Object Permanence

From pilgrimage souvenirs to rubber ducks, peek inside the personal collections of Kenyon alumni and faculty.

Read The StoryA Q&A with librarian Elizabeth Williams-Clymer.

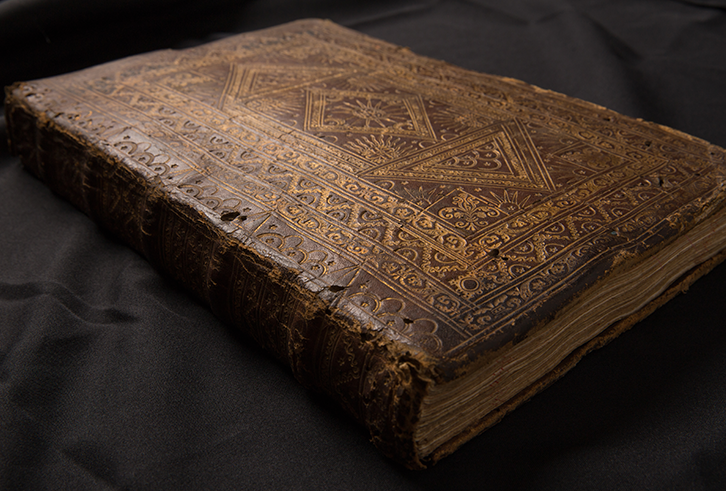

Image: Petition to King Philip of Spain, circa 1611 to 1632.

Hand-written, unpublished poems by W.B. Yeats, medieval illuminated manuscripts, a two-volume first edition of “Lolita.” These are just a few of the gems that can be found in the Greenslade Special Collections and Archives, which is full of significant primary sources that are rare, valuable or fragile. In the digital age, when information is ubiquitous, these precious objects have started to play a more important role at colleges: The opportunity to work in-person with such materials is a draw for both students and faculty. We asked Special Collections Librarian Elizabeth Williams-Clymer to take us on a brief tour of the cache.

What’s happening in Special Collections’ exhibitions?

Right now we have an exhibition called “Kenyon Away, Kenyon at Home,” about Kenyon’s ties abroad. It’s focused on three people. First, there’s our second president, Charles Pettit McIlvaine, who was sent to England during the Civil War to convince England to not support the South. Second, there’s Olof Palme, an alum who became the prime minister of Sweden and was assassinated in the ’80s. The third person is Junzō Shōno, who spent a year at Kenyon. In the ’60s, he wrote a book about his time in Gambier, “Sojourn in Gambier,” which became somewhat popular in his native Japan. It’s amazing to see what Kenyon folks have done, worldwide.

What’s your favorite object in the collection, if you had to pick just one?

We have a hand-painted, exceptionally bound manuscript from Spain, circa 1611 to 1632. The cover is leather with gold leaf, and the pages are vellum. It’s a petition to King Philip, detailing the rights and privileges of a noble family, the Campuzanos, and it’s signed by the king. It must have been a very important, valuable book, which the author was commissioned to create — because the printing press had already been invented. Assistant Professor of English Piers Brown uses this book for his class, “The History of the Book,” in which each student “adopts” a book to study for the semester. Of course, there’s always demand for this book.

What are the collection’s “greatest hits” — i.e., materials that classes use most frequently?

Two spring to mind: a collection of prints by George Catlin, from the 1840s, that are part of the Eugene F. Bigler Collection of Art & Archaeology (Bigler was Class of 1900). Catlin was the first artist to depict the Plains Indians in their native territories. His paintings were often the first glimpse of Native Americans that Europeans had ever seen.

Also, the “Nuremburg Chronicle,” a book printed in that city in 1493, about the history of the world. A gift from the Class of 1955, it was one of the first early printed books to successfully integrate illustrations along with text. It’s used by classes in history, art history (it includes beautiful wood-block printing) and religious studies. Of course, it doesn’t cover the discovery of America by Europeans. I think it’s just fascinating to think about a time when this country wasn’t even on the radar!

From pilgrimage souvenirs to rubber ducks, peek inside the personal collections of Kenyon alumni and faculty.

Read The StoryAt Kenyon, student activists tackle national and international issues — as well as concerns closer to campus…

Read The StoryBehind the music with Nick Petricca '09 of the popular rock band Walk the Moon, which got its start at Kenyon.

Read The Story