Cleared for Liftoff

Behind the music with Nick Petricca '09 of the popular rock band Walk the Moon, which got its start at Kenyon.

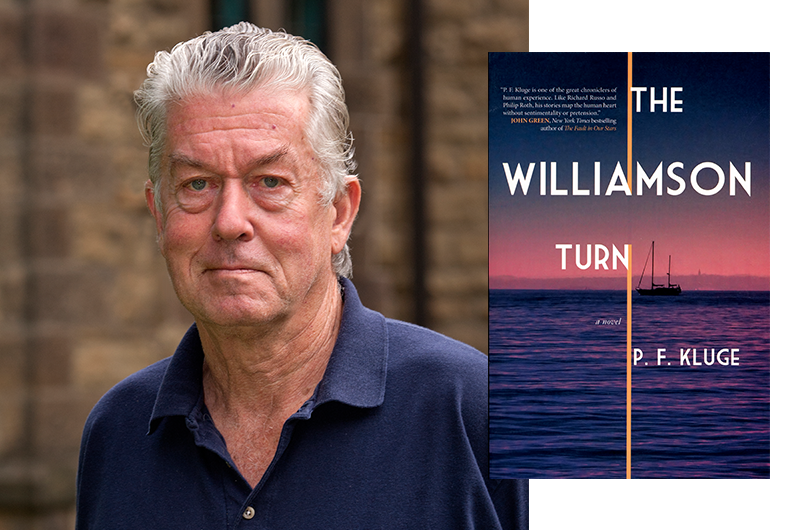

Read The StoryA new novel by P.F. Kluge '64 presents a fictionalized account of a semester-long voyage, reflecting poignantly on the experience of world travel.

As a student intern at the Kenyon Review, I would walk daily past the office of Writer-in-Residence P.F. Kluge ’64, offering a few words of greeting as he clacked away at his typewriter. One day, a sticky note appeared on his closed office door: “Out of town, out of country,” it read, with a jaunty doodle of a ship. Little did I know that, in the spring of 2011, Kluge was circumnavigating the globe as an instructor on the “Semester at Sea” program, gathering material for his 12th book.

Kluge’s new novel, “The Williamson Turn,” presents a fictionalized account of one such semester-long voyage, reflecting poignantly, though never nostalgically, on the experience of world travel. Following three central characters — a writer, a professor and an administrator — Kluge juxtaposes the experiences of various voyagers in order to consider such weighty subjects as the value of travel, the notion of global citizenship, aging and death, and the uncertainty of the future.

The novel’s opening scene offers a sly wink to any who have known Kluge in person. Will Post, a notable New Jersey author who teaches travel writing on the university ship, opens the novel hunting for a spot on the ship to enjoy a cigar — a pastime that students and faculty at Kenyon may grinningly associate with Kluge himself, often found puffing a hefty robusto in an Adirondack chair outside Finn House.

Such obvious resonances between Kluge and Post remind readers that “The Williamson Turn” is itself a piece of travel writing, culled from experience as well as imagination (as Kluge notes in the afterword). Post’s outspoken disdain for authority quickly marks him as one of the ship’s outsiders: “Do something a little different on a ship,” Kluge writes, “and you acquire a label.” Post — dubbed “the cigar man”— is afforded by his outsider status the privileges of a detached observer, relaying with anthropological scrutiny the reactions of his fellow voyagers to the vast experiment that is Semester at Sea.

Post’s disaffected, though not quite cynical, manner, allows him to dissect the experience of global travel without preciousness. “On a voyage that took itself so seriously,” Kluge writes of Post, “he felt at ease among [the] irreverent minority.” Post shakes his head at camera-clutching straight-A students who scour Manaus for the authentically primitive, or the Taj Mahal for a glimpse of the “real” India. Instead, Post praises those whose clandestine adventures afford them a taste of real experience and cultural insight. Flicking through writing assignments, Post maps students’ various attempts to make sense of the voyage, ranging from trite cliché to insightful irony to thoughtful introspection. He becomes our guide, always ready to explode the glamour of “tourist traps” and suggest more meaningful engagements with the world.

