The Cheerful Critic

How Margaret Willison '07 turned her love of pop culture into a mini media empire.

Read The StoryFrom doughnuts to e-cigarettes, Kenyon students use science to educate middle schoolers on addiction.

Story by Mary Keister | Photos by Cameron Peters ’20

Imagine you're biting into a warm doughnut, sinking your teeth into the soft crust and licking powdered sugar off your lips. As the sugar hits your tongue, it blasts your taste buds and signals your brain to enter a state of saccharine bliss. But as we devour doughnuts, or any other sugary treat, how does our brain know to respond by delivering the sensation of sweetness?

Associate Professor of Chemistry Sheryl Hemkin holds the answer. So do her students. And now, thanks to work Hemkin's students did in an upper-level CHEM 401 seminar last fall, sixth-grade students at a nearby school know the answer as well.

The work by Hemkin and her class was part of a larger initiative in conjunction with the Knox County Health Department and St. Vincent de Paul School, a Catholic school based in Mount Vernon, Ohio, to create interactive educational modules showing the effects that various substances, such as alcohol, nicotine, sugar and caffeine, can have on someone's body. Ultimately, they hoped to create a program incorporating videos, age-appropriate readings and hands-on activities that could supplement health curricula and demonstrate what happens on a molecular level when someone drinks a beer, smokes hookah or tries an e-cigarette.

"Everything you consume contains chemicals, with each chemical having a particular shape," Hemkin said, "and it interacts with the body in a different way because of that molecular shape."

Over the course of the semester, Hemkin's students and the sixth-graders met both at St. Vincent's and in Kenyon's labs to discuss the chemistry behind a variety of substances — including doughnuts. But the chemistry class wanted to pay particularly close attention to the substances most commonly used among the pre-teens and their peers: alcohol and nicotine. And in a county, and a state, hit hard by an opioid epidemic, Hemkin and her students kept their eyes on a higher goal: convincing the middle-school students to think about the science of whatever they consume, throughout their lives, so they would make healthy choices long after graduating the middle schools and high schools of Knox County.

In Knox County schools in 2011, the Knox Substance Abuse Action Team (KSAAT) began conducting the Pride Survey, a questionnaire widely used across the country to gauge substance abuse among teenagers. As the results of each biennial survey were returned, KSAAT members noticed a worrying trend: Usage of cigarettes and alcohol was increasing among Knox County youth, and teenagers’ perception of the harmful effects of these substances was decreasing. In 2015, 2.9 percent of sixth-graders surveyed reported trying cigarettes in the month prior to the survey, and 6 percent reported alcohol consumption that month. Among eighth-grade students surveyed in 2015 about their previous month’s use of substances, 7.6 percent reported trying cigarettes, and 7.4 percent reported alcohol consumption. In the Pride Survey conducted in 2011, 1.2 percent of sixth-graders reported trying cigarettes in the previous month, and 2.1 percent reported alcohol consumption.

With support from a federal Drug-Free Communities grant, KSAAT coordinator Ashley Phillips began exploring ways to better educate Knox County youth about substance abuse. She conducted focus groups and heard from teenagers that they weren’t opposed to more education about substance abuse — they just wanted it to be higher-level than any facts they could Google on their own.

Phillips shared feedback from her focus groups with Jen Odenweller, then-director of Kenyon’s Office for Community Partnerships, who volunteers with KSAAT’s youth committee, and in the fall of 2016, the pair met with Hemkin to discuss the possibility of a Kenyon-led project addressing substance abuse among Knox County teenagers. Together, they decided to focus their initial efforts on a pilot program among sixth-graders at St. Vincent de Paul School, whose principal also is involved with KSAAT.

“Our Pride Survey tells us that the average age that a child takes their first drink or starts using [drugs and cigarettes] is 12,” Phillips said. “So if we’re going to prevent this from happening, we need to really focus on those children age 12 and even younger. ... They’re going into middle school — that’s when they’re open to new experiences. Their relationship with their parents might start to seem a little bit awkward, and that’s kind of when the water starts to part. So this was a prime opportunity.”

Hemkin had been considering how she could use her expertise as a chemist as a force for good in a community aching under the weight of an opioid crisis. This partnership provided her with an open door to not only help her community become healthier, but also to promote science education in a meaningful way.

