The Other College Philander Built

A writer visits the site of Jubilee College in Peoria, Illinois, and finds the spirit of Kenyon’s founder is…

Read The StoryWhat it takes to create a classroom where everyone can thrive.

Story by Lisa Rab | Photography by Rebecca Kiger

Growing up in New York City, Katya Naphtali ’23 collected worms from parks and barcoded them to learn about ecology. Naphtali, who uses they/them pronouns, loved conducting research projects, but their high school didn’t have a strong science and math program. Naphtali initially struggled at Kenyon. They weren’t accustomed to taking exams, hadn’t taken any Advanced Placement classes and weren’t sure how to study all the new material. “It made me feel like I shouldn’t be doing science. Maybe I should just do something easier.”

But the mentorship provided by funding from a National Science Foundation Scholarship Program changed their mind. As a Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) Scholar at Kenyon, Naphtali’s education cost was covered without any loans or work-study obligations. Their first year started with a six-week summer program, followed by mentorship from professors and upper-class students, internships and other research opportunities. The goal, said STEM Scholarship grant author and Professor of Biology Karen Hicks, is to discover if such programs will help underrepresented students stick with their STEM majors and pursue successful careers.

Naphtali met weekly with student mentors who gave them advice on how to navigate the hardest classes. They formed study groups with other scholars in the STEM and KEEP (Kenyon Educational Enrichment Program) programs, and talked to professors they’d worked with in the summer program and in labs. All of this support helped them gain the confidence to pursue a biology major.

The challenges Naphtali faced are common for students from historically underrepresented minority groups around the country. Nationally, the majority of students who leave STEM do so within their first two years of college, according to the STEM Scholars grant application. And success in STEM is disproportionately tied to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status and family history of higher education, according to David Assai, senior director for science education at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

U.S. Department of Education data from 2003 to 2009 reveals that STEM students whose parents didn’t attend college are twice as likely as those whose parents have bachelor’s degrees to drop out of college. For Black, Latinx and Native American/Alaskan students, the disparity is even starker. In 2015, a third of first-year undergraduates interested in studying STEM were members of those underrepresented minority groups. But they make up just one-sixth percent of STEM graduates and a tenth of those who earned doctorates in those fields, according to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics.

Over the past five years, Kenyon has begun to take a hard look at the institutional cultures that foster such barriers and prevent historically underrepresented and underserved students from persisting in STEM fields. Faculty and administrators are changing how they teach, the colleagues they hire and promote, and their methods of evaluating students. President Sean Decatur, who is a biophysical chemist and the first Black president of the College, said there is good reason for this: “Science is a broader collective enterprise, not an individual one. The quality of science is significantly strengthened with a more diverse and inclusive group” working together to solve problems.

Professor of Chemistry John Hofferberth has studied equity in the sciences since 2013, when he was asked to apply for a grant funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. At the time, he thought the grant would fund research. Instead, HHMI asked colleges to change the learning environment and make their programs more inclusive to a diverse pool of STEM students. “That was not something I was qualified to do,” he said. “I was completely out of my comfort zone and expertise.”

He began to educate himself, reading and talking to colleagues about how to dismantle racism and build more inclusive classrooms. In 2017, Kenyon was one of 24 schools to win a five-year, $1 million HHMI grant. It funds programs that transform teaching methods, tenure and promotion criteria. Professors now are evaluated and promoted in part based on how inclusive they can make their classrooms. And that responsibility falls on everyone, regardless of their race or background. “Often (inclusivity) is work that is invisible and goes unrewarded,” Decatur said. “That invisible work can be especially burdensome for faculty of color.” Kenyon is trying to reduce that burden by teaching all faculty how to be more inclusive.

A key component is the Kenyon Equity Institute, a five-day intensive training course that teaches participants about systems of oppression and how to have important conversations about race and class. The course, taught by the Science Museum of Minnesota’s IDEAL Center, launched in August 2020 on Zoom.

After Hofferberth participated in the course, he started to see inequities that were embedded in the way he taught classes and interacted with students. “A lot of people think the air we breathe is just fine,” Hofferberth said. “I was one of those people.”

Hofferberth knows he’s the “stereotypically old science guy”: white, straight and affluent. “People have every reason to distrust my intentions and motivations,” he said. So he started holding “inclusion office hours,” buying snacks for students who showed up to talk with him on Friday afternoons. During these office hours, students are not allowed to discuss schoolwork, only issues related to inclusion in the sciences. His goal is to build trust so that students of color feel comfortable having honest conversations with him.

Hofferberth continues to build a more inclusive classroom. Since 2010, he has spent far less time lecturing and more time allowing students to apply what they’re learning in class. “It’s tough to make such a big change,” he said. “After a couple of years, I realized: this is way better.”

