The first stirrings of Philander’s Phebruary Phling came with playing cards dropped on the dining tables in Peirce Hall. The year was 1991, and on the cards were written the dates February 15-16. Anticipation grew when outsized dice were hung in Peirce without explanation.

“We didn’t tell anybody what was going to happen. The whole goal was to change the rhythm of February at Kenyon and make things unexpected,” planning committee member Andrew Keyt ’91 recalled. Mission accomplished.

The story hit the Collegian on February 14 that year. “It was actually pretty ingenious marketing,” said Amy Kover ’94, who wrote the piece. “There were titillating signs all over campus. Something awesome was going to happen.”

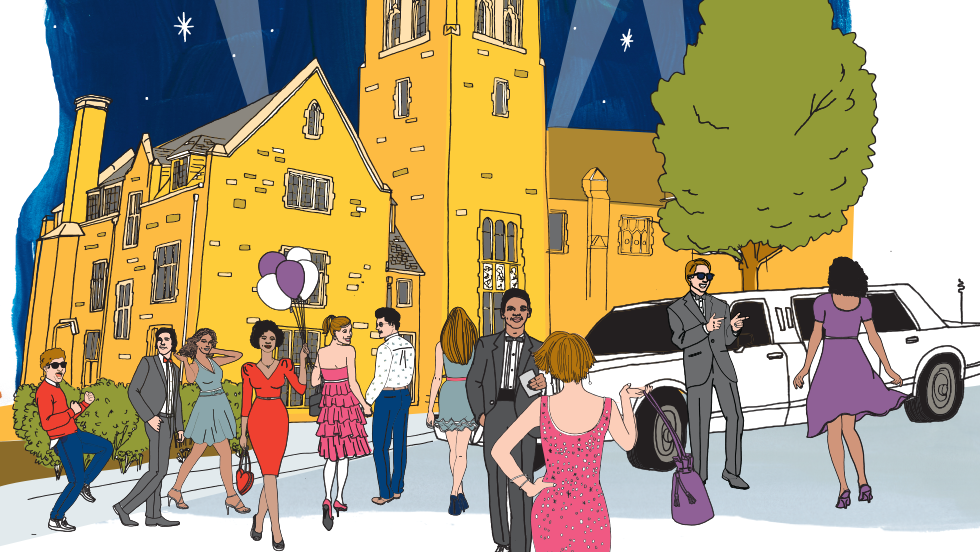

An epic, campus-wide, weekend-long event and formal party were launched, defying winter’s gloom and spawning twenty-one years of phonetic finagling. The annual rite of February finally succumbed after the 2011 event, a victim of Phling fatigue, dwindling student participation in planning and hands-on work, and the lengthening shadow of misbehavior. But Phling will ever endure in Kenyon history thanks to its hard-earned reputation as Kenyon’s premier party, a sprawling concoction of dance music, casino nights, and high heels—not to mention unbridled fun.

Fear not. The Class of 2014, nurturing the last vestige of on-campus student Phling memory, rallied in the spring semester to create Phling 2.0, an alternative version dubbed Philander’s Ball that they hope will pick up in its own way where Phling left off.

The partyers in 1991 had no idea Phling would be sustained for twenty-one years. The playing cards and dice, of course, hinted at the casino games that became a Phling staple. That year’s two-day event featured a pair of hot tubs outside of Farr Hall, limousine service, and a Friday black-tie dance with big-band music. The Chasers, Kokosingers, and Owl Creeks sang around the campus on Saturday. Bluesman Big Daddy Kinsey performed that night in Wertheimer Fieldhouse.

“Our goal was to change everything about the campus, to make it unexpected, as different from the normal life of Kenyon as we could,” Keyt said. “Friday was the casino night. We got businesses in Mount Vernon to donate prizes. I distinctly remember riding back from Mount Vernon in a convertible with the top down and a bicycle donated by K-Mart in the back.

“There was this huge buzz. Pretty much everybody on the campus came. The planning committee, we were upstairs in Peirce and we went on the balcony and looked out and we were just celebrating,” Keyt said. “It was a huge success.”

