Building Community

A record-breaking gift helps Kenyon enrich its residential experience.

Read The StoryExplore new releases from members of the Kenyon community.

Though she normally splits her time between New York and the Netherlands, journalist and essayist Abigail Esman ’82 has spent much of the past year in New York City — the same place she spent months before the pandemic, working on her latest book, “Rage: Narcissism, Patriarchy, and the Culture of Terrorism” (Potomac Books/University of Nebraska Press).

In “Rage,” Esman uses her expertise to demonstrate how terrorists and domestic abusers often have personality traits in common, share related belief systems and have similar adverse childhood experiences.

New York City is also where the seeds of “Rage” were planted two decades ago.

“I was in New York on 9/11 and had recently gotten out of a relationship with an abusive partner,” Esman said. “In the days after the attack, I noticed everyone around the city was frightened, flinching at sudden sounds and movements. No one knew who was dangerous or when another attack would come. I realized everyone was responding to terrorism the same way I’d been responding to being in an abusive relationship.”

The threads between terrorism and domestic violence — the narcissism of the perpetrators, the response to shame with displays of power, the culture of honor, the misogyny and the dysfunctional family dynamics, just to name a few — began weaving together in Esman’s mind then and continued to do so the more she wrote and researched “Rage.” Drawing comparisons between O.J. Simpson, Osama Bin Laden, Dylann Roof and others, Esman demonstrates how a propensity toward narcissism leads to violence, and, when coupled with radicalization and opportunity, can result in death and destruction.

Though terrorism and radicalization are professional areas of expertise for Esman, “Rage” goes much deeper. While meticulously researched, the book reads like a memoir. Having survived two abusive relationships, she describes her own experiences of trauma intimately, lending insight that someone from the outside looking in wouldn’t be able to provide.

“Normally, when writing, I shut myself in and do little conversing or interacting with other people. I have to cut myself off and be in my own world. There were some chapters that wrote themselves and other chapters where I read journals and letters I’d kept from the time I was in those abusive relationships.”

One thing that can be especially challenging for abuse survivors to confront is how they came to accept “the new normal”— a point at which they don’t register the pain being inflicted on them and begin to think of the abuse they’re suffering as “just the way things are.” On a larger scale, Esman shows, that’s how the world responds to terrorism.

“I think it’s part of why President Trump got as far as he did,” Esman said. “He didn’t start out with an insurrection. If he had, people might have seen his insidious behavior for what it was.”

Both the normalization of violence that becomes domestic abuse and the radicalization toward terrorism often happen in private spheres — in the home or insular communities that uphold cultures of honor. But it is as true for entire cultures abroad — where honor killings take place and terrorist attacks are planned against westernized countries, as it is right here. In the U.S., where homegrown domestic terrorists, often motivated by the same sense of honor, carry out violence in the name of nativism and white supremacy. Since perpetrators of violence are produced in private spheres away from the public eye, it makes one wonder, how do you reach people in insular communities to make them understand that no sense of honor can legitimize violence?

“It can take generations, but I think change is happening now. It’s one of the effects of globalization and the internet: Middle Eastern women are getting access to new, Western ideas. Although sometimes the internet can also be dangerous for women.” Esman paused, recalling the online ISIS recruiters she details in “Rage,” who lure girls and women into lives as jihadist wives, subject to untold acts of domestic violence before being made to support acts of terrorism. “But these women are gaining rights a little at a time, and it’s making a difference. That’s why we need to support these women, do outreach, support nongovernmental organizations that work with women and prioritize human rights.”

According to Esman, prioritizing women’s rights isn’t vital only for countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia, but for the U.S. as well.

“When I was a girl and we were taught sex-ed in school, the girls were taken to a different room to learn how to put a sanitary napkin on a teddy bear. Nowhere did we hear that it’s not okay for a boy to treat you in this way, that they shouldn’t hit you,” she said.

As important as it is for children to be taught how to identify these patterns of behavior so they don’t come to think abuse is normal, it’s equally important to teach children alternatives to violence, she explained.

Despite the challenges and against the odds, rehabilitation for terrorists and domestic abusers is possible. Esman sat down with reformed terrorists and a reformed white supremacist to discuss what led to the change in their belief systems. For Jason Walters, one former terrorist Esman spoke to, watching “Schindler’s List” in prison shifted his entire mindset. And that, she said, can be key. “Arts education is a phenomenal tool. Reading books and making art creates a capacity for abstraction, and abstract thinking is necessary for empathy. That’s something I’ve always believed — since my Kenyon years.”