She decided to collaborate with Sharon Tharp, the sixth-grade science teacher at St. Vincent’s, to create an educational program that could eventually be scaled to different grade levels and deployed at schools across the county. Students in Hemkin’s class would develop hands-on activities outlining facts of different molecules — primarily ethanol and nicotine molecules — as well as the effects they inflict on the body. Hemkin’s students also would design five-minute videos to reinforce the classroom activities, with support from an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant facilitated through the Center for Innovative Pedagogy.

To test-drive their methods of teaching sixth-graders about various molecules, Hemkin’s students started small, focusing on one molecule: sucrose, or sugar. They gave short presentations in Tharp’s class to practice explaining how brains react to sugar — that molecule receptors on your tongue are like baseball mitts, and sucrose molecules are like baseballs that are easily nestled into those taste bud receptors.

“It’s really easy to catch the baseball in the baseball mitt, but if you throw a Frisbee or a football, it can’t be caught,” Hemkin explained. “You could imagine that’s like a molecule responsible for bitter taste, or gluten, or other molecules that aren’t sugars, that come with all the foods and other substances you put in your mouth.”

Metaphors proved key to the work of the Kenyon students, who puzzled over how to best connect with middle-school students with varying levels of science knowledge. Because their educational modules would be supplemental to existing middle school health curricula, members of Hemkin’s class wanted to ensure that their lessons would be engaging and easy to digest.

“We definitely work in analogies a lot,” said Jenna Bouquot ’19, a chemistry major from Hudson, Ohio. “When you’re in the sciences, you spend a lot of time working on learning how to talk to other people who do science, and you learn all the technical terms. It is a completely different challenge to explain these really difficult scientific concepts to people who have no science background.”

While workshopping video ideas in Hemkin’s class, her students transformed the idea of a sip of beer into an image of a water balloon splattering inside someone’s body, releasing simplistic, water-soluble ethanol molecules (C2H6O) into the bloodstream and organs. The tiny molecules could easily flow through membranes in the body and attach to a variety of receptors, quickly causing a tipsy sensation, the students explained.

