could be converted into an art studio for his wife, Ellen — they found themselves back in Knox County. Then, in 1989, Sheffield was hired as a faculty member at Kenyon — a college with which he was familiar because his grandmother once worked as a domestic for a professor and administrator there.

While things have changed considerably since Sheffield was a kid in rural Ohio, there’s always more work to be done to promote racial understanding and respect for difference.

“I was in the grocery store in Mount Vernon standing in the produce section and I noticed this older white fellow staring at me,” Sheffield said. “When he got close enough to say something to me, he said, ‘You’re not from around here, are you?’... I was thinking, ‘What is it about me that makes him conclude that I’m not from around here? Oh, I don’t look like him and almost everyone else in the store.’”

As he so often does at his talks at historical societies throughout the region, Sheffield issued a gentle correction.

“It was obvious,” Sheffield said, “I don’t look like I belong here because of the color of my skin. If you spend a lifetime being reminded of just that fact then you develop a number of defense mechanisms: wariness and distrust, isolation, invisibility, self-consciousness, and conspicuousness. Those things are consequences of being one of the only, if not the only, in the community where you live.”

To prepare children for these encounters, Sheffield spoke of what’s often called “the talk”— a conversation families have to help their children understand race and racism. While the talk is commonplace in Black families, Sheffield is concerned that it’s not common enough in white families.

“When there are no conversations about race growing up, it teaches and confirms that your family doesn’t have to think about it. That’s what I conceive of as white privilege,” Sheffield said. “People are realizing that white privilege isn’t just that you have more stuff than Black people have — that you drive a better car or your job is more prestigious. Because in rural America, that usually isn’t the case. You don’t often have this stark contrast between the haves and the have-nots.”

“Just saying that,” Sheffield added, “I can hear my grandfather saying, ‘Son, your dark skin will enter the room before you even get a chance to.’”

Readers meet this grandfather, as well as Sheffield’s siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins and more relatives in “We Got By,” but the memoir is truly a love letter to his grandmother, Bertha Ruthanna Edwards Fisher Hammonds, and his mother, Oneida Mae Fisher Sheffield Lawson. Sheffield was able to share a couple of chapters with his mother before she died.

Post book-release, Sheffield’s research continues through other historical research projects he’s working on, including a multimedia presentation about Negro league baseball, specifically an all-colored team in Knox County, Ohio, that Sheffield’s class rediscovered, and a podcast series. For the podcast, he’s particularly interested in veterans who served in the military and how relatively unknown and unrecognized they are during Veterans Day ceremonies in America’s small towns.

These unsung heroes are never far from Sheffield’s mind, though he’s not only concerned with heroes — it’s everyday people who create the fabric of a community.

“I recognize that I’m one of the few people obsessed enough to want to pursue this that if I don’t do it, it may not get done,” Sheffield said. “You don’t have to be a hero or celebrity. You don’t have to do something that’s considered to be historically important. But the fact that people don’t recognize that you even exist is part of what propels me to want to give voice to people.”

Learn more about Sheffield at ricsheffield.com.

Kenyon alumni and faculty explore how to become better communicators.

Read The StoryThe history of the Village Inn, Gambier's iconic restaurant and gathering place.

Read The StoryA conversation with Mailchimp colleagues Michael Mitchell '03 and Lain Shakespeare '05.

Read The Story