In addition to Post, the novel follows the voyages of Harold Beckmann, an aging professor, and Leo Underwood, the ship’s egotistical executive dean. Like Post, these male leads seem a bit surly from the outset. But the deftness of Kluge’s craft lies in his ability to render such characters with remarkable complexity: A bit at a time, we glimpse the softness behind tough exteriors, especially as their paths intersect with those of female passengers. And while the novel may feature a few too many cringeworthy erotic encounters between female students and male faculty, its cast of characters is not without a handful of strong and compelling women.

“The Williamson Turn” is a delightful romp, full of vibrant personalities and witty one-liners — “let them eat hake,” scoffs Post in response to the passengers who fail to appreciate the splendor of a Brazilian fish market. It also invites stimulating reflection, as when Beckmann asks his students whether the relationship between colonizer and colonized is inevitably sexual. At its best, however, “The Williamson Turn” takes unfamiliar settings as an opportunity to meditate on the deepest recesses of the human mind. “When you’re on a three-and-a-half-month voyage,” quips Post, “you ought to be able to sit and consider the sea.”

Kluge does just that, and powerfully. When Post explains that the turn which comprises the novel’s title is a maneuver employed to find a body that has gone overboard, Beckmann posits that everyone, at some point, has considered what it would be like to jump.

“That’s why they have the Williamson Turn,” Post replies.

Review by Fred Baumann, professor of political science

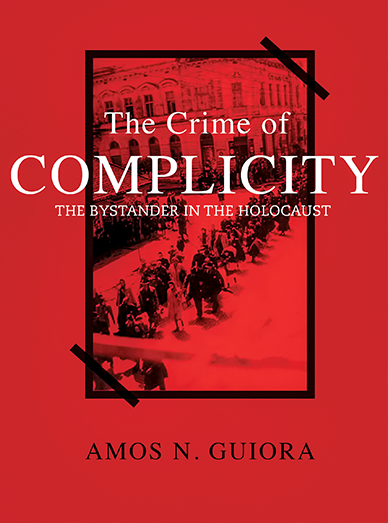

Amos Guiora ’79 leads an interesting life. A law professor at the University of Utah, and formerly a lieutenant colonel in the Israeli Defense Forces Judge Advocate General Corps, he is one of the world’s leading authorities in counterterrorism law. Guiora frequently appears in big media and regularly speaks at Kenyon (where he has also occasionally taught). Moreover, he is a widely published scholar.

His latest book, “The Crime of Complicity: The Bystander in the Holocaust” (Ankerwycke, an imprint of the American Bar Association), stands apart from his others in that it is personal, involving the deeply painful memories of what happened to his family in the Holocaust. Ever the lawyer, he uses this personal material to make a case that we can learn a lesson from those very different times. Guiora holds the bystander as culpable and legally punishable. He sets the bar low: Bystanders have to call for help, not necessarily risk their lives getting physically involved. And he limits the legal responsibility to the bystander who is physically present, not requiring action based on moral beliefs.

The book mingles memoir, history and legal/moral argument. At first , this seemed off-putting, but then I understood it to be a reflection of Guiora’s own thinking and feeling as he wrote. As such, I think it works well. He compares the situation of Jews and those who stood by in Holland, Germany and Hungary. As always in such books, some of the incidents are horrifying, like the father who sacrificed his daughter so that he would keep ownership of the family house after the war, and Guiora probes with great sympathy and understanding the outlooks even of those he condemns most strongly.

It’s a fair-minded book and one that is painfully honest about the author as well. What comes through most strongly is the abandonment of the Jews, who, whether assimilated as in Holland or a separate people as in Hungary, knew they could count on no one. The image of the Death March, where some just turned away, others looked on blankly, while others taunted and cursed the victims, pervades.

Linking the Holocaust memoir with the case for a bystander law in the United States is problematic. A Nazi law punishing bystanders would have actually worked against the victims: The guilty “bystander” would have been someone who just watched while others helped Jews instead of reporting the Jews to the authorities. And the risk to the person who did help the Jews would have been far, far greater then than now.

Still, the extreme contemporary examples that Guiora cites powerfully make the case for the need for such a law today. The Vanderbilt football player who did nothing to keep his roommate from raping a woman and went scot-free makes the moral point Guiora wants to turn into a legal one.