For Professor of Mathematics Carol Schumacher, one of her biggest challenges was learning how to keep some students from feeling excluded during group discussions. “It’s a lot harder than it looks to make this happen,” she admitted. “I’m feeling like a novice teacher in some ways.”

Schumacher has taught at Kenyon for 33 years and always been a proponent of inquiry-based learning. But after attending the Kenyon Equity Institute last year, she said she has learned “concrete strategies for helping everyone find their voice.”

For example, the institute spends a lot of time setting norms for group work so that bad patterns don’t have time to take hold. One rule is that you pass a talking stick to speak. Another is the ORID framework for group discussions: When students do a reading or encounter a new math problem, they’re taught to consider ideas that are objective (questions about facts), reflective (reactions and feelings), introspective (the implications) and decisional (what to do about it?).

It’s hard to guide students through all those steps, Schumacher said, especially when they’re accustomed to thinking professors only care about their final answer. But it is possible. That’s one of the most important things the equity institute taught her: “There exists a strategy for making this happen,” she said, and it’s “totally possible” to change the paradigm.

On the first day of classes last fall, Assistant Professor of Statistics Erin Leatherman reviewed the group norms with students, including one key point: Everyone has expertise to offer. “You have the right to ask for help,” she told her students, as well as the responsibility to give help. She then had students work in different groups every day, based on random criteria, and was amazed at the results. “I was just blown away by how these students were helping each other,” she said. One day, 22 out of 24 students spoke in class — an achievement that hadn’t happened until that semester.

She now gives “checkpoints” throughout the semester instead of exams. It’s the same test, worth 10 percent of their grade, but giving it a different name allows students to worry less about it. She’s also taken Hofferberth up on his offer to buy coffee for anyone who’s gone through the equity institute and wants to meet with their colleagues for follow-up conversations. Leatherman had coffee with more than half a dozen people from across the College, just to learn more about what they were doing and how they might work more together. The impact of this work has extended beyond the classroom for Leatherman. “My whole life has changed,” she said.

Decatur is proud of the way faculty members have embraced such pedagogical changes and incorporated inclusivity into their classrooms in countless ways. Assigning demographically mixed lab partners and asking students to do group work in class can go a long way toward helping students of color feel less isolated, he explained. “It’s not flashy,” he added, and “can be a pretty vulnerable self-examination” for professors. First, they must recognize: “Maybe the way I was teaching before was excluding people.”

Decatur remembers being the only Black student in his cohort when he was working toward a doctorate in chemistry in the 1990s. That feeling of isolation continued when he was a junior faculty member who was “regularly being mistaken for someone who must be a student.” He can empathize with students who would like to see more professors from diverse backgrounds.

There are faculty members of color in every department of the natural sciences, not just at the junior level but in the senior ranks, Decatur said. That’s quite an accomplishment at an institution with low faculty turnover. “We’re still not where our aspirations are,” Decatur said, but he’s proud of the progress that’s been made.

Professor of Chemistry Mo Hunsen grew up herding cattle in a small town outside Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. When he joined the Kenyon faculty in 2001, he remembered occasionally seeing one student of color on campus. In the fall of 2008, he had nearly 60 students in his organic chemistry class, and everyone appeared to be white. The following spring he was invited to speak to the Board of Trustees’ Diversity Committee, which held a panel discussion on the recruitment and retention of students of color in STEM fields. Hunsen explained that having one or two students of color on campus doesn’t help. Students need to form a cohort to thrive on campus.

Since then, he’s noticed a shift in the culture, and he attributes it to changes Kenyon has made, such as offering more financial aid packages and providing research opportunities to first- and second-year students. In his organic chemistry classes, Hunsen now sees a wide range of students, although the number who identify as racial and ethnic minorities is still rather low. “I feel for them,” Hunsen said of students from underrepresented groups. “If you don’t connect with them, you don’t understand.”

During the first two weeks of class, Hunsen requires students to come to his office so they can get to know each other. He tells them about his background, and they tell him where they come from and what they want to achieve. Those honest conversations lead to long-term mentorships, with students staying in touch years after graduation, and some finding jobs thanks to his guidance.

Hunsen said professors need to be more aware of the barriers students with lower incomes face in their quest to enter STEM fields. One student who was struggling in his class told him she couldn’t afford to take a summer course to raise her GPA. Others worry about taking out huge student loans to attend medical school.

Samantha Rojas ’12 put her dreams of becoming a doctor on hold after a rough second semester at Kenyon. A family tragedy distracted her from schoolwork, and her grades began to slip. As the daughter of Latino immigrants and the first in her family to attend college, she felt enormous pressure to succeed. “You can’t mess up,” she remembers thinking. “If you mess up, you go home.” She kept her concerns to herself, crying in her dorm restroom and confiding in a few close friends from the volleyball team. “I questioned whether or not I belonged at Kenyon constantly,” she said.

