Darci Does It

A fiber artist uses her platform to challenge perceptions of the knitting community.

Read The StoryJamal Jordan ’12 takes readers on a moving journey in his debut book.

From big cities known for being queer friendly, like San Francisco, to regions and countries not thought of as being supportive of queer people, like the American South and South Africa, Jamal Jordan ’12 takes readers on a journey through moving portraits, aww-inspiring meet-cutes, and heartwarming tales of thriving queer couples of color in “Queer Love in Color.” His debut book, published in May by Ten Speed Press (an imprint of Random House), is a loving portrayal of 45 queer couples and families of color around the world.

For Jordan, a queer Black man who grew up in both Mobile, Alabama, and Detroit, the book is a deeply personal project.

“It felt important for me to frame the book as a gift to my younger self, to find and make these images in places where I wouldn’t have thought they existed when I was growing up,” Jordan said.

Having lived in the South, Jordan knew there was so much more to the stories of LGBTQ+ people of color there than brushes with homophobia.

“I needed to rediscover places where I spent time as a child and learn that there were communities around that I just didn’t have access to when I was younger,” Jordan said. “Growing up queer in the South can be a lonely experience. It felt nice to see that there were queer communities of color that have always existed there.”

Though representation of queer people of color in media is increasing as time passes, there are still many stories that hinge upon experiences of tragedy. This can lead people to believe that it’s difficult, if not impossible, for queer people of color to be happy and thriving. “Queer Love in Color” is Jordan’s way of combating these stereotypes.

“It comes from this very basic desire to be seen and know that love is possible for you. It struck me just how common of a thread that was in queer communities of color, and that made me want to go on this mission to make this book,” Jordan said.

The seed for “Queer Love in Color” was planted when Jordan was working as a visual editor at The New York Times. The publication was curating a Pride section, and Jordan pitched his editor the premise: stories and portraits of queer people of color throughout the country.

“I didn’t realize the impact it would have. I remember when I tweeted it someone DM’d me and said, ‘Jamal, your tweet is currently the largest external traffic driver to The New York Times website,’” Jordan said.

The outpouring of interest in his photos and stories made Jordan see just how needed a project like this was.

“So much of the feedback I got was, ‘Thank you. I never thought I’d see an old lesbian Black couple just casually in The New York Times in a story that’s not framed around tragedy.’ That felt really rewarding,” Jordan shared.

The stereotypes around tragedy aren’t just perpetuated by people outside the queer community — they exist within it, too, especially when it comes to where queer people of color grew up or choose to live as adults. It is often assumed that regions like the American South and countries like South Africa cannot possibly allow queer people of color to find love and happiness, when in reality that couldn’t be further from the truth.

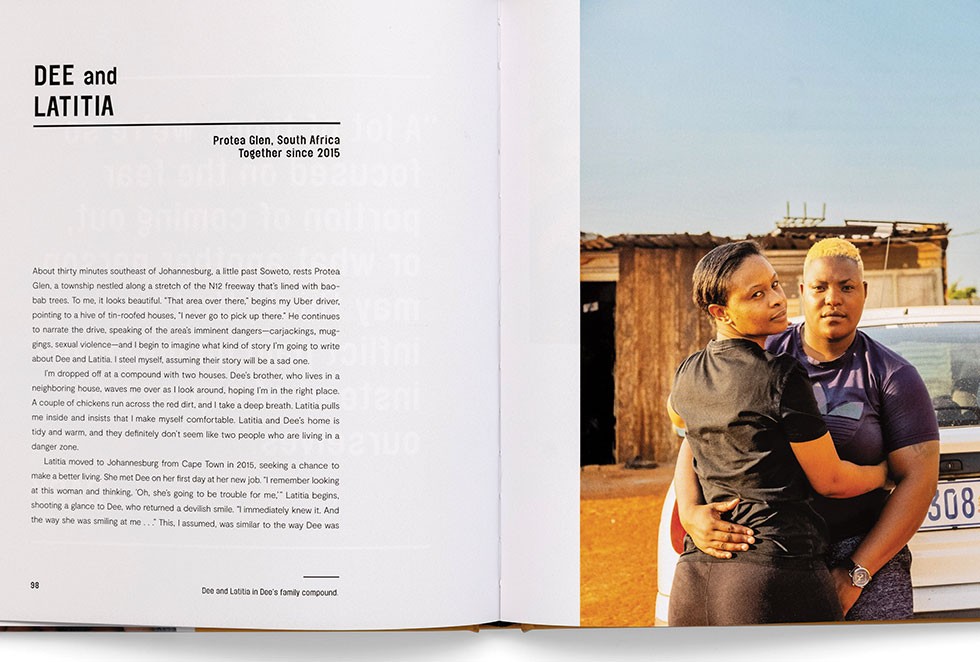

The story of Dee and Latitia, a lesbian couple who live in Soweto, outside of Johannesburg, is one example of that.