But that case, however morally compelling, has its own difficulties when faced with this country’s principles and basic understanding of the purpose of law. To his great credit, Guiora gives a lot of space and weight to the counterarguments. He admits that such a law would put interveners at risk, and may do harm; that the intervener may misread the situation and, say, take the victim for the aggressor; and, above all, that a law of this sort asks our legal system to legislate moral behavior and not just protect rights.

Yet this is where the Holocaust memories tell most strongly, in that they allow for a moral reflection on the extreme case. By being shown the picture as vividly as possible, the reader comes to see what is really at stake.

It seems to me that Guiora’s case is worth serious consideration. Yes, our Lockean form of government is about rights and not virtue. But Locke, in chapter two of the “The Second Treatise on Civil Government,” speaks of an obligation under natural law to help others, “where his own preservation comes not in competition.” And while the case that worries me most is that of the bystander who has no time to call authorities, intervenes, and finds him or herself defending a lawsuit, I do think that the range of possibilities within liberal democracy allow for the legislation of morality to a limited extent. That might well include this law, though only for clearly defined and obvious cases.

William Aulenbach ’54, “Cramming for the Finals”

(Summit Run Press). A retired Episcopal clergyman, Aulenbach recounts his own faith journey and provocatively questions traditional ideas.

Jennifer Carter ’93, “Aced” and “Spiked”

(Psyched Publishing). Carter is a noted psychologist who specializes in sports psychology and eating disorders — but, under her pen name, Jennifer Lane, she also churns out compelling young-adult romances. These two complete her “college volleyball series.”

Jesse Donaldson ’02, “On Homesickness: A Plea”

(West Virginia University Press). In short, intensely lyrical passages, one for each of Kentucky’s counties, Donaldson meditates on history, home and belonging. That these small, memoir-like prose-poems speak lovingly to his wife and take the two of them toward the birth of their baby deepens their resonance.

Daniel Mark Epstein ’70, “The Loyal Son: The War in Ben Franklin’s House”

(Ballantine). The prolific biographer and poet here tells the remarkable story of founding father Ben Franklin and his illegitimate son, William, whom Franklin would raise as his own — but who would become a Loyalist during the Revolution.

John Green ’00, “Turtles All the Way Down”

(Dutton Books for Young Readers). Green’s first book since the best-selling “The Fault in Our Stars” (2012) centers on 16-year-old Aza Holmes, a high school student living with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and her search for a fugitive billionaire. More information on the book will appear in a future Bulletin.

Web extra: Yasmin Nesbat '18 set out to discover the meaning behind Green's newest title.

Ariel Helfer ’08, “Socrates and Alcibiades: Plato’s Drama of Political Ambition and Philosophy”

(University of Pennsylvania Press). In exploring Plato’s portrayals of the controversial Athenian statesman Alcibiades, Helfer takes up the larger question of the tension between altruism and ego in political ambition.

Scott Jarrett ’92, “Traffick-wocky: Austin Traffic Poetry & Whatnot.”

Writing as Tex Mopac, the “Bard of Austin Traffic,” Jarrett renders the commuter’s frustration into sheer fun.

Sheppard Benet Kominars ’53, “Angles of Incidence: Poems of 7 Decades.”

“I am an antique fly on the wall / of a lifetime,” writes Kominars, who evokes both age and youth in these poems, a few of which date from his Kenyon student days.

Fred McGavran ’65, “Recycled Glass and Other Stories”

(Glass Lyre Press). A wealthy American tourist dies in India and finds himself reincarnated as a water buffalo driver on a mission. Recycled-glass countertops in which human body parts are preserved present a business opportunity. McGavran’s new stories consistently surprise us with macabre ironies.

Zachary Nowak ’99, editor, with co-editors Peter Naccarato and Elgin K. Eckert, “Representing Italy Through Food”

(Bloomsbury). The scholarly essays in this book take up topics ranging from the slow food movement, to food in police fiction, to images of Italian cuisine around the world, to marketing (including a paper called “Semiotics of sauce: representing Italian/American identity through pasta sauces”).

Behind the music with Nick Petricca '09 of the popular rock band Walk the Moon, which got its start at Kenyon.

Read The StoryAt Kenyon, student activists tackle national and international issues — as well as concerns closer to campus…

Read The StoryFrom pilgrimage souvenirs to rubber ducks, peek inside the personal collections of Kenyon alumni and faculty.

Read The Story