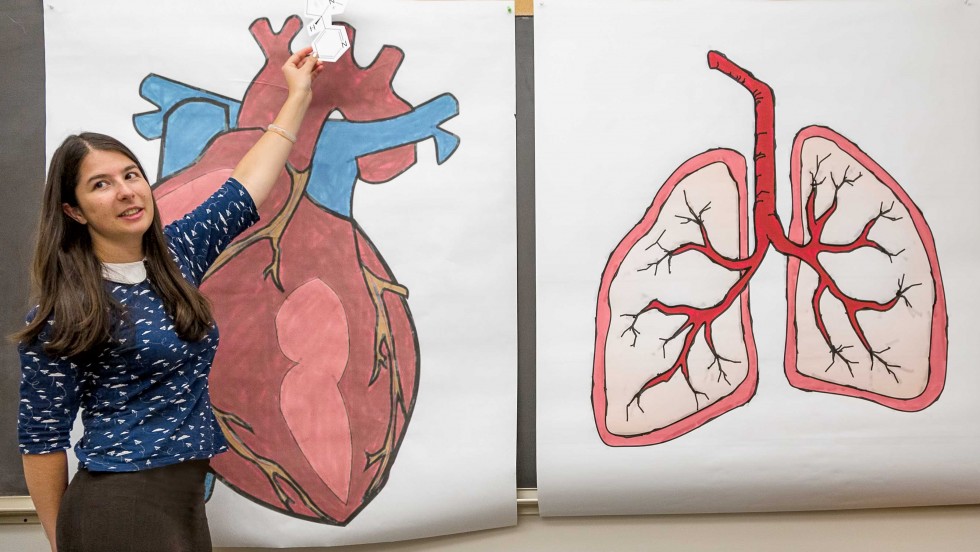

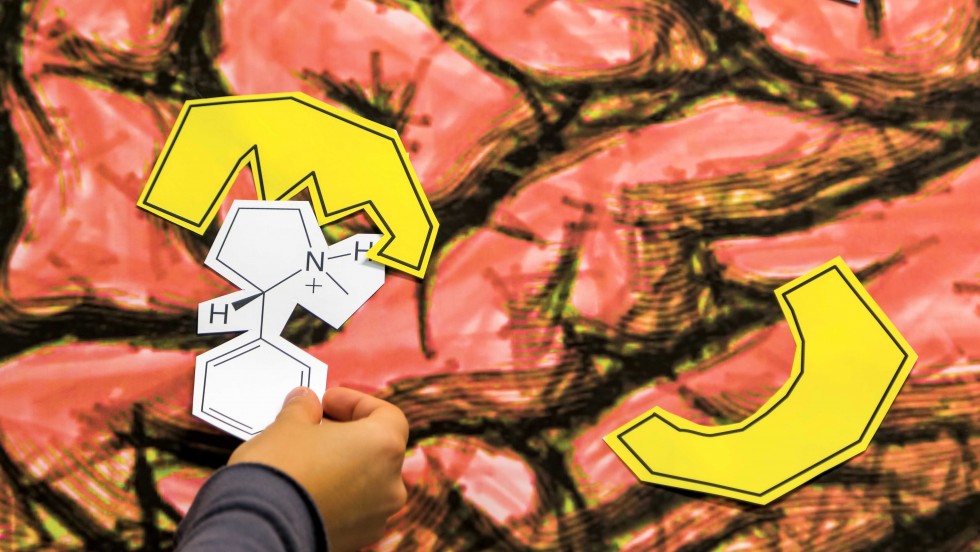

Nicotine was depicted as a clunky molecule, knocking throughout the body in search of the few receptors to which it could attach its complex chemical scaffolding. On its way to those select receptors in the brain, the students explained, the nicotine molecule — C10H14N2 — could damage lungs, the heart and anything else in its path.

Hemkin’s class spent considerable time learning the details of each molecule they planned to feature in their in-class activities and educational videos for the St. Vincent de Paul class. But in addition to learning the science, they had to contemplate how to best present their lessons without scaring or confusing the kids — or without isolating any kids who may have family members abusing substances, or who may have already dabbled in nicotine and alcohol themselves.

“With the sixth-graders, you share what you need to, and you also don’t want to share too much to overwhelm them, because chemistry already is very new to them,” said Kelsey Trulik ’18, a neuroscience major from Ann Arbor, Michigan. “Throwing these big words on them would just be another very scary thing to them.”

Their examination of substance abuse trends in Knox County also spurred some students to reconsider how they originally had planned to package their lesson plans and their videos. The team of students working on a video about nicotine shifted its focus from cigarettes to include chew and dip — common forms of tobacco ingestion in Knox County — as well as e-cigarettes and vape pens, vehicles of nicotine consumption that are growing in popularity.

After mastering the scientific aspects of the videos, Hemkin’s class faced a more technical difficulty: They lacked experience both in front of and behind the camera. To overcome this hurdle, they turned to the Department of Dance, Drama and Film, and Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Uma Vangal, to help act out their video scripts and produce the videos. The nicotine team planned a cartoon-style video, where various characters, storyboarded on a whiteboard, would observe the ingestion of nicotine through cigarettes, vape pens and other methods, all the while contemplating the molecules’ fraught journeys through the body. The team of students focused on ethanol consumption cooked up a skit involving a scientist chatting up a friend at a party, helping the friend to navigate the bodily effects of the contents of their cup.

Interaction with students from Tharp’s sixth-grade science class helped inform the video creation process for Hemkin’s students. Throughout the semester, Hemkin’s class visited the school to present their ideas and workshop hands-on activities with the kids to demonstrate molecular structures and show how they engage with the body. Evidence of the collaboration ran rampant throughout Tharp’s classroom; posters adorned the walls proclaiming atoms to be “building blocks” and chemical bonds to be like “friends holding hands.” Nametags for Tharp’s students rested on her desk, ready to be deployed when Hemkin’s class visited. (Hemkin crafted the nametags herself, incorporating elements from the periodic table to spell each child’s name.)

“I shared with [Hemkin], the more hands-on activities they can do, the better it’s going to be,” Tharp said about guiding Hemkin’s students in their lessons for the sixth-graders. “They have been great, bringing in molecule models and all kinds of things for them to do.”

The evidence-based style of learning that the educational modules embrace is part of a growing push, Phillips said, among drug- and alcohol-educators to provide students with facts, not just scare tactics, about various substances. Hemkin and her students hope that their fact-based videos and activities will help students become lifelong informed consumers about whatever they choose to ingest.

“At the end of the video, it should leave them almost with the thought of, ‘OK, now that I understand what’s happening [in my body], do I really want that to happen?’” Bouquot said. “It’s much easier to comprehend why you shouldn’t do something if you can understand it than if someone just tells you not to do something.”

As a new school year approaches, Hemkin already is thinking about varied applications for the program — different molecules they could feature, different grade levels they could target, different ways she could involve other science students at Kenyon. Though last fall’s videos focused heavily on alcohol and nicotine, substances easily and commonly obtained by middle-school students, Hemkin has her sights set on a broader issue sweeping across Ohio: the opioid epidemic.