“Nearly every bit of Western media has told me that their lives cannot have any dynamism or dimension. It was jarring to realize that I had my own prejudices against the community that I needed to work through,” Jordan said of having his assumptions challenged. “It also gave me hope that even in spaces that are portrayed as being really awful for queer people, that queer people are still finding joy and still pushing back against that narrative so powerfully.”

Another example is Willie and Curtis, a Black couple in their 70s. Jordan commented that growing up as a gay Black man in the South must have been torturous but they quickly put that notion to bed, citing the closeness of queer communities in the South. Jordan got to experience the strengths of the South’s queer communities himself on his travels.

Conversations with Dee and Latitia, and Willie and Curtis, sent Jordan into deep periods of reflection.

“I knew the project would only work if it was honest. I wanted to talk about the times when a perception was challenged or when the whole narrative changes right in front of your eyes,” Jordan shared.

He frequently thinks about a lesbian couple he met in Chicago, Amisha and Neena. They met in Chicago when one partner was still married to a man, and they had a 13-year friendship that turned into a courtship that both never thought would happen. One day both simultaneously realized they should take a chance to be together.

“They were thinking, ‘What if this magic moment passes us and we don’t ever have that moment again for the rest of our lives?’ And now they have this beautiful, strong bond that I think will last forever. I left their interview thinking we have these moments of magic that come to us every day and if we don’t lean into those then who knows how much worse our lives would be,” said Jordan. “I still can’t read their story without tearing up a bit. They taught me so much about persistence, resilience and leaning into chance.”

Another family — El-Farouk and Troy with their kid Tajalli — was especially moving for Jordan. He met them in Toronto and was in a writer’s funk at the time, wondering where the book was going.

“They talked about how as queer men of color and refugees that their entire lives they’ve been taught to dislike things about themselves. The key to their love, they told me, was this unlearning process — this unlearning and relearning of the self that so many queer people of color around the world have to do,” Jordan explained. “After them, I started talking to other couples about that same experience and realized that’s what this book is about.”

Jordan is no stranger to this process of unlearning and relearning. “I remember being a sophomore at Kenyon and not getting into this creative nonfiction class. I remember the small chip on my shoulder forming then and thinking, ‘I’ll show you guys!’” Jordan said, recalling that painful moment. “A lot of growth has happened in the world over the past decade and the College is probably more amenable now to less tradi-tional forms of storytelling and writers of different viewpoints, but it was hard for me to deal with as a 19-year-old. It was jarring being this poor Black kid from Detroit suddenly at Kenyon. I had to graduate college with a very sure sense of the question, ‘Am I a good writer?’”

Though the answer is undoubtedly yes, it wouldn’t be the last time Jordan’s talent would be dismissed. Editors at VICE and NBC tried to discourage him from journalism.

“I’ll never forget this day at NBC. It was the day Matt Lauer got fired, the day of the Rockefeller [Christmas] tree lighting, and the day I had my interview at The New York Times. I sneak out of the office for two hours, go to the Times, and have this great interview. I get back to 30 Rock and my boss calls me into her office. She’s got this very concerned tone and basically says, ‘Your work is cool and all but I don’t see you working out in mainstream journalism. Sorry, I’m just trying to help you not waste your time.’ I just remember laughing.”

It worked out for the best because Jordan got the job at The New York Times, where “Queer Love in Color” took shape, and where he was able to take six and a half months of book leave to complete his manuscript.

“Someone will blatantly tell you that you can’t do something and it’s obviously wrong,” Jordan said.

A fiber artist uses her platform to challenge perceptions of the knitting community.

Read The StoryEleanor Tetreault ‘21 shares her experience as lead author of an attention-grabbing psychological study.

Read The StoryAs Kenyon’s Gund Gallery celebrates its first 10 years, we look back at its influential works and programming…

Read The Story