Not all plans were approved, though. A scheme to sub comedians for professors during Friday classes was vetoed. And ideas to name the event after President Philip H. Jordan Jr. and have him ride on the back of a flatbed truck to Phling were rejected. “I don’t recall that,” Jordan said, “and I’m very glad it wasn’t named for me.” Naming rights went, instead, to Kenyon founder Philander Chase.

Fond of February

The event, Jordan believes, “was a great thing.” The idea was hatched in conversations Jordan had with Charles Davison, a friend and a Kenyon trustee and parent. “People were talking about the dreariness of February,” Jordan said. “We chatted around and thought, ‘Let’s have a special party.’

“We got into conversations with students about it. There was a lot of brainstorming.” Davison donated money to create the event.

“He was very pleased,” Jordan said of Davison. “We thanked him so much for the idea.” Davison, a business executive who died in 2000, made his donation anonymous, but his contributions created the Davison Fund for Student Life. His son, Andrew Davison ’87, described his father as a quiet and modest philanthropist with a keen interest in higher education. In this case he hoped to inject “a little whimsy” into winter-bitten Kenyon. “He appreciated that it was a tough time of year, a lot of studying going on, waiting for spring,” Andrew said. “He was an incredible guy.”

And he launched an incredible party. Cheryl Steele, then the associate dean of students and now dean of co-curricular life and vice president of student affairs at Sweet Briar College, was a witness to party history. “It was so much fun watching the students have fun and come together as a community,” she said. “It was something to break the winter blues. They would come up with a theme every year. I always found the students at Kenyon to be very creative.”

Carnival, cruise, and hoe-down themes took their turns. A speakeasy ushered in “phlappers and phelons.” There was “A Night at the OK Corral,” “A Night at the Oscars,” “The Lost City of Atlantis,” and “Fables and Fairy Tales.” The trappings and sidelights of Phling reflected the trends of the day: karaoke and trivia competitions, strobe lights, ballroom dancing, a mechanical bull, massages, and a Velcro fly trap. Along the way came a techno rave, the “Screw-Your-Roommate Dance,” a Phling king and queen, Gilligan’s Island reruns, and midnight breakfasts.

A winter storm caused a Phling postponement in 2010.

“We remember so fondly February in Gambier, Ohio,” Paige Olson ’95 said in her best deadpan delivery. She chaired the planning committee for the 1993 Phling and remembers several months of work involving “the cafeteria, the school, the limousine service, the band.” The Mardi Gras theme that year involved plenty of beads and masks and New Orleans-style food provided by the cafeteria. “It made a whole weekend thing,” she said. “The whole scene was Mardi Gras.” She wore a sequined gown to the main event.

The sequined gown was still a good choice in 2000, when Erin Eckert ’00, who worked on the planning committee that year, wore a floor-length version. Four bands, with “four distinct types of music” including a big band and a salsa band, played on Saturday night in Peirce Hall. Karaoke on Friday night in Gund Commons included a gong used by judges. “You got gonged,” she said. “That got a little out of hand.”

She remembers Phling that year as “chaos and a lot of fun.” The “vast majority” of students showed up on Saturday night. “It was the thing to do. It was definitely something people looked forward to. There were no competing parties. It was an all-campus event, with people from all walks of life, a full cross-section.”

Eckert was disappointed that only a handful of students pitched in for the planning, decorating, and clean-up. By that year, the administration “handled the burden” of the organization.

The Fault in Our Phling

As the rookie director of student activities, Tacci Smith, now associate dean of students, encountered her first Phling in 2005. “A lot of money and time went into it,” Smith said. “We literally started planning in early October. A lot of time was spent on picking the theme. It had to be special. We had bands. We had casino games. We had a backdrop to get your picture taken. There was a giveaway, a picture frame or a glass.”

Decorating work started on the Thursday of Phling week. “They would go all out,” Smith said. “We transformed the Great Hall one year. We had light strands that made a ceiling of stars.” A detour to the Kenyon Athletic Center (KAC) meant the building of a castle and drawbridge to match the fairy-tales theme. Some props were constructed, others rented. “Visually, it became a huge event.”

Budgets in that era typically fell in the range of $10,000 to $15,000, plus vendor donations valued at about $3,000. Casino prizes included flat-screen televisions and cameras. But no single student organization took ownership of the event, and the planning and hands-on work fell increasingly to administrators. Student planning committees that once numbered fifteen dropped to four.