From 2011–2016, Knox County averaged 8.5 deaths from accidental drug overdose per year, according to data reported by the Ohio Department of Health. The Mount Vernon News reported in January that 15 residents of Knox County fatally overdosed in 2017.

Sixth-grade students, Hemkin noted, probably aren’t addicted to opioids. But they may know someone who is — a parent, a sibling, a cousin, a neighbor — and shifting their mental approach to substance abuse at an early age, to focus scientifically on the molecular effects of drugs, may inform their decisions and choices throughout their lives.

“If they’re given the opportunity to take an opioid, whether it’s from their doctor or whether it’s from somebody else, they might think more about having a conversation with a doctor to understand why the medication is needed and what it would do to their body,” Hemkin said. The results of the class’s efficacy might be seen as early as 2019, when the sixth-graders, who will then be eighth-graders, will again fill out the biennial Pride Survey on their drug and alcohol use. As the Pride Survey results are released, they may guide Hemkin as she considers additional educational modules on various substances.

“I’m hoping that this will at least be a place to start,” Hemkin said.

While working with the sixth-graders at the St. Vincent de Paul School, Hemkin and her students used hands-on activities to reinforce lessons about various molecules and their effects on the body. In one activity, they used eggs to show the delicacy of a developing brain and the harm that could occur by consuming alcohol and nicotine while a teenager. Students dropped raw and hard-boiled eggs to demonstrate the difference in damage sustained by substance abuse in a developing teenage body (the raw egg) versus an adult body (the hard-boiled egg). “Before and during the egg drop, my students discussed the fragility of the brain,” Hemkin said. “And, the middle schoolers had a lot of fun dropping the eggs, so hopefully that will make the ideas implant more strongly.”

Hemkin’s students used a baseball and a baseball mitt to illustrate how a molecule such as sucrose, or sugar, fits into a taste receptor. They then gave the sixth-graders both regular and sour Skittles and asked if they expected the sour taste to originate from the sweet taste receptors on their tongues. The students compared the molecular structures of sucrose and citric acid, a key sour ingredient, and considered how the structural differences in the molecules could cause them to bind to different taste receptors.

What’s the effect of one glass of wine on someone’s mental and physical capacity, versus three, or five? To help illustrate difficulties encountered through increased alcohol consumption, a Kenyon student attempted to juggle in front of the sixth-graders while simultaneously spelling the word “carbon.” With each additional “drink,” the student picked up one more object to juggle. The student’s ability to quickly spell carbon and juggle disintegrated with each new object in the air.

What’s the effect of one glass of wine on someone’s mental and physical capacity, versus three, or five? To help illustrate difficulties encountered through increased alcohol consumption, a Kenyon student attempted to juggle in front of the sixth-graders while simultaneously spelling the word “carbon.” With each additional “drink,” the student picked up one more object to juggle. The student’s ability to quickly spell carbon and juggle disintegrated with each new object in the air.

When someone first experiences nicotine, they are hit with a pleasant sensation. But the more people use nicotine, the more exposure it takes to experience that same buzz. To illustrate this diminishing return, Hemkin’s students deployed Skittles as a stand-in for the dopamine that is released in the body when nicotine molecules enter the brain. The sixth-graders picked up a model of a nicotine molecule to signal a first smoke” and received four Skittles as a reward. When the molecule model was picked up a second time for a “second smoke,” the sixth-graders could receive only three Skittles. Picking up the model yet again for a “third smoke” yielded only a two-Skittle reward for the students.

When someone first experiences nicotine, they are hit with a pleasant sensation. But the more people use nicotine, the more exposure it takes to experience that same buzz. To illustrate this diminishing return, Hemkin’s students deployed Skittles as a stand-in for the dopamine that is released in the body when nicotine molecules enter the brain. The sixth-graders picked up a model of a nicotine molecule to signal a first smoke” and received four Skittles as a reward. When the molecule model was picked up a second time for a “second smoke,” the sixth-graders could receive only three Skittles. Picking up the model yet again for a “third smoke” yielded only a two-Skittle reward for the students.

Illustrations by Megan Llewellyn ’12.

How Margaret Willison '07 turned her love of pop culture into a mini media empire.

Read The StoryKenyon alumni from different disciplines explain how long-term stress takes a toll on our health — and how we…

Read The Story