She didn’t graduate at the top of her class and didn’t know there were alternative paths to becoming a doctor. “Professor Hunsen always told me I was going to do great things, but I just couldn’t see that as I watched classmates gather letters of recommendation and apply to places like Harvard and Johns Hopkins,” she said. “I’m not smart enough to go to med school,” she thought.

After graduating in 2012, she became a research associate at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, and then a senior clinical research coordinator at the Ohio State University. There, she received more of the encouragement she had craved at Kenyon. “What are you doing here?” her boss asked her. “You should be in medical school.” She took his advice. Now, a decade after graduating college, she completed the highly selective MEDPATH program at Ohio State and now attends medical school there.

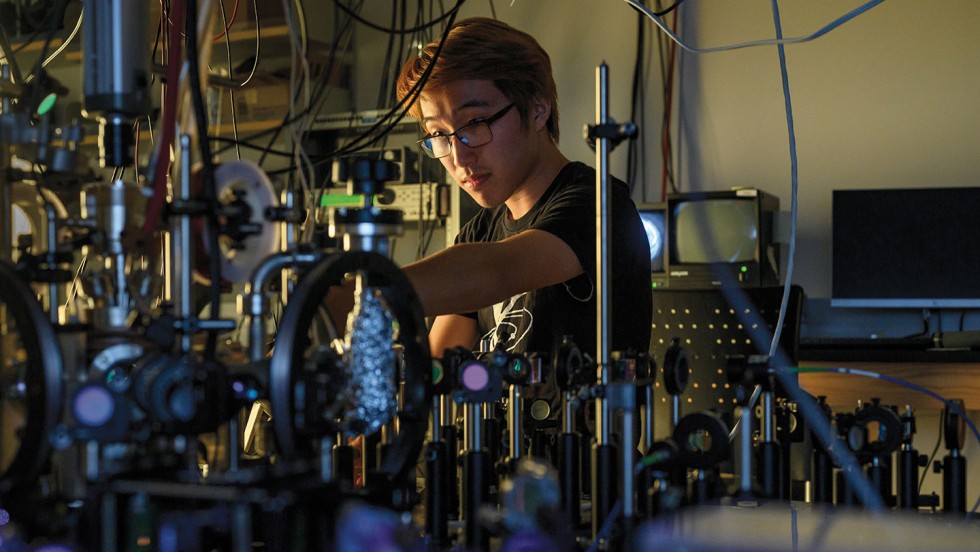

Phu Duong ’21 also wanted to be a doctor when he came to Kenyon as a STEM Scholar, but his grades were so low that he considered dropping out. As a Vietnamese student from Cleveland and the first member of his family to attend college in the U.S., he wasn’t sure how to turn things around. Then, during the second semester of his first year, he joined Professor of Biology Chris Gillen’s lab and, the following year, asked Gillen to work on a summer research project with him.

“Phu showed genuine interest in my research program, and when students do that I invite them to get involved regardless of the grades they are getting,” Gillen remembered. Sometimes students who are struggling in class, “are the very, very best research students,” he explained, because “the research setting differs from class and it can give students a sense of ownership and a different perspective toward their academic work.”

Gillen was right. Ten weeks in the lab studying yellow fever mosquitos changed Duong’s academic trajectory. “The stuff that I’m learning in the classroom can actually be applied to real-world problems,” Duong said he realized. “I felt like an adult, and the responsibility motivated me to do well.”

After his summer science research project, Duong shadowed a pediatric psychiatrist at the Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Molly Wimbiscus ’99, who attended Kenyon in the mid-1990s and now works with low-income children and refugees. One of her patients attended the same elementary school as Duong. This struck him as more than coincidence. “To me, it just seemed like the perfect career choice,” he said of Wimbiscus’ job. “I really could give back to my community if I just focused.”

He set an ultimatum for himself: He would earn a 4.0 during his last two years at Kenyon and take a heavy course load to raise his GPA a full point. And he did. He graduated magna cum laude in molecular biology, and now works as a research assistant at the Boron Lab at Case Western Reserve University Medical School.

Edna Kemboi ’16 experienced a different kind of culture shock when she moved to Gambier after attending a private all-girls school in Kenya. She emailed Hunsen and asked to work in his lab when she discovered he was Ethiopian. “I didn’t know there was a Black professor in the chemistry/biology department,” she said, much less someone who grew up just across the border from Kenya. She had noticed there were only one or two other Black students in her organic chemistry class, and didn’t feel comfortable asking other students if they could study together. “I needed someone that I could relate more to.”