Even after researching and writing about the myriad horrors documented in “Rage,” Esman remains hopeful. “We’re heading in the right direction,” she said. “I’m optimistic that the more we learn and understand, the more we can heal.”

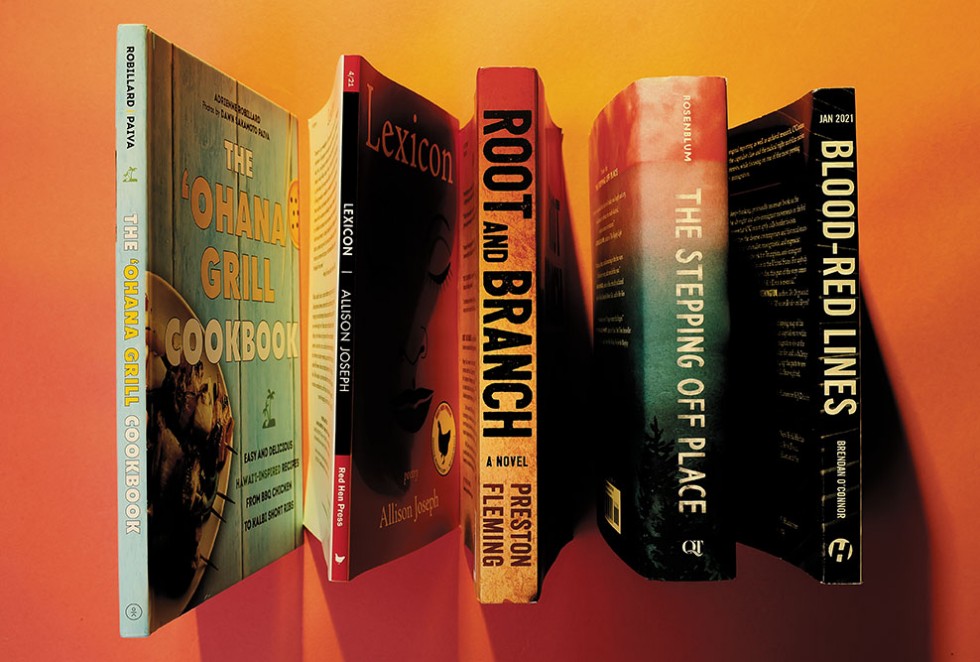

By Adrienne Robillard and Dawn Sakamoto Paiva ’99

Bring the diverse flavors and cultures of the Pacific to your own backyard with this cookbook. Featuring Sakamoto Paiva’s photos throughout, “The ‘Ohana Grill Cookbook” has recipes for carnivores and vegetarians alike, and just in time for warmer weather. (Ulysses Press)

By Allison Joseph ’88

In her 12th book of poetry, Joseph has made “Lexicon” her love letter to language. The poems play with form in unexpected, imaginative ways as she grieves the loss of a parent, celebrates Black love and navigates the dual danger zones of racism and sexism. The poems are meditations on Joseph’s love of words and the poetic form, though as a Black woman, they don’t always love her back. (Red Hen Press)

By Cameron Kelly Rosenblum ’89

Debut author Rosenblum’s young adult novel is a page-turner that’s a testament to the prevailing stigma of mental illness — there is no “right” way to grieve and humans, even those you think you know best, contain multitudes. The novel will keep you up past your bedtime, alternating between laughter and reaching for the tissue box. (Quill Tree Books/HarperCollins Publishers)

By Brendan O'Connor ’12

Journalist O’Connor examines border fascism — the anti-immigrant movements led by white nationalists. Bringing generations of eugenicist, xenophobic, misogynistic and racist beliefs to light, O’Connor lays the framework for explaining Trump’s rise to power and heightened violence against immigrants. (Haymarket Books)

By Preston Fleming ’71

Complete with masterful political intrigue, high-stakes security threats and hefty ethical implications, this realistic thriller is as timely as it is frighteningly entertaining. Fleming’s seventh novel explores human rights from inside the government and asks just how far the government should go in the name of security. (PF Publishing)

A record-breaking gift helps Kenyon enrich its residential experience.

Read The StoryBryan Doerries found comfort in the ancient Greek tragedies he studied in college. Here’s how he has helped thousands…

Read The Story16 reasons Kenyon alumni are optimistic about the future.

Read The Story