And attendance gradually faded, although a hearty 800 or so turned out for the final Phling. But by that year, 2011, it became apparent that “this was too much work” for the staff, Smith said. “It was a really neat event,” Smith said. “But then it got disheartening.”

Alcohol consumption had been an unofficial theme from the party’s origin. “It wasn’t a sober event, definitely not,” Kover ’94 recalled, but the “substance-free” also showed up and had a good time. Eckert ’00 said, “It’s hard to believe there is more drinking now than there was then.” Kenyon is not unique in having students overindulge in alcohol, Steele said. “Students have always consumed alcohol. It was nobody’s fault, but it started to get more extreme. We had to staff it more. The world changed. Extreme behavior changed.”

The limousine service was dropped after an antenna and a window were broken and scratch repair and interior clean-up were required in 1994. “We decided then to resort to shuttles,” Steele said.

“They trashed the limousines,” Director of Campus Safety Robert Hooper said. He was on hand for every Phling. “I think for the majority of the students, it was a night for them to dress up, have a great time, enjoy the music.” Some students needed extra attention. “I would say, year in and year out, those who had to go to the hospital because of alcohol poisoning were in that four-to-five range. I remember one year we had three squads on the campus at one time.

“You had twenty that we got to their rooms and had somebody stay with them, and those were the ones we knew about. That’s the scary part.”

Safety officers were assigned to circle Peirce to look for stashes of alcohol and fallen students.

Some students started “pre-gaming” alcohol after lunch but “some would wait for dinner,” Smith said. Administrators grew weary of turning away intoxicated students at the door and mopping up messes on restroom floors. Some professors refused to volunteer, telling Smith, “I don’t want to see my students drunk.” Her response? “Well, none of the rest of us want to see them drunk, either.”

And, yet, many students behaved well, Steele said. “Why punish the students who aren’t doing anything wrong? We believed we could somehow model good behavior.”

Phling was clipped to one day in 2007, and remodeling in Peirce that year and in 2008 pushed the event to the KAC. A sit-down, catered dinner was arranged when Phling returned to Peirce in 2008 as a way to encourage eating before drinking. Student Council rallied for planning and organizing in 2010 and 2011, but the group is not built for programming and became daunted by the work load.

After lengthy discussions in the Student Affairs Division and with input from counselors, coaches, and safety officials, Smith pulled the plug after the 2011 event. Too little student help, a sense of waning interest, and the shiver of misbehavior added up to a firm decision. “I try to be very open about it,” she said. Aspects of Phling caused “anxiety and nerves” for her.

New Wave

Nina Zimmerman ’14 is part of the last class on campus to get a taste of Phling, an event that was much anticipated by her classmates but perceived by upperclassmen as a bit overrated. In film terms, Phling had become “a cheesy cult classic,” she said. “You love it for what it is.

“For us, it was an opportunity to dress up, go out, and have fun,” she said. “It was pretty fancy. When you’re a freshman girl, it was a lot of fun to get together with your hall mates and all get ready to go, and then take pictures and stuff like that. A big, formal occasion is a really nice thing to have. It was something to throw yourself into.”

Arriving sober was out of fashion. Zimmerman danced in Thomas Hall while mindful not to cut her bare feet on flattened cans of beer that had been smuggled into the building. “As a typical freshman you have that mindset that you have to get totally wasted to have a good time. As you get older, you realize that’s really not true.”

The Senior Class Committee, led by class President Leland Holcomb, had it in mind to resurrect a Phling-style event, and the feel-good, all-campus inauguration gala in honor of President Sean Decatur on October 26, 2013, provided a spark. “It made us remember what having a bigger thing was like,” Holcomb said. “The goal is not a frat party, just a community event.”

Philander’s Ball debuted in the KAC on February 15 as a semi-formal, all-campus dance. This year, with $10,000 from the Davison fund, Student Affairs directed support to the ball and five other February events hosted by various student groups—a crafts festival and Chinese New Year celebration among them—in the winter-spurning spirit of the original.

“It’s like an old wave of tradition kind of died,” Zimmerman said, “and a new wave is starting.”