Hunsen gave her a key to his lab so she could practice her skills at any time. “That made a connection for me and it did change my perception of research and science,” she said of the lab experience. “The freedom that I had in that lab opened internships and job opportunities for me. It made me who I am today – a curious scientist.” She now works as a GMP senior scientist at Andelyn Biosciences in Columbus, Ohio.

Programs like the Kenyon Equity Institute are designed to alleviate some of the most glaring inequities at Kenyon. But they can’t dismantle all the social and cultural barriers that linger on a campus that is predominantly white and affluent. To fill in the gaps, students have stepped up their own efforts to find and offer support for one another.

Ezra Moguel ’21 estimates there were three other people of color in his year in the physics department at Kenyon. Working as a teaching assistant for the KEEP and STEM Scholar programs, he noticed “a lot of people do come into Kenyon with this perceived barrier to entry for the sciences.”

That’s one reason he helped found chapters of the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanices and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) and Out in STEM (oStem) at Kenyon. At oSTEM, a nonprofit professional association for LGBTQ+ people in STEM, he helped push for gender-neutral bathrooms in the Science Quad. With SACNAS, he said it was comforting to get to know other people of color and hear their stories. “We’re not alone in this,” said Moguel, who identifies as transgender and queer, “even if you feel like you are sometimes.”

When Moguel, from Cleveland, was uncertain about his major, he spoke to Professor of Physics Tom Giblin, who encouraged him to take an introductory physics course. Giblin made it seem like anyone with an interest in the field should do that. “There was no barrier to entry to just trying out physics and seeing if I liked it,” Moguel said. He went on to major in physics and sociology, and spent three summers as a research assistant with the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, a group of scientists focused on the direct detection of gravitational waves. Giblin said his goal is simply to ensure no students leave physics because they feel excluded.

Georgia Stolle-McAllister ’20, another founding member of oSTEM, helped start the STEM Fair, a festival and cookout to help students across campus see what other science majors were doing and how fun the work could be. With oSTEM, the Baltimore native wanted to provide a social outlet and promote the visibility of LGBTQ+ people in sciences, “because you don’t necessarily see a lot of openly queer scientists, even though there are plenty.” She was part of the largest class of women the physics department ever produced. Since 2019, more than half the STEM graduates at Kenyon have been female, and this year their numbers reached 62 percent.

For Katya Naphtali, spending time with other STEM Scholars helps ease the feeling that they and other students from underrepresented backgrounds are invisible. “The level of wealth I saw at Kenyon was a lot more than I had ever seen before,” Naphtali said, adding that their classmates often assumed they grew up with the same advantages as their Kenyon peers.

A recently formed student club, First Generation Low Income (FIGLI), provides another kind of support. Members discuss issues such as the wealth gap on campus, particularly among roommates from vastly different backgrounds. They’ve also conducted Zoom meetings with professors who come from backgrounds similar to their own. It’s a powerful way to realize that socioeconomic status does not have to be a barrier to success. “It’s nice to see that there are professors at

Kenyon who had a similar experience and got through it and did well,” Naphtali said.

Why it matters: Since 1988, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute has invested millions of dollars in summer bridge programs and faculty mentoring for students from underrepresented minority groups. These programs helped a small number of talented students succeed but weren’t changing the overall persistence rates for minorities in STEM fields. “Here’s the problem: You can’t scale those (programs) to every student who would benefit,” said John Hofferberth, chemistry professor and director of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Inclusive Excellence program at Kenyon.

Instead, the institute decided to give grants to colleges that were willing to take a hard look at themselves — the way they teach, how they evaluate professors and how those professors evaluate students — to help “new majority” students succeed in the sciences. New majority students include: students from underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities, first-generation college students and working adults with families. Kenyon was one of 24 schools (and one of only two liberal arts colleges) to win a five-year, $1 million grant in 2017.

What it funds: Kenyon has used the grant to transform teaching methods, tenure and promotion criteria to make inclusive learning a priority. Some highlights of that work:

• Action groups, run by faculty, address topics such as student success and faculty belonging. Just before the pandemic hit, an action group on faculty belonging circulated guidelines for recruitment and retention of more professors from underrepresented minority groups. Assistant Biology Professor Arianna Smith, who chaired the group, said some of the key recommendations include: review job applications anonymously, provide candidates unique opportunities to diversify their teaching experience, and have candid conversations on the search committee about implicit bias.

• The Kenyon Equity Institute provides a five-day intensive training course about systems of oppression and ways to have difficult conversations about race and class. The course is open to faculty, staff and administrators across the College. This August marked the third year of the institute.

• Professors vie for course innovation grants, allowing them to change the way they teach the natural sciences.

A writer visits the site of Jubilee College in Peoria, Illinois, and finds the spirit of Kenyon’s founder is…

Read The StoryHow a marketer and trail-runner broke into an untapped market, scaled up and started over.